The year 1971 was a tumultuous one. Think Pentagon Papers. The 26th Amendment. The Vietnam War. Student uprisings and resistance rallies disrupted college campuses across the country. At the State University of New York at Buffalo, a few years before, a group of students protesting the war had been violently arrested after they sought refuge in a nearby church. The “Buffalo Nine” — as they were named — became a flashpoint on campus, and UB was “torn asunder in violent dispute,” wrote Ann Whitcher-Gentzke in “A Stormy Spring” (UB Today, Winter 2005).

Into this setting of chaos and countercultural ferment, stepped a young Chasidic couple from Crown Heights, Brooklyn, whose Yiddish was better than their English. The rabbi and his wife, Miriam, had been sent by the Lubavitcher Rebbe to open one of the first Chabad centers in the world, at SUNY Buffalo.

Idealistic and perhaps a bit naive, on his first day on campus the rabbi approached a student and asked if he was Jewish. “What difference does that make?” the irate student retorted as he walked off.

It was not the welcome Rabbi Nosson Gurary had anticipated. “It was so upsetting, I said, ‘this isn’t for me.’”

A year later, when Gurary met then-student Howard Mischel, he’d honed his approach. Mischel recalls, “I was walking down the stairs outside the student union building when I saw Rabbi Gurary loitering, looking for Jews. He turned toward me and yelled out, ‘You’re Jewish!’ I couldn’t help but laugh.”

Gurary pulled him into a sukkah “the size of a shower-stall, being towed by a tiny Toyota,” where he recited the blessing on the lulav and etrog. “I was so taken by his style, by the way he could just approach me like that, talking about my Judaism in Buffalo, a really non-Jewish place,” Mischel says. “He was genuine, sweet, kind, and non-judgemental to us kids doing the crazy things we did as hippies. It was a rare quality and that’s what attracted us all.”

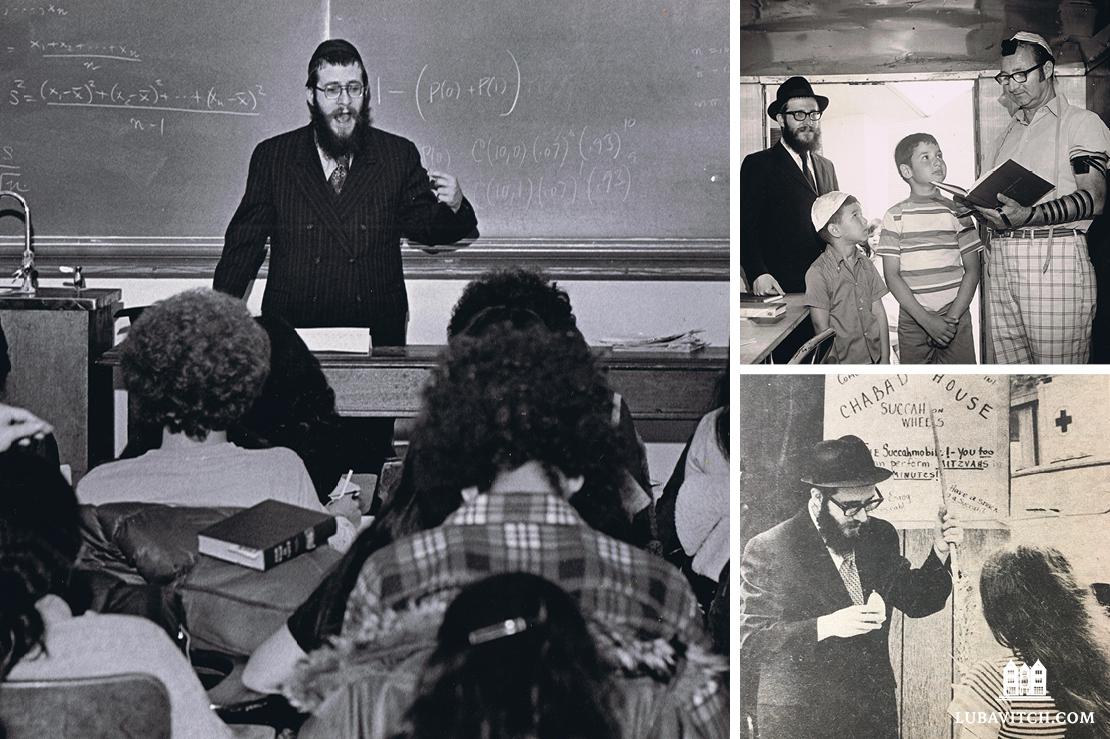

Other students were drawn in by Gurary’s provocative punning. “We had a table at the student union, among the alcohol, drugs, smoke, beating drums, and religious chanting,” says Gurary. The rabbi posted huge signs: ‘POT (Put On Tefillin) HERE’ or ‘LSD – Let’s Start Davening,’ with Chasidic songs blasting from a record player. “I had to catch their attention,” he explains.

