In 1475, a Jew by the name of Abraham Ben Garton operated a Hebrew printing press in the southern Italian city of Reggio Di Calabria. For reasons lost to history, the press was very short-lived and only managed to print one book, Rashi’s commentary on the Torah. This book, printed on paper made of linen, stands as the earliest printed Jewish book to have its year of production definitively dated.

Only one copy of this book survived into the present day, and two of its pages are currently on display at the Chabad Central Library at 770 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. The Chabad library functions mostly as a research library, where scholars and documentarians can access old and rare books from the library’s 250,000 book and manuscript collection, with some items dating back to the 11th century. The collection is normally stored in a temperature controlled environment, unavailable to the general public.

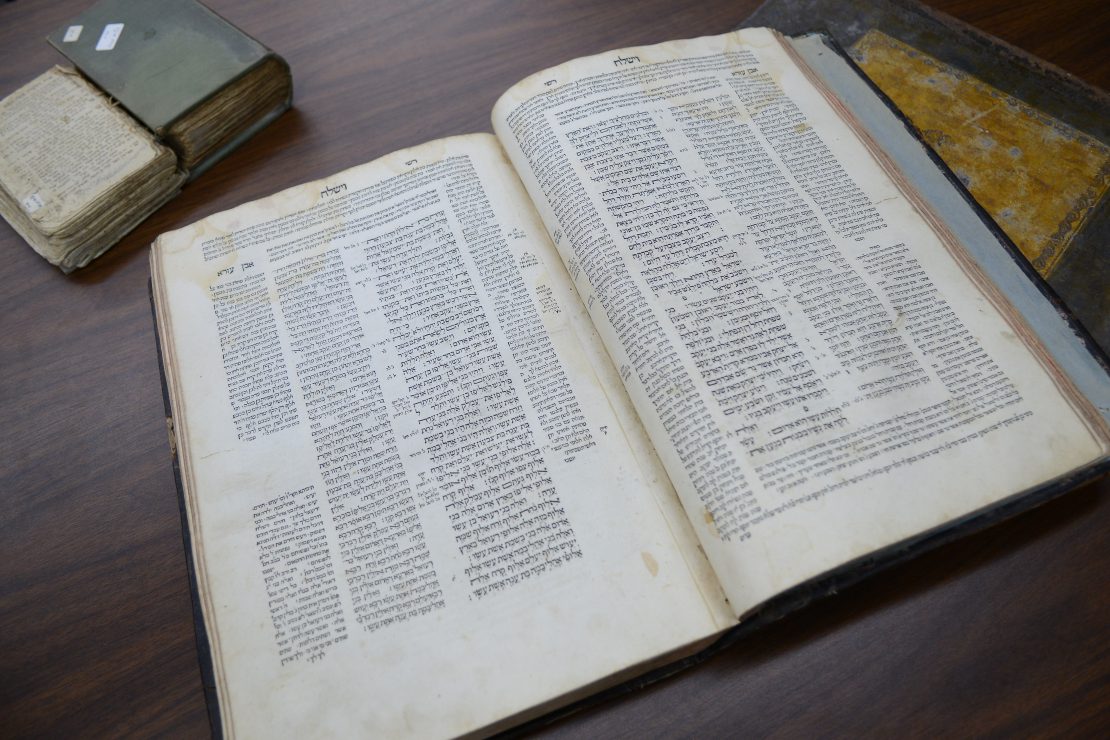

Once a year however, the library runs an exhibition. The current exhibition,“Ginzei Seforim” features a display of rare Jewish books from the first 100 years of the Hebrew printing press and offers a captivating look into a time before the proliferation of books on every possible topic of Jewish interest. Walking from display to display, one gets a real sense of the the evolution of a brand new industry. Hebrew presses went into operation around 20 years after the invention of the modern printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1439. The earliest books did not have their printing dates indicated; the first to be dated was the above mentioned “Calabria Rashi.” This book also gave us “Rashi Script,” so named because that was the print type used; not as is commonly assumed because Rashi himself invented it. In fact Rashi, who lived in France and Germany where the Jews invented a different kind of modified Hebrew script probably never even used the Rashi script which was invented and used by the Jews of Spain as a faster method of writing Hebrew.

This new industry was not warmly welcomed in a world where the Jewish people faced constant persecution and harassment. On display at the exhibit are pages from a Babylonian Talmud printed in 1482 in Guadalajara, Spain. Ten years later, the Jews were expelled from Spain and after that, authorities took to the mass burning of Jewish books. Only small fragments of this Talmud survive. The burning of holy books, particularly the Talmud, which the church considered “hateful to christianity and gentiles” occurred regularly throughout Europe in the Middle Ages. Mass burnings at the direct order of the Pope took place in 1243, 1256, 1316, 1555, 1566 and 1592.

During this dark time, Jews found a few pockets of peace and quiet in Europe. Joshua Solomon Soncino began printing the Talmud in Soncino, Italy in 1483 beginning with tractate Berakhot and completed it in 1484. His printing press would operate for another five relatively undisturbed years and produced more than 20 Jewish works. One example of the Soncino Talmud is on display; in it one can see the first rough draft of our modern layout of a Talmud page with both the Rashi and Tosafot commentary printed alongside the main text. This rough layout would be standardized by the Talmud printed in Venice by Daniel Bomberg in 1520, also here on display. This edition would also establish and standardize the foliation, or page numbers, of the Talmud.

The other items on display are equally fascinating. They include some of the earliest printings of books on Kabbalah, the Shulchan Aruch (Code of Jewish law), Jewish philosophy, and the writings of Maimonides.

The journey some of these books took to get here are almost as interesting as the books themselves. Rabbi Sholom Dovber Levine, the director and curator of the library explained that at the dawn of the modern book industry, there was often a severe lack of materials to use for binding. Bookbinders would buy up bulk scrap paper composed of the pages of old books and use them in the bindings of the new ones; the scrap paper often included the pages of hebrew books which had been confiscated by the church.

Ironically, this practice actually was effective in preserving the pages used, keeping them dry in the wet climate of Europe which contributed to the decay of most of the books printed in that era. Many of the pages on display at the library were found after modern scholars and collectors tore apart the bindings of 16th and 17th books to reveal the historical treasure contained within.

The exhibit will run through at least the end of February, more information is available at ChabadLibrary.org

Be the first to write a comment.