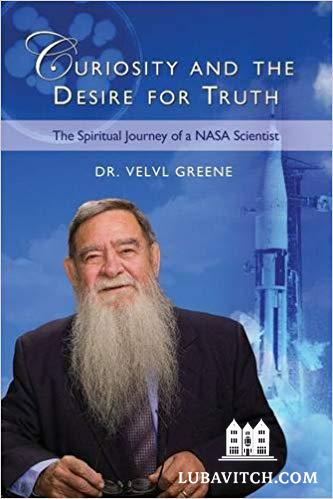

Curiosity and the Desire for Truth: The Spiritual Journey of a NASA Scientist

Velvl Greene, David Greene, Shmuel Greene, and Wendy Bernstein.

215 pages

Arthur Kurzweil Books, 2015.

Something from Nothing

Yaakov Brawer

94 pages

TAV Seminary

Those unfamiliar with Chabad’s philosophy and way of life tend to assume that “those Chabadniks are all alike”—that they all share cookie-cutter opinions and that identifying with Chabad means discarding individuality for the sake of the group.

It is fascinating, in this light, to read read Yaakov Brawer’s and Velvl Greene’s books back-to-back.

Both Brawer and Green are scientists who came to Chabad as adults. Both bring their scientific background to the table as they reflect on how they grapple with truth; both share some of the insights that have been most instrumental to their own thinking; both share their spiritual inspirations and journeys of growth with extraordinary candor.

Yet reading them back-to-back, one finds no overlap. Deeply personal and unstintingly candid, both books provide a window into how one truth can be expressed a thousand different ways.

Judging by Professor Yaakov Brawer’s book, Something from Nothing, he seems to believe that “there is nothing so useful as a good theory.” He is an abstract thinker, distinctly philosophical in his ability to analyze a problem and distill it down to its core components. But he is also able to construct simple analogies that clarify those abstractions. What Pinker does for psycholinguistics and Kahaneman does for behavioral economics, Brawer does for Chasidut—using accessible language to convey subtle abstractions.

Many scientifically-inclined thinkers are frustrated by theological arguments which they believe lack explanatory power. In his title essay, Brawer turns this argument on its head by exploring the difference between “something from something” and “something from nothing”:

Even those who are able to ignore the Creator by claiming He does not exist are stuck with the problem of how and why the universe (including ourselves) came to be. Although there are many approaches to the subject, they all share the common underlying assumption of something from something . . ..The current appearance of any particular aspect of creation is the product of history, or of an evolutionary chain of events that progressively molded a previous something into a contemporary something . . . (p. 16)

It is not easy to understand how a worldview that leads nowhere and ultimately explains nothing became so rooted in the human psyche. The principle of something from something is, after all, the downward spiral of infinite regress. No matter how far you extrapolate back on the chains of cause and effect, there is yet a prior cause which shares the same fundamental limitations as its progeny (i.e. it is defined by physical properties). . .

An objection could be raised. It could be argued that the principle of something from something is by no means a globally accepted axiom. On the contrary, it is rejected by many if not most people, whose concept of reality necessitates the existence of G-d. Many people see an expression of intelligence and purpose in nature . . . (p. 17)

The problem is that, despite the many diverse conceptualizations of G-d, underneath it all, He looks disconcertingly familiar. In fact, he looks, more or less, like us. (p. 18)

In an essay entitled “Reality and Its Shadow,” Brawer explains that the notion that the enamel crystals on the tooth are shaped hexagonally may be wrong. What look like six-sided crystals under an electron microscope are actually two-dimensional shadows projected by the crystals. He illustrates how a three-dimensional rectangular solid projects an image that looks hexagonal. Brawer uses this example to launch a fascinating exploration of how people confuse observation with reality—and the implications this has for the way we understand our physical world.

While Brawer’s book is short, it is thoughtful and compelling, bringing the rigor of the laboratory to his “thought experiments.”