The overt display of Judaism triggered some students. “They’d run so fast to get away from me,” says Gurary. But he took those reactions in stride. “I was just trying to make them feel their Judaism, to touch their neshamah in some way. Maybe even make them feel a little responsible so they’d take a moment to think about their identity. And most of those kids who ran away ended up coming back to learn more.”

Gurary is nostalgic about those heady days when it was easier to engage Jewish students. “There was a movement of searching. They cared. Everyone was looking for meaning in life and they were passionately fighting for all sorts of causes.” Today, he says, the students are more fragile. “They’ve got a different set of challenges and needs. They have a lot of stress, and they need warmth and love.”

Susan (Shaina Sara) Handelman, professor emerita of English literature at Bar Ilan University in Israel, encountered Chabad at UB in 1975 while pursuing her Ph.D. Religiously skeptical but curious, she stepped into the pagoda-style Chabad House on Main Street, formerly a Chinese restaurant, one Friday night. Gurary greeted her with his characteristic warmth and asked, “What’s your Hebrew name?”

The question was one of Gurary’s signature opening lines. “When you call a person by their Jewish name,” he explains, “you are touching their essence, their soul. You already have a foot in the door.”

Students recall Gurary’s laughter, which had the effect of turning difficult moments around. “He saw humor where it wasn’t obvious. He had this ability to make us laugh.”

Chaim Mischel, UB 1972

Handelman remembers herself back at UB in 1975: “I was studying literary theory and we all — students and professors — were taking ourselves overly seriously, as often happens in academia. But here was a rabbi, easygoing, comfortable with himself, with lightness and humor in the midst of his profound discussions of the depths of Torah, and in spite of all of the obstacles he faced in his shlichut. When you were with him, you were in another, wonderful world. A magical world.”

Students recall Gurary’s laughter, which had the effect of turning difficult moments around. He saw humor where it wasn’t obvious,” Mischel says. “He had this ability to make us laugh.”

Bridging the Distance

Gurary probably made the faculty laugh as well. In the mid-seventies, SUNY Buffalo branched out to a massive property surrounded by a beautiful lake on the outskirts of town. “The Chabad House was directly across the street from the original South Campus, but now the center of the university was at the North Campus and we were nowhere near it,” says Gurary. “We eventually purchased a building adjacent to the new campus but it was completely cut off by the lake. We were so close yet so far.”

So the rabbi did what seemed logical to him. He constructed a pontoon bridge with pieces of wood floating on big drums, leading from the new Chabad House directly to the campus. “It was a perfect solution. People once again started coming for events, programs and services.”

The pontoon bridge didn’t last long. A fisherman rowing his boat through the lake on Yom Kippur was blocked off by the contraption, and registered a complaint with the university and the city’s Office of Conservation. Chabad found itself at the center of a heated, city-wide controversy.

“Chabad Went One Bridge Too Far,” screamed local headlines. Politicians and pundits blasted Chabad for installing the bridge without permission and demanded that the bridge be removed.

It took a year to work out the legalities, but, undeterred, Gurary secured permission to build a permanent bridge. With the required zoning permits in hand, he hired a company to design and build a bridge high enough and sturdy enough that boats could pass under. “It was a very expensive project and I knew we couldn’t afford it,” he remembers. “But we had no choice. We weren’t closing up shop. I directed the company to bill me monthly with no idea where I was getting the funds.”

As the bills piled up, it occurred to Gurary that the university should really be paying for the bridge. The speaker of the state assembly in Albany, a friend of Chabad, began lobbying the state to fund the project. Eventually, they did.

Today, the strong, beautiful bridge connects Chabad with the UB campus. The university paved the road leading to the bridge and installed an official sign directing students to the Chabad center. “It was a miracle,” says Gurary.

“I found myself sitting before a strange looking man with a black hat, black beard, and black suit. Rabbi Gurary started teaching Judaism 101 in a way I had never learned before. I was blown away. And not only did he teach it, I saw him actually live the lifestyle he talked about.”

Malka Werde, UB 1972

Judaism 101

Early on, Gurary began giving accredited classes in Jewish Studies at the university. “I never thought of doing that,” he says. “It was the Lubavitcher Rebbe who actually suggested and encouraged it.” Lacking a formal degree, Gurary didn’t think it was even possible. But if the Rebbe suggested it, it was going to be done.

Gurary approached the administration, and they accepted his rabbinic studies and credentials as equivalent to an M.A. “I started teaching three courses every semester, and eventually got my Ph.D,” he says. According to alumnus Yaakov Horowitz, who joined the community a few years after the Gurarys came to Buffalo, “He may have finally learned proper English, but the word ‘no’ never made it into his vocabulary.”

