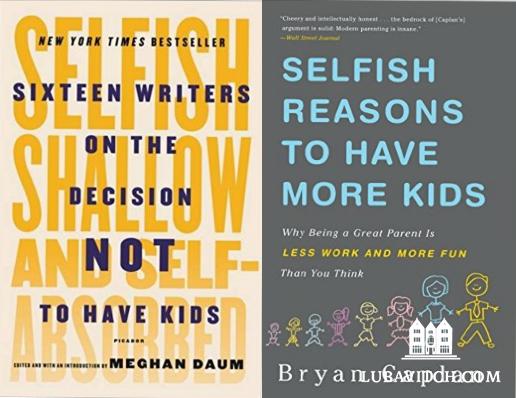

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision to Not Have Kids

Meghan Daum

273 pages

Picador

Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids: Why Being a Great Parent is Less Work and More Fun Than You Think

Bryan Caplan

184 pages

Basic Books

This September, Italy launched its first ever “Fertility Day.” Perhaps it seemed like a good idea at the time, or maybe everyone was in such a frenzy over the fact that Italian women were only having 1.37 kids on average—one of the lowest birthrates in the world—that they didn’t think through the implications of an ad that read, “Beauty has no age limit. Fertility does.” To say that the campaign failed to inspire the average Italian woman is a gross understatement, and it was canceled almost as soon as it had begun. But advertisements like this tell you that we’re in trouble. You hear all sorts of explanations for the declining birth rate: better education, reliable contraception, fewer stable relationships, newer reproductive technologies… But regardless of the global reasons for a lower birth rate, on a personal level, people just seem to want fewer kids. For most people today, having more kids just doesn’t seem to be worth it.

I can’t remember when I concluded that it was “worth it” to have kids. Sure, kids had always featured somewhere in my vaguely planned out future, but the who, what, when, where, and why of it were pretty hazy. The first time I actually considered the great investment involved in raising children was while I was pregnant with my oldest child. Perhaps that was a bit late since at that point it wasn’t really a possibility, more of an inevitability. So I find it hard to claim that I made a carefully calculated choice when it came to the matter of having children.

Today, however, people seem to be calculating this choice more than they ever have before. And like most activities that allow for personal choice, there are elements of both good and bad. On the upside, to choose allows us to more fully appreciate and “own” our decisions, rather than feeling trapped by circumstance. But on the downside, all too often, we end up making the wrong decision.

When it comes to having children, perhaps of the most outspoken group defending their own personal choice is the “childfree by choice” cohort. Meghan Daum recently published a widely acclaimed book, Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision to Not Have Kids, in which she and her fellow writers share their diverse reasons for choosing to remain childless. In Daum’s introduction she states that her hope in writing this book is that people will, “stop mistaking self-knowledge for self-absorption.” The book is meant to shed the childfree individuals of descriptors such as “selfish, shallow, and self-absorbed,” and rather to paint them in a normalizing light as Daum describes them as “thoughtful and uncompromisingly honest.” Proving such a point is not a small undertaking as it goes against the general thinking of most people, and it is one that might well have changed the landscape of thinking on the topic of childfree living, if the authors in the book didn’t come across as so, well, selfish.

When Lionel Shriver writes, “As we age…we are apt to look back on our pasts and question not did I serve family, God, and country, but did I ever get to Cuba, or run a marathon?…We will assess the success of our lives in accordance not with whether they were righteous, but with whether they were interesting and fun.” If that isn’t the prototype for selfishness, I’m not sure what is. Many of the women in this book have undergone one, two or three-plus abortions, many with little expressed regret or afterthought. Laura Kipnis, for example, briefly considered bearing the child that she had conceived, but upon contemplating herself “on a train lugging a baby, a computer (they were a lot heavier in those days), books, and the requisite ton of baby paraphernalia,” it just didn’t seem worth it. So, while Daum may have tried to recast the childfree by choice as not “selfish, shallow and self-absorbed,” but rather “brave and authentic,” they seem to fit the original mold pretty well.

The irony only deepens when it becomes clear that many of the writers in the book aren’t, in fact, childless by choice. While at some point they may have all resigned themselves to the fact that they will not be having children (most, at the time of writing, are over the age of 45), there are those have broken up with potential spouses who didn’t want children, others who have employed various reproductive technologies, and quite a few have desperately longed to have children at some point in their lives. The sad reality is that most of the women (and the authors are mostly women) acknowledge a great love of children and even a desire to desire to have children. And while Daum claims that the authors “bear no worse psychological scars from our own upbringings than most people who have kids,” the vast majority have suffered abuse, neglect, trauma, or all of the above in their own childhood, making the thought of having a child in this fraught with mommy wars, over-critical parenting atmosphere in which we now live, is entirely too much for them to imagine. Though I feel sympathetic towards their struggles, their story of purposeful, joyful, childfree living is unconvincing.

