This article went to print last week, and will appear in the forthcoming issue of Lubavitch International Magazine.

On June 24, 2021, at approximately 1:25 am EST, a section of a twelve-story beachfront condominium building in the Miami suburb of Surfside, Florida, collapsed. Rescue operations involved the dangerous work of digging through the rubble in search of survivors. There were none. Nearly 100 people were confirmed to have perished in the disaster. It is one of the deadliest building collapses in American history.

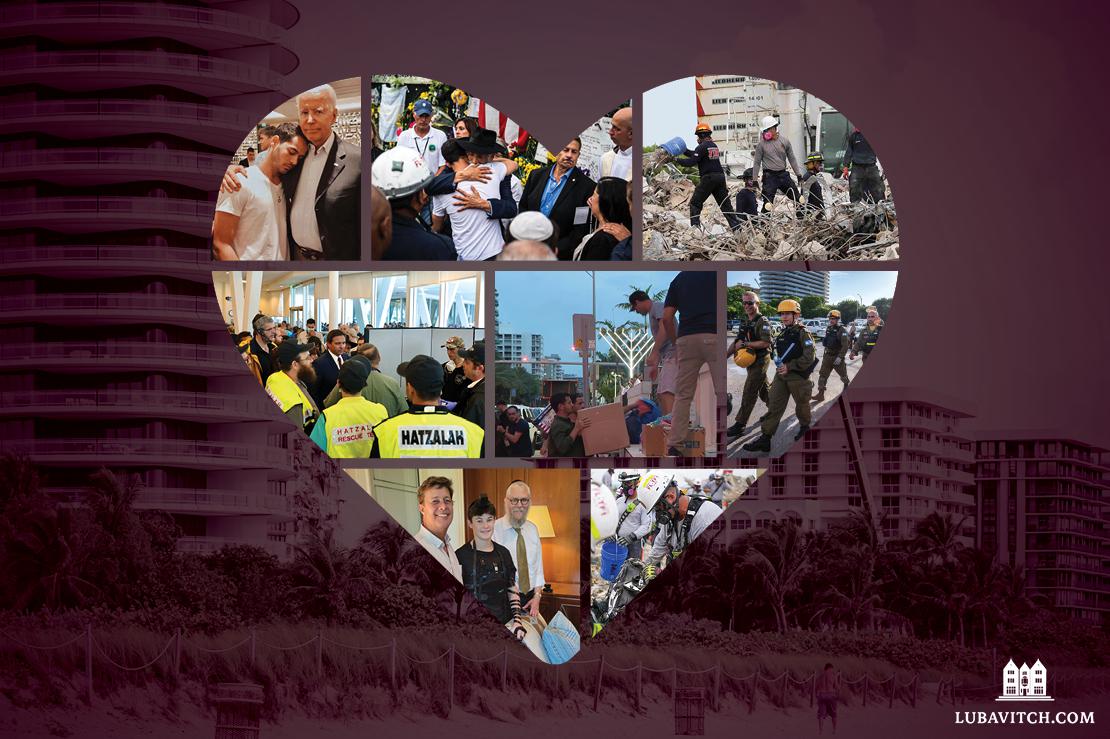

Located in the heart of a thriving South Florida Jewish community, the elegant Champlain Towers South was home to dozens of Jewish families. As city and state first responders began their work, Jewish organizations, including specialized teams from as far away as Israel, arrived at the scene to help. Relatives of those trapped beneath the concrete and steel, desperate for clues of life, prayed and waited in a state of limbo. And when the likelihood of finding anyone alive diminished, family members prayed that the bodies of their loved ones would be recovered.

At the site of the collapse, they clamored for something, some remains of their loved one. “Will I have anything to bury?” asked one desperate father. “A finger, anything?”

“There are certain factors about this event that we just don’t know, and we may never have closure.” It is past midnight when I finally get Rabbi Sholom Ber Lipskar of the Shul of Bal Harbour, on the phone. It has been two weeks since the tragedy, and the 74-year-old has been keeping an exhausting schedule.

His day included three separate visits to congregants who are sitting shiva for family lost in the collapse and meetings with three other families whose relatives’ remains had not yet been found. Rabbi Lipskar has barely slept at all since he was awoken in the middle of the night with the terrible news of the collapse. Champlain Towers — mere minutes from his home and the synagogue he leads — was the address of many of his community members. He describes the aftermath as “a twilight zone.”

“It is as if the affected families are at a battlefront awaiting ultimate judgment about those they love — alive or dead. There are so many levels of pain and emotional turmoil. “For days we hung on to a glimmer of hope as we prayed for a miracle.” The families whose loved ones have been found, he says, found some temporary relief during the shiva period and the rituals of mourning. “But for those that are still waiting, there is no consolation, no closure.”

