More than 2.3 million people are behind bars in the United States. About 4,000 of them are Jewish. While Jewish inmates account for only a small fraction of the prison population, the perception that incarceration makes no impact on the Jewish community exacerbates the already difficult experience of those affected.

Family members of incarcerated individuals are sometimes referred to as “hidden victims” who aren’t acknowledged by their own communities. Jewish hidden victims often feel significant shame in discussing their incarceration experiences within their communities. Without a societal safety net or support from mainstream Jewish organizations, Jewish families dealing with incarceration are marginalized. Women and children from these families often face serious psychological and financial risks.

Beginning in the 1970s, the Lubavitcher Rebbe strongly advocated for those affected by incarceration, imploring the Jewish community to better support Jews behind bars. Nearly fifty years later, criminal justice reform is still one of the most pressing issues of our time, affecting thousands of families. Who are these families, and how can the Jewish community better support them?

Aliza C.* balanced her five-month-old on her hip as she ushered her sons—ages three, five, and seven—into her synagogue’s social hall for the community seder. Families gathered around the rows of tables, all of which were set with stacks of matzah and cups of grape juice. Looking around at his friends, all of whom were standing beside their fathers, Yakov, the five-year-old, crossed his arms. “Why isn’t Abba here?” he demanded.

His father, Moshe had been incarcerated four months earlier on charges of theft.

Aliza tried to quiet Yakov discreetly, but his complaints only grew louder.

“My teacher said I’m supposed to ask Abba the Four Questions. Why isn’t he here? Why doesn’t he love us anymore?”

People started staring as his cries escalated in volume. Already embarrassed that the rabbi had sponsored her family’s tickets to the seder, Aliza felt the blood rush to her face. The baby started crying in response to the ruckus. Soon, everyone was looking as Yakov’s outbursts devolved into a full-blown tantrum.

Aliza was distraught. “It was horrible. The worst Passover I ever celebrated. I wanted to curl up in a ball and die.”

It was just one more way life had changed since Moshe was taken away in handcuffs. “Holidays used to be one of my favorite things. Now I dread them,” she said. After all, it doesn’t really feel like the holiday of freedom when your children’s father may be locked up for a minimum of ten to twelve years and then deported.

Families of inmates are an overlooked demographic who often pay high financial and emotional costs for crimes they did not commit. By the time they have experienced the full criminal justice process alongside their loved ones—arrest, pre-trial detention, conviction, jail, probation, imprisonment, and parole—many families are financially and emotionally devastated. For some, life will never return to normal.

For some families, life will never be the same

For some families, life will never be the same

Waiting On The Outside

Rabbi Sholom Ber Lipskar founded the Aleph Institute back in 1981, when the Lubavitcher Rebbe directed him to create a support organization for Jewish inmates and their families. Today, Rabbi Shua Brook serves as the Institute’s Director of Family Services. And according to him, the biggest misconception surrounding incarcerated Jews boils down to money:

“Most people I meet who are unfamiliar with the prison system have this perception that Jews who are in prison must be rich, white-collar criminals,” he says. “Everyone always hears about the famous people who end up in prison. But, in truth, way more than half of the Jewish people in prison—after legal fees and lack of work—leave families behind without the basic means to survive. Not to mention all the emotional baggage that they now need to deal with.”

Helen A. says she was “a Jew who thought Jewish people wouldn’t be in this situation.” The social worker grew up in an established Jewish community and her family lived a normal middle-class lifestyle. Her husband, a war veteran, had long suffered from PTSD and struggled with misuse of painkillers. In October 2015, pain from a recent car accident had exacerbated his use of narcotics. She noticed that her husband became secretive about his comings and goings. One day, she walked into her living room to discover “shady looking characters” sitting on her sofa.

“I had a pit in my stomach. I knew something was wrong.” Three weeks later, her husband was arrested on charges of purchasing stolen goods from an interstate armed burglary ring. The media had a field day.

“I didn’t want to leave my house,” the mother of three recalls. “It was so humiliating. I was paranoid that everybody knew. I started doing my grocery shopping far away from my community so I wouldn’t bump into anyone I know.” Her sixteen-year-old daughter went to school as her classmates read about her father’s court case in the news.

Sheina Elberg, who handles intake at Aleph’s Family Services, recalls the day that Helen reached out to Aleph. “Like so many other families that first experience incarceration, Helen just couldn’t believe that she had someone that was close to her in legal trouble and in prison. The average family members whom we deal with are truly decent people who fell into a situation that they would have never imagined being in if it weren’t their lived reality.”

Helen’s intense feelings of shock, shame, and isolation were compounded by a deep concern for her husband’s future—and her family’s. It was during this period of uncertainty that she connected with Aleph, one of the only support networks for families of Jewish inmates. The rabbis at Aleph helped Helen navigate the American criminal justice system, using their expertise and resources to advocate for her family’s needs.

Aleph connected Helen with a support system and an experienced life coach who helped her adapt to her new reality, re-enter the workforce, and support her children on her own.

“Every family is facing their own unique circumstances, but they all need the same thing: someone who truly cares for them unconditionally, that will be there for them through thick and thin,” says Rabbi Brook.

