Friday, 28 Iyar (corresponding this year to May 22) is celebrated in Israel as Jerusalem Day, commemorating the reunification of Jerusalem following Israel's victory in the 1967 Six-Day-War. Lubavitch.com takes a look at a Jerusalem landmark in the ancient quarter of the holy city.

(lubavitch.com) Visitors to the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City are often moved by the sight of the Hurva Synagogue. Destroyed by the Jordanians in 1948 during Israel’s War for Independence, the synagogue has recently begun construction to restore its former glory.

Just steps away, however, is another shul that is at least as significant to Jerusalem’s history. Less recognized , perhaps, but figuring largely in the history of Jerusalem’s Old City and its reunification after the Six Day War, is Chabad-Lubavitch’s Tzemach-Tzedek Synagogue.

Perched above the ancient Roman market street known as the Cardo, the synagogue, also serving now as a kollel, was the only one found intact following the Six-Day-War. It was here that Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Segal, a dynamic and fearless Chasidic personality, led the first minyan in the Old City following the war.

Though Jews were still reluctant to return to the Old City after its reunification, afraid that Jordanian rule would return, Rabbi Segal led a movement to repopulate the city, and moved into Beit Menachem, otherwise referred to as the Tzemach Tzedek's shul.

Today, it is a thriving hub within the Rova’s [Quarter’s] community, where some 40 young men study daily, and Shabbat services with Chasidim who engage in long hours of contemplative prayer, reflect the authentic character of Chabad of old.

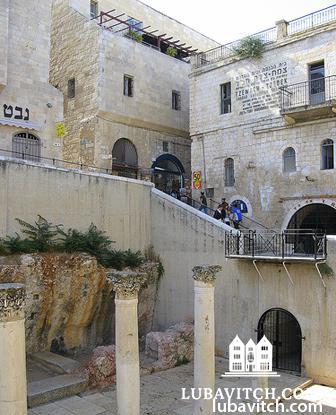

In the Jewish Quarter, Chabad Street runs parallel to the Cardo, about a hundred feet above the famous excavations. Steps connect the street to the main open area of the Rova, with one side overlooking a Roman collonade and the wall of a building lining the other side of the staircase. This is the wall of the Tzemach-Tzedek shul building.

The beginnings of this structure date back to 1847, when after 15 years of difficulties with their Arab neighbors in Hebron, a number of Chabad families moved to Jerusalem and began building their community. The third Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Lubavitch (1789-1865), also known as the Tzemach Tzedek (after the title of his voluminous responsa), encouraged them to build a synagogue. Lacking funds, they reached out to Jewish philanthropists from abroad.

In an 1849 letter to England’s Sir Moses Montefiore, the group wrote, “We have no proper place for prayer and worship, to study Torah. We lack holy books and a proper place to keep them… We have no where to turn, no one to lean on other than the kindness of Hashem, our Father in heaven.”

With funds from Montefiore, Elias David Sassoon in Bombay, and others, the group purchased land for the synagogue in 1850. Finished six years later, the shul was named “Beit Menachem,” in honor of the Rebbe who promoted its founding.

On the east side of Chabad St., just north of the staircase, a plaque on the building wall marks the entrance to Tzemach-Tzedek, and tells part of its history. Passing beneath an archway into a small covered area, to the left one may see a moderately sized room that serves as the “Chabad House,” aimed at reaching out to the surrounding community.

Rabbi Mendel Osdoba has been managing the Chabad House for the last twenty years. Osdoba’s passion for his work becomes clear as he discusses many little details about the synagogue’s history.

“It was Divine Providence,” says Osdoba, when asked how he came to lead this Chabad House. A former student in the kollel at Tzemach-Tzedek, the welcoming rabbi now runs events for the Jews of the Jewish Quarter. Many are geared towards children, and relate to the Jewish holidays. He also teaches informal classes regularly, never asking for contributions from his students.

Through a pair of archways, straight ahead of the entrance to the building, lies a bright open-air courtyard. The ground floor used to house a synagogue as well, and once housed a Sephardic minyan, while the Lubavitch group worshiped upstairs. Today, the small sanctuary is primarily used forchasidic farbrengen gatherings.

A staircase wraps around the sides of the courtyard, rising to the upper floor. The main sanctuary there, used by the synagogue for prayers, also hosts the kollel that meets there daily. Another room alongside is also used by the kollel, and offers dramatic views of the Hurva Synagogue construction. The third large room on this floor houses the library.

Yitzchok Kaufmann is one of the current kollel students. Like so many of the students, the Minnesota native now lives outside of Jerusalem itself. A resident of Beitar Ilit, Kauffman travels about an hour and a half, five days a week, just to study at Tzemach-Tzedek. This, despite there being another Chabad kollel in Beitar Ilit itself.

Though first attracted to the school by the dean, Kaufmann is also motivated by the history of the institution. “It’s the kollel that the [late] Rebbe took interest in personally,” says Kaufmann, a smile spreading behind his short, dark beard.

The shul reflects the tumultuous comings and goings of Jerusalem’s Jews, now chased out, now allowed back, always yearning to return and remain. During World War I, most of the city’s Jews fled to the relative safety of Egypt. Still, one man remained stalwart. A Lubavitch chassid, Avraham Zalman, moved into the synagogue, maintaining its upkeep.

After war’s end, through World War II, few Jews returned to the Old City itself, forsaking it for other neighborhoods outside the historic city walls. But Beit Menachem persevered. During Israel’s 1948 war, however, Jerusalem fell to the Jordanians. The Arabs expelled all Jews from the Old City, leaving Beit Menachem to fend for itself.

In the intervening years, the lower floor had been used for storage, while some type of factory filled the upstairs.

The Tzemach-Tzedek shul has thrived since 1967. These days, one can join morning and afternoon prayers with the kollel students, and full Sabbath services each week. The bright and airy sanctuary on the upper floor brims with a warm hominess and a style of hospitality that connects it to its surrounding community, making it a symbol of continuity in this ancient holy city.

Zalman Nelson contributed to this feature.

Be the first to write a comment.