Baruch Sandhaus, one of the cofounders of Hatzalah of South Florida, has been at “the pile” — the ground zero of the building — daily since the night of the tragedy. Hatzalah emergency personnel respond to the whole gamut of tragedies in their line of work, but nothing could prepare the emergency volunteers for the scene of a building full of residents that fell to the ground in the quiet of night.

For Sandhaus, as for Lipskar and all responders at the site, the pain of coming up short to desperate families starved for information about their loved ones was unbearable. “I didn’t know what to say,” Sandhaus admits when a family member pleaded with him to recover the remains of his loved one.

Recovering the human body as quickly as possible allows mourners to begin to process their grief through Jewish rituals: preparing the body for burial, the funeral, and shiva provide a structure and sequence to grieve in a healthy way.

The Jewish bereavement cycle defines five stages of the mourning process: 1. Aninut, pre-burial mourning; 2. Aveilut, seven days of shiva following the burial, divided into three days of intense mourning followed by four days of mourning and reflection; 3. Shloshim, the 30-day mourning period; 4. Shanah, Kaddish, and other mourning practices from the day of burial through 11 months; 5. Yahrzeit, the anniversary of the day of death. After completing these stages, a mourner is forbidden from continuing their anguish and is encouraged to return to active, even joyous, life.

Each stage requires space and time. The period of Aninut, between death and burial, is characterized by shock, numbness, and disbelief. Our sages instruct, “Do not comfort the mourner during the time that his deceased lies [still unburied] before him.” At this point, the grief is too intense for any effort at consolation. It is a time to simply be with the mourner and offer practical assistance, rather than words of consolation. It is a time of silence, not words.

But the Surfside catastrophe thwarted the routine. Without knowing whether their loved one was still alive beneath the rubble, there was only uncertainty. Families of the missing were unable to enter even the state of Aninut and begin to grieve. Rabbi Lipskar and the South Florida Jewish community fell back on the time-tested tools of community support to bring a small measure of comfort to people suspended between hope and fear.

“The families were inundated with a flood of overwhelming kindness,” says Lipskar. “Whatever they could possibly need was ready and available for them — an abundance of food, clothing, hygiene items, funds to replace lost items, a place to sleep. There was an overflow of volunteers who were there to provide a constant loving presence — a hand to hold and a shoulder to cry on.”

It was an application of the Jewish concept imo anochi batzarah, “I am with you in your suffering,” so that the families would not feel abandoned in the depths of their pain.

Searching For Answers

The search and rescue teams on site of the disaster reported that many of the recovered bodies were difficult or nearly impossible to identify, making it difficult to determine which bodies require a Jewish burial and which do not. According to Lipskar, around 40% of the victims in the tragedy were Jewish.

Dealing with halachic dilemmas he had never faced before in his fifty-two years as a pulpit rabbi, Lipskar reached out to three rabbinic colleagues who had experience with similar issues in tragedies like the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center and the terror attacks that have wracked Israel.

“The families were turning to us with so many questions. When can they start sitting shiva? What do you bury? What happens when there are limbs missing? What do you do if you find more human remains later?” says Lipskar. “We were never trained in these issues. Prior to this week, I had never in my life attended a double funeral. By now I have already attended multiple double funerals. The extent of the devastation is unfathomable.”

One of the key factors needed to begin any mourning process in Jewish law is a confirmation of death. In some missing person situations — a kidnapping or other disappearance — halacha guides families to hold on to hope for a return. But in tragic circumstances, rabbis go out of their way to meet the legal requirements to determine death so that family members can begin grieving and move on.

By Jewish law, death is established by physical evidence, eyewitness testimony of the death, or certain confirmation that the person had been in a situation in which survival was essentially impossible.

In the last scenario, the mourning rituals for the family begin when the family gives up hope of recovering the body. The day of death, or yahrzeit, is noted as the day of the original incident that led to death. If a body or other remains are found at a later date, burial takes place but shiva is not repeated. In a case where there is no body to bury, in most communities, a memorial service of some kind is convened and Kaddish is recited.

Before the modern innovations of forensic science, advanced emergency rescue practices, and global communication technology, in times of war, natural disaster, and the genocide of the Holocaust, rabbis were often unable to declare death conclusively, and families went without ever knowing what happened to their missing loved one.

Thankfully, in today’s information age, instances where families must go through the anguish of waiting to hear about a loved one’s fate are rare.

But there are still exceptional cases and calamities where modern technology is overwhelmed and it simply takes time to determine what happened. In the 9/11 attacks, only fragments of human remains and degraded DNA were left after ground zero had been cleared, resulting in the words of the National Institute of Justice, “the greatest forensic challenge ever undertaken in this country.”