Brawer ends the book with three personal anecdotes. The stories are inspiring in their own right, but they’re also instructional insofar as they show us what it means to live reflectively, seeing each day as an opportunity for learning and growing.

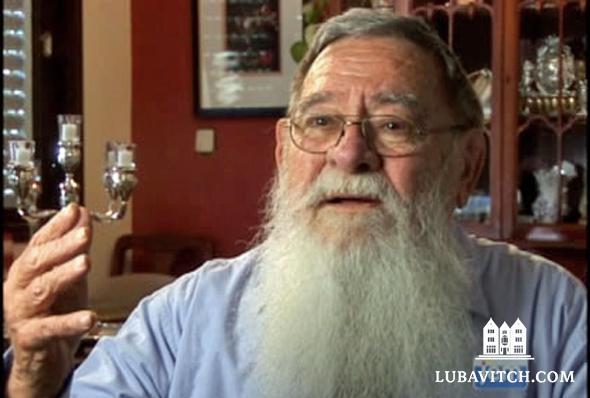

Velvl Greene tells his story (Photo Courtesy of Jewish Educational Media)

Velvl Greene tells his story (Photo Courtesy of Jewish Educational Media)

The late Professor Velvl Greene exemplified a different flavor of scientist, and of Chasid. He did not approach problems with the hairsplitting analysis of the laboratory scientist. He was a microbiologist who used his knowledge to explore the world of space travel. He was able to carefully observe local phenomena with an almost childlike sense of wonder, using his creativity and imagination to explore new possibilities and applications.

At the behest of the Rebbe, he kept journals in which he recorded interesting events and observations that he came across, reflecting on what deeper message might be gleaned. His book, Curiosity and the Desire for Truth, is a collection of some of these observations.

The humility, curiosity, honesty and boldness that made him such an outstanding scientist also colored his journey as a Chasid. In his book, Greene is less interested in being right than in finding truth. He is able to laugh at himself—to accurately remember how he once felt even as he has the courage to grow and change, and to make thoughtful observations that he values for their own sake.

Greene describes the deliberations at NASA about what it might take to send a ship to Alpha Centauri, a star 4.1 light years away. At current speeds of travel, the journey would take 830 years out and 830 years back. But no astronaut could live long enough to survive the trip. The only real solution would be to put men and women together on the ship who would have children who would marry other children. This would go on and on for many generations until they eventually arrived at Alpha Centauri.

“But it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see that this plan presents sociological problems, as well as an engineering issue. How would successive generations of people survive for the 830 years out, and the 830 years back? . . .

Food is an obvious problem . . . Waste was a big issue . . . Other problems abound; If a group of people are confined together for 830 years, how can you make them get along? . . . As our seminar progressed, we discussed all these issues. Then another one popped up that fascinated me: How would the adults teach their children about themselves and their mission?

Think about it . . . for 830 years, all they have is the one instruction manual they started out with. But we know how we feel about old instructions—if an appliance handbook were written in Elizabethan English, we’d ignore it. Junk it! It’s too old to be practical. Even maps—we don’t follow old maps, we correct them!

At the NASA meeting, the professor then made an interesting suggestion. ‘There are few precedents for this kind of situation,’ he said. ‘How does a society pass down its mission and its beliefs to succeeding generations? I think we need to study the Jewish system. So far as I know, they’re the only group of people who for thousands of years, have managed to hand down their traditions intact to each new generation. We should study the Jews, and see how they did it. . . .” (pp. 73-76)

Throughout his journal entries, Greene reveals a deep love of the Jewish people and of the Land of Israel. He has strong opinions, but is willing to change them and able to laugh at himself. His account of buying a hat for his first meeting with the Rebbe is worth the cost of the book itself.

In both of these books, brilliant academics share their thought processes as they grapple with the big questions of life and Judaism, each in their own way. But even more impressive is the window they provide into what it means to live as a Chasid—the ways that esoteric teachings infuse the course of our daily lives with focus, insight, and meaning.

Dr. Yakov Brawer

Dr. Yakov Brawer

Be the first to write a comment.