Igrot Kodesh – Vol. 15

Letters of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn of Lubavitch

Publisher: Kehot Publication Society

Format: 6 x 9″, Hardcover, 402pp

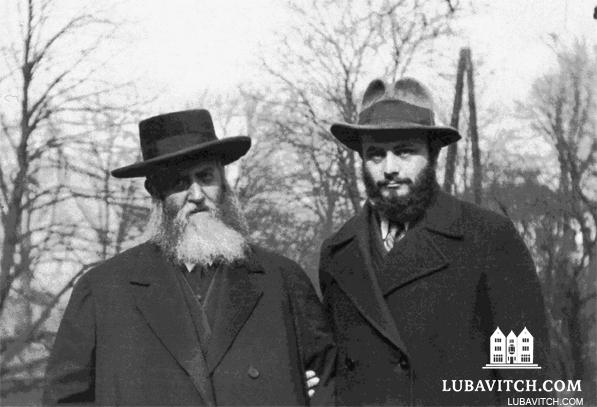

(lubavitch.com) A new volume of letters of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, has been released by the Kehot Publication Society, the Chabad-Lubavitch publishing house. The volume includes 303 letters, many of them published for the first time, documenting the correspondence between Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak and his daughter, Rebbetzin Chaya Moussia, and his son-in-law and future successor, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson. Though the new volume is the 15th in a series of collected letters, its content is uniquely positioned as a stand-alone volume.

Spanning the years 1913-1947 and seven countries, the book provides a rare and intimate look at the personal life of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak and his children. With a recent spurt of interest in the formative years of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, the published correspondence is treasure-trove of primary source material.

Many of the letters are filled with anecdotal conversation, including details of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s trips abroad to Israel, America and Central and Western Europe, and the general comings and goings of the extended family. But certain themes emerge again and again, offering readers insight and perspectives on the relationship between these two leaders of world Jewry.

Early on in the volume, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak concerns himself, as a good father, with the wellbeing of his children and is explicit about his desire for them to maintain close contact with him, even pressuring them to do so. In a Russian language letter to his daughter, written in the winter of 1917, he writes, “A child needs to know that he is the comfort of his parents and their [entire] wealth. . .” Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok writes. By way of a close bond between parent and child, he insists, “the family becomes the most fortunate in the world.”

Through the correspondence between Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak and his daughter, the burgeoning relationship with his son-in-law can be traced. One such example comes after his first extended encounter with his then potential son-in-law in 1923.

Addressing his daughter, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok writes: “This week I thoroughly learned the “laws of Mendel” [a rabbinic idiom referring the character of the Rebbe as a potential suitor]—may he live—almost every day until yesterday evening—for several hours a day. On Sunday the three of us [Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, his son-in-law, Rabbi Shmaryahu Gurary, and the Rebbe] spent the entire day together, and it was very pleasant . . . I can say that I now know him a little better, and the reception has left [us both] pleased.”

In a letter of January 22, 1933, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak extols the virtues of his son-in-law to his daughter. The letter, which concerns the Rebbe’s involvement in the treatment and care for his father-in-law’s ailing health, perhaps foreshadows the qualities the Rebbe would use in his future role at the helm of Chabad’s newly founded educational and humanitarian branches in the coming decade. “Your husband,” writes Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak. “has developed amazing organizational talent—he worries about all of my needs. His attention comes as no surprise to me—but to such an extent it seems [almost] excessive.”

In addition to the growing personal bond between the two, the Rebbe’s reverence for his father-in-law as a spiritual mentor comes to the surface. Despite the physical distance between them—the Rebbe in Wiemar Berlin and interbellum Paris and Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak in the Chasidic courts of Riga, Warsaw or traveling abroad—the Rebbe bares his soul to his own Rebbe.

In a letter dated September 1, 1929, the Rebbe mentions the coming Hebrew month of Elul—the month of spiritual preparation for the coming High Holidays of Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. Turning to his father-in-law and Rebbe for advice, the Rebbe writes, “I am reminded that the month of Elul is rapidly approaching and that it is a month of preparation and repentance [for the new year] etc. What then is the path and the advice, that [the Divine service of Elul] should affect me — that finally a [true] fear of Heaven should touch my heart, so that it be manifest even in the mundane world, [to the point that] even the ‘ego’ should feel this change?”

Other letters shed light on the Rebbe’s pursuit in documenting the history and traditions of Chasidic thought. While the Rebbe’s Reshimot, his personal journal penned in that time period, prominently feature the Rebbe’s meticulous documentation of Chasidic lore and custom, newly published letters reveal the Rebbe’s desire to more deeply probe and understand the “the lifestyle of Chasidut” and the Chasidic thought. In one such letter, of January 21, 1931, the Rebbe explains to his father-in-law his desire for a blessing in “the understanding of Chasidic thought, the materialization of it etc.” Feeling that if he were to “truly want this [level of comprehension] from the depths of his heart,” the Rebbe continues, “it would, through blessing or prayer, be able to affect Above, that all these blessings [for understanding] materialize practically for me.”

While the Rebbe’s involvement in building Chabad’s infrastructure in America has always been clear, his work with Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak while studying in the universities of Berlin and Paris has been shrouded in mystery. The second half of the volume details the Rebbe’s induction into the inner workings of the Chabad leadership.

Between the summers of 1934 and 1935, the Rebbe spent virtually the entire year with his father-in-law. During the spring of 1935, the Rebbe and Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak traveled to Warsaw. Details of the stay can be gleaned from the letters sent by Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak to his daughter, who remained in Paris. A few days before the Rebbe’s return to France, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak sent a letter to his daughter describing a new project he initiated with her husband, the publication of “Hatamim”—a scholarly journal featuring discourses on various Torah subjects and rarely published documents from the archives of the Chabad Rebbes.

Writing to his daughter, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak informed her that while “the editors listed on paper will be others . . . the work itself is [the Rebbe’s]—he is a very, very talented young man . . .”

Over the next four years, the Rebbe annotated and prepared texts for publication in Hatamim, and would be occupied with this until interrupted by the Holocaust. Most of the work would be done via correspondence. Some one hundred published letters documenting his work on Hatamim and later the collected talks and writings of his father-in-law are featured in this volume.

In the year 1936 changes in Polish law made it difficult to transfer money from abroad. As such, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, then residing in Otwock, Poland, transferred control of his funds to his son-in-law in Paris. Moneys from from America, Israel and Europe to support Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s various causes were thus sent to the Rebbe to be used at his father-in-law’s discretion.

The final letters in the volume document the Rebbe and Rebbetzin’s flight from Europe and appointment to the head of Chabad-Lubavitch’s social service and outreach arms.

The book can be purchased online from kehot.com.

Be the first to write a comment.