I found Daum’s book overwrought with justifications and profoundly sad, but it was hard to pinpoint objectively what was wrong with its thinking. Because if any one individual has their reasons for not having kids, who’s to say that those reasons are invalid? That was, until I came across Bryan Caplan’s book, Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids: Why Being a Great Parent is Less Work and More Fun Than You Think. Though it was published in 2011, economist Bryan Caplan could have easily been responding directly to Daum’s authors in his thoughtful, grounded, yet lighthearted book aimed at debunking the modern beliefs about childbearing and childrearing.

Caplan counters the claim that being a parent requires decades of sacrifice and unhappiness as fundamentally a seductive political lie. In rejecting this assumption, Caplan argues parents “can sharply improve their lives without hurting their children.” All the suffering parents undergo in pursuit of producing well-balanced, happy, successful children is pretty much wasted, as Caplan illuminates through reference to a multitude of rigorous twin studies done on the topic. When it comes to all the things parents care about in terms of how their children will turn out—character, happiness, financial success, etc.—nurture has little to do with the outcome as long as parents operate within the normal range of behavior. The genes you give your children are pretty important, but after that, most of it’s a wash for ordinarily responsible parents. While this is hard for the tiger moms and helicopter parents to swallow, in the consideration of having more children, it’s actually a win. Because if you don’t need to cart your kid to thirteen different extra-curricular actives to ensure they’ll get into Harvard, then you can really just relax and have a few more kids. The probability that they get into Harvard—and more importantly, their prospects for a successful life—will be largely unaffected by what you do.

Interestingly, Caplan shows that one of the few realms in which parents can actually impact their children in shaping their long-term attitudes is related to the religion with which they affiliate. Studies show that with adopted children and twins living separately, individuals will associate at dramatically higher rates with the parents who raised them as opposed to their biological parents. This is in contrast with nearly every other trait a person possesses.

Caplan also makes the important point that when it comes to the cost-benefit analysis that most people make when having children, their math is quite flawed. Children have high “startup costs,” but the payoff is much more significant down the road. People tend to overvalue the cost of caring for an infant in comparison with the benefit of having an adult child and future grandchildren. So, though waking up with an infant every two hours during the night may seem unbearable now, the time-frame this occupies in the life of a parent is pretty short and the payoff of children later in life is pretty great.

While I found both of these books engaging—Daum’s because it so perfectly characterized the self-obsessed-yet-living-in-self-denial world that we now inhabit, and Caplan’s because it captures the simple, sound truths of childrearing—they both left me with an unanswered question. Why is it that I, and so many women who have come before me, have viewed having children as a natural part of married life without thinking of it as a choice to be carefully weighed and considered? Why do we not feel the need to calculate when it comes to children? Of course, contraception methods were less reliable and available in the past, but even so, if one really didn’t want children, such a reality was (at least partially) avoidable, but for the most part, women let nature run its course.

The answer, I believe, touches on a profound truth, one that while we may be innately aware of, we don’t consciously think about until we are confronted with a situation such as we find ourselves faced with today. When it comes to the materialistic part of who we are, there is a choice. The choice is a simple cost-benefit analysis that we apply to all decisions we make in life. Economists and social scientists, as Caplan reveals, have proven that from this perspective, children are a pretty good choice on the cost-benefit scale. And while there are those who claim they are not having children to “reduce their carbon footprint,” like Sophie Gilbert in Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed, who is of the opinion that “humans are essentially parasites on the face of a perfectly lovely and well-balanced planet,” this claim is essentially false. It is human capital that has produced the wonderful world that we have today. The great economic, social, and political prosperity we enjoy is not thanks to the rainforests we have saved; it’s thanks to human ingenuity. As Caplan puts it, “The main source of progress is new ideas.” While there might be reasons that keep a woman at a given time from having a child, for the world as a whole, as Europe is rapidly realizing, children are good and having more children is a good thing.

However, something powerful happens when we recognize that raising children is something greater than the vehicle to our personal fulfillment and happiness: it is a sacred responsibility. It comes with the recognition that our children are much more than our personal “prize possessions.” Rather, through our actions, we have the ability to allow a soul to reside within a body, to bring a precious life into being. When the question under consideration is whether or not to allow another life to exist on this earth, worrying about temporary physical discomfort or short-term economic hardships is like being worried about the 20 cents you’ll have to pay in gas to drive to pick up your million dollar lottery check; it’s simply not a relevant consideration in light of the “reward.” From this perspective, there is no real choice. Maybe this is the reason—rather than a misogynistic patriarchy— that for centuries, most women have never even asked themselves the question: are children worth it?

The answer is just too obvious.

Be the first to write a comment.