Subjects like Talmud, Maimonides, ethics, feminism, and philosophy attracted many students. And if at first they came to accrue credits, they eventually came to nourish their souls. Over the years, Gurary taught 120 different courses in many different departments, including the law school, over 150 students each semester. “I presented Judaism as something real, more than just a lavish bar mitzvah party. They submitted papers and took midterms and finals.”

These classes were often life-changing. Malka Werde (then Michele Braunstein) grew up in Long Island, where her mother instilled her and her sister with a strong Jewish identity but little religious education. “Spirituality was never talked about. I never thought deeply about life.”

Then came the Vietnam War, “and we kids wanted to give peace a chance,” says Werde. When the Ohio National Guard opened fire on a crowd of student protestors at Kent State University, killing four, Malka started questioning, “for the first time, what life is about.”

So, like many others, she dropped out of college at UB and went on a journey to find out. Werde left New York in the summer of 1970 and ended up in the Himalayan foothills of Rishikesh, India, considered a holy site in Hinduism.

After spending some time learning different philosophies and religions, Werde got homesick: “I realized that if I was meant to be Hindu or Buddhist I would have been born in East Asia. But I was not. I realized I was born a Jew and it must be significant.”

She managed to reinstate herself at UB for the fall semester of 1971. Glancing through the course catalogue, she saw “Indian Mysticism” under the Religious Studies program. “I was excited to learn more about it so I decided to take the class. But then, right underneath, I read ‘Jewish Mysticism,’ and I thought, this is really what I need to learn.”

She went to the class. “I found myself sitting before a strange looking man with a black hat, black beard, and black suit. Rabbi Gurary started teaching Judaism 101 in a way I had never learned before. I was blown away. And not only did he teach it, I saw him actually live the lifestyle he talked about.”

Students would argue with Rabbi Gurary, trying to better understand the concepts he was teaching. “The rabbi had answers to questions we kids had,” Mischel offers. “He had such cogent arguments that we were taken aback at times, and had to really rethink our position. And if you didn’t have a strong Jewish education beforehand, it filled a big gap.”

The rabbi always invited his students back to the Chabad House for events. “I had never seen such joy,” recalls Werde. “I had always thought Judaism was so serious. Here they were singing and dancing.” She finally found what she was looking for. “Right in my own backyard.”

Never Alone

It wasn’t all smooth going for the Gurarys. Though Susan Handelman is quick to point out that the students never saw it, making the monthly budget was a dire struggle. Antisemitic incidents were a regular occurance. They felt isolated, living so far from their family and community — their children had to leave home to study in Jewish schools at an early age. It was difficult living a life no one else around them was living.

The hardest, recalls Gurary, was Shabbat morning.

“We’d have massive crowds for Friday night dinners. But nobody was interested in prayers on a Saturday morning. Week after week, I’d schlep all over the eerily silent campus to the dorms where the students were sleeping off their weekend escapades, hung over from the night before. I’d wake them, and beg them to leave their warm beds to join me for prayers so we could have a minyan and read the Torah. When I finally managed to send ten guys to the Chabad center, I’d come back to find half had disappeared. It was humiliating. I thought, ‘how much longer would I have to do this?’”

Gurary had grown up in the cradle of an observant Jewish community where Shabbat services were held in the company of the Rebbe and thousands of energetic Chasidim. He was used to hours of song, learning, and deep discussion that followed prayers together with his homegrown Chasidic friends. These scraped-together minyans of hung-over kids were, frankly, depressing, he admits.

He told all this to the Rebbe, describing the loneliness he felt. The Rebbe reminded him that he was doing G-d’s work. “I am with you,” he said to Gurary.

Decades later, Gurary still gets emotional remembering those words.

“It felt so comforting to know that we weren’t alone. We had the Rebbe himself at our side, and that knowledge really helped us push through.”

Many of those young men that Gurary pulled out of their warm beds are now living observant lives as parents and grandparents of large Jewish families. “Those days weren’t easy, but the rewards bring me joy.”

Remembering Miriam

As the university grew, so did Chabad. New Chabad Houses sprung up in nearby campuses in Rochester, Syracuse, Ithaca, and Binghamton. In 1994, Gurary’s son, Rabbi Avrohom Gurary and his wife, Chani, joined the Gurarys at Chabad of UB. Later, in 1999, came another of Gurary’s sons, Rabbi Moshe, and his wife, Rivka.

In 2006, the UB Jewish community was grief stricken. Miriam Gurary, matriarch of Chabad at UB, passed away at the age of fifty-five after an illness. Thousands of alumni speak of her influence on them. “We felt like this young woman was raising her own children and us students at the same time,” says alumna Chana Pesha Miller Jacobson.