In a contribution to the book Contending with Catastrophe: Jewish Perspectives on September 11th, Michael J. Broyde, professor of law at Emory University, and Yona Reiss, dean at Yeshiva University, explored the halachic implications of the missing dead in the infamous attack. According to Jewish law, a woman cannot remarry unless she has definitive proof of her husband’s death, lest she inadvertently enters into an adulterous relationship.

“In searching for answers, we studied the literature of prior tragedies, finding Jewish legal discussions of husbands who disappeared in the sinking of the Titanic, in the collapse of bridges in Rome, in avalanches in the Alps, in artillery bombardments in World War I, and the sinking of the Israeli submarine Dakar,” they wrote. “We also looked at the cases of Israeli soldiers who had disappeared during the 1973 Yom Kippur War and, of course, at agunah cases related to the Holocaust.”

Using the historical halachic references as a guide, the Beth Din overseeing the 9/11 case declared the victims’ death, enabling their loved ones to mourn those lost and begin rebuilding their shattered lives. “Ultimately, the halachic process provided a time-honored framework for honoring the dignity of those who had died, while creating a sense of direction for the spouses who had loved them,” Broyde and Reiss concluded.

Yet, even with a determination of death and the ability to perform the rituals of shiva, without a physical body to bury, families struggle to find closure.

On August 1, 2014, 23-year-old Lieutenant Hadar Goldin in the Givati Brigade of the IDF was ambushed and killed in a Gaza terror tunnel. Seven years later, Hamas continues to refuse his mother’s pleas for her son’s remains to be returned to her.

Rabbi Menachem Kutner of the Chabad Terror Victims Project in Israel visits Hadar’s mother frequently. “It has been so many years of agony for Hadar’s family, with his body still held by his murderers as a bargaining chip.”

Goldin does have a designated burial spot and tombstone awaiting the return of his body. Currently, his bloodied shirt, recovered from the tunnel, is buried there.

For IDF families in similar situations, there is at least the knowledge that the government of Israel prioritizes respect for the dead and is willing to place significant diplomatic pressure and financial resources to bring closure to its grieving citizens. In 2019, the government secured the return of Zecharia Bowman’s body from Syria thirty-seven years after he was killed and captured in the 1982 Lebanon War. Mrs. Goldin holds on to stories like these as a reminder that there is always hope.

Staying Connected

About three weeks after the initial collapse in Surfside, the victims have been found and identified, allowing the heartbroken families to hold funerals and have laid their loved ones to rest. Any remains that were found and identified were given to families for burial, a form of closure for which they are grateful. In accordance with Jewish law, all identified body parts, even blood and tissue, are collected in preparation for burial.

For the Surfside community, closure will be a slow process. And, as with all traumatic events, the tragedy has forever changed them.

“I have seen my community come together like never before,” says Lipskar. “There is no way to deal with an event of this magnitude intellectually. There are no answers. Logic and even emotions fail us. The only way to process it is by tapping into the spiritual realm.”

Survivors have turned to him in the aftermath of the tragic collapse. “I have found that many have started to relate to the soul in a very practical way. In this event in particular — a convergence of mass and energy — we can see that nothing really gets lost in the universe. There is always a transfer from mass to energy, a life source that continues to flow.”

“That life source continues to exist eternally beyond the physical limits,” the rabbi continues. “In Judaism, we are not allowed to say a single blessing in vain. And three times a day, in our most sacred prayer of Amidah we stand like angels before G-d and recite the blessing ‘Blessed are You who revives the dead.’ We are believers, the children of believers, and for millennia we have maintained a tradition that we will see our loved ones again.”

For some, it is a comforting concept. But, observed Lipskar, even those who don’t relate to the promise of resurrection take comfort in the idea that the soul lives on eternally.

“When nothing makes sense, and emotions are exploding, it is the spirit — the knowledge of the eternal nature of the soul that brings comfort. From what I have seen, this is what the mourners are holding on to.”

He reflects on the prayer said to mourners during shiva. Hamakom yenachem etchem . . . “May [G-d] the Place, comfort you . . .”

“G-d is called ‘The Place’ because we believe that G-d inhabits the infinite and that our physical world is only one small part of reality. We are telling the bereaved that the departed has moved from one space to another space. The soul continues to exist beyond the physical space that it once occupied.” The bond between those who mourn and those who have died must now find expression differently. On the 9th of the Hebrew month of Av, a day of national Jewish mourning which this year fell on July 18th, the Shul of Bal Harbour gathered community leaders, dignitaries, and affected families and friends for the launching of “Unite With Light For Surfside” — a campaign inspiring random acts of goodness and kindness. It is a Jewish custom to dedicate mitzvahs to the souls of the departed, a way in which the living may sustain their bonds with them by expressing their love spiritually, taking some comfort as they continue to remember.

This article appeared in the Lubavitch International Magazine – Fall 2021 issue. To subscribe and gain access to previous magazines please click here.

Be the first to write a comment.