“We laughed a lot at the reunion, sharing stories of our adventures with him and each other in those years. He gave himself entirely over to us in dedication and love and we, in turn, loved him back. And still do.”

Susan Handelman, UB 1975

“My wife had no formal Jewish education and Miriam taught her,” says Mischel. “She opened so many doors to a path of learning and experiencing a deeper Judaism.”

Gittel Lazerson stayed at the Gurarys’ home while dating her future husband, David, after the two were introduced by Rabbi Gurary. “Miriam really took me under her wing,” she says. “I had no idea what traditional Jewish dating was like and she walked me through the whole journey. I even borrowed clothes from her to wear on our first date.”

She credits her decades-long career in education to Miriam. Then the devoted principal and teacher in Chabad’s recently opened day school for the broader Buffalo community, Miriam had asked Gittel if she would take the position of preschool teacher. “I knew nothing about education,” Gittel says. “I wasn’t even sure I was interested in it. But she guided me, and I was inspired by her model.”

Miriam’s perspective was much like her husband’s. “She was always smiling, like she was about to laugh,” says Lazerson.

“We loved her,” says Mischel.

Reunion

Susan Handelman went on to develop a deep connection to Judaism, Chabad, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe. “With the perspective of fifty years and all that’s occurred since then, I am in awe of how Rabbi Gurary’s impact was like a nuclear reaction,” she says, recalling the Rebbe’s description of what happens when a minor interaction between two people catalyzes unpredicted consequences in their lives.

Ahead of Chabad of UB’s fiftieth anniversary, Rabbi Gurary and his two sons — now themselves emissaries at UB with their wives and children — traveled back in time. “We wondered what had happened to all those students who’d been part of the Chabad community,” says Rabbi Moshe. “We’ve remained in contact with so many, but there’s many more with whom we’ve lost touch.”

The Gurary’s eldest daughter, Chani Kozliner, now living in Crown Heights but still very much a part of the UB community, began tracking down alumni. She gathered numbers and made call after call.

This past August, four hundred UB alumni, supporters, friends and their families reunited over Zoom with their college rabbis and rebbetzins. Many of the participants are now living in Israel and woke up at four in the morning to join the reunion.

“It’s special to connect with the old chevrah,” says Mischel. Their lives, like his, look very different from when they first walked into UB as freshmen. Today, Howard (now Chaim) and his wife, Tamar, live in Israel as well. Their two sons and two sons-in-law are all rabbis. “It’s beautiful to see the direction our family has taken,” he says. When their elder son, Rabbi Judah Mischel, published his book Baderech: Along The Path of Teshuvah, he sent a copy to Rabbi Gurary. “Seeing a photo of Rabbi Gurary holding my son’s book was very special. We’ve come full circle,” says the senior Mischel.

Malka Werde is now a Chabad emissary to the Fashion Institute of Technology in Manhattan under the auspices of Chabad of Midtown. Rabbi Nosson Gurary introduced her to her husband, Yakov, in 1975 and married them on the UB campus in the first Chasidic wedding in Buffalo. “Had the Rebbe not sent the Gurarys to UB fifty years ago, I’d have had a very different experience,” says Malka. “I don’t know where I would be in this world today.”

At the jubilee celebration, the alumni spontaneously decided to start a weekly online class led by Gurary who now resides in Monsey, NY. “We didn’t want this special reunion to be a one-time thing,” says alumnus Rabbi Mordechai Siev (a.k.a. Big Mo). “The light of Chabad of Buffalo continues to shine and only gets stronger.”

And so does the laughter. “We laughed a lot at the reunion, sharing stories of our adventures with him and each other in those years,” says Handelman. “He gave himself entirely over to us in dedication and love, and we, in turn, loved him back. And still do.”

She considers Gurary’s humor a spiritual expression. “It’s a kind of a ‘messianic consciousness’ as the Psalms say (126:2) about the era of redemption: ‘Then will our mouths be filled with laughter.’ That ability to laugh comes from a place of deep humility, courage, and faith: the conviction that whatever the surrounding darkness or pain, there is meaning, redemption, and triumph somewhere at the end.”

This article appeared in the Winter 2022 issue of the Lubavitch International magazine. To download the full magazine and to gain access to previous issues please click here.

Tuvia Bolton

Beautiful!!!

Taste of Moshiach….NOW!!

Chaim Mischel

It was truly an honor to be able to participate in the preparation of this article. There are no adequate words to express the gratitude our family feels. Our interaction with the Gurary Family and everyone at Chabad House of Buffalo changed the course of our lives.

Ellen Spund

I transferred to UB at the start of my junior year in 1972. I don’t recall how I managed to enroll in his Judaism 101 class at that time, but Rabbi Gurary made an indelible imprint on my soul. I wish he could know how the spirit never left me, and is now activated at a level I could never imagine. Thank you Rabbi.