Holding on

Holding on

The six staff members in Aleph’s Family Services department work around the clock, currently helping 1,450 families deal with their incarcerated relatives.

“When we get in touch with a family, we make their issues ours, whether it’s figuring out how to keep the mortgage afloat now that a breadwinner is behind bars or arranging and subsidizing therapy for the kids,” Brook says.

There is no formal governmental safety net for families who suddenly lose a spouse or parent to the prison system. Brook and his team connect the families with all the available resources, from food pantries to Medicaid. Aleph assists with job placement and reaches out to the local community and to donors, helping spouses form plans to become self-sufficient.

And spouses are not the only family members caught in the crosshairs of incarceration. For elderly parents who rely on their children for physical or financial support, a jail or prison sentence cuts off their primary source of assistance. Aleph works to ensure that these older dependents don’t fall through the cracks.

Rabbi Sharon Weiss, an Aleph caseworker, recalls arranging a driver to help an elderly mother in Florida visit her son in prison. Weiss tried calling the mother multiple times and was unable to reach her. He started worrying for her wellbeing, since she lived alone and her only son was incarcerated. After numerous attempts to reach her failed, Weiss contacted the police to do a safety check on her. Thankfully, she was fine. She had just experienced an electrical outage in her apartment and misplaced her phone. After the police confirmed that she was well, the woman called Aleph in tears. “You are the only ones thinking about me,” she said.

Other parents suddenly find themselves back in the position of caretaker when their children are incarcerated. When Jennifer K.’s 34-year-old son Abe was placed on house arrest, she was appointed his guardian. Like most of her peers, the retired professional had been enjoying her empty nest for years, and she was a very active member of her synagogue. But all that changed when Abe was arrested for his second offense. “Suddenly, my husband and I couldn’t travel anywhere together because someone always had to be home to monitor Abe.” The couple spent tens of thousands of dollars on their son’s legal costs, and now they await his sentencing.

“We know that he brought this on himself, but the prison system is truly terrible,” says Jennifer. “When Abe was transferred to county jail, we did not know where he was for a whole day. When we finally located him, we found that they never provided him with his medication. At the new jail, a group of inmates started threatening him with violence and were extorting him for money.” The terrified mother asked her Aleph contact for help. The rabbis were able to get Abe transferred to another pod away from danger, but he is still kept in a cell twenty-two hours a day for his own protection.

Brook believes that awareness of the dehumanizing realities of the prison system will inspire compassion in most people. “As outside observers, we need to shift our judgement from ‘that guy deserved it’ to one where we see every individual as an imperfect human being and deserving of basic dignity.”

A Jewish inmate prays from a siddur obtained for him by The Aleph Institute

A Jewish inmate prays from a siddur obtained for him by The Aleph Institute

Suffering in Silence

Children whose parents are involved in the criminal justice system are particularly vulnerable to a host of challenges and difficulties: psychological strain, antisocial behavior, suspension or expulsion from school, and economic hardship. They also perpetuate a cycle of crime as they are five to six times more likely than their peers to become entangled in the criminal justice system as adults.

Some of this psychological impact is caused by the social stigma that is part and parcel of having a parent in prison. “The children are innocent. They did nothing wrong,” says Aliza. “Still, people keep their distance from them, and the children end up paying for other people’s mistakes.”

Her youngest was born just a month before her husband was arrested. And, for the first nine months of her husband’s sentence, Aliza barely left her house. With the help of her life coach—paid for by Aleph—Aliza slowly started putting the pieces of her life back together. Now a single mother, she decided to host a Shabbat afternoon gathering for her seven-year-old son’s friends. Aliza set out cookies, juice, and plenty of chairs. No one showed up.

In some ways, Aliza can understand the hesitation. “Naturally people want their kids to be friends with kids who have mainstream homes,” she says. “It is uncomfortable to associate with families who have problems.” But the exclusion results in a revictimization of the children.

Sarah O. is a mother of a teenage daughter and two middle school-aged sons. Just before the 2008 housing crash, her husband unknowingly gave financial backing to a con artist who was defrauding properties. The financial crisis brought the misdoings to light, and, in the ensuing fallout, her husband was sentenced to twenty-five months in state prison.

“We lost everything,” says Sarah. “But since it was a financial crime, people thought we had money. They did not know that my kids were walking a half hour to school because I did not have gas money to drive them.” What was worse was that “everybody and their mother turned against us.”

“My children became invisible to their relatives. We were no longer invited for the holidays.” Her local Chabad stepped in to fill the role of family. “I didn’t have any money to make a bar mitzvah for my middle son,” she recalls. Her Chabad rabbi partnered with the Aleph team to throw the bar mitzvah boy a small celebration. “Even though my husband wasn’t there to take him up to the Torah, I still remember it as an amazing experience.”

Research suggests that the strength or weakness of the parent-child bond and the quality of the child and family’s social support system plays a significant role in a child’s ability to overcome these challenges. “It is critical for us to understand the unique dynamics of each family unit and to try to ensure that the children experience positive environments and maintain the healthy connections they need to succeed in life,” says Rabbi Aaron Lipskar, executive director of the Aleph Institute.

One way Aleph does that is by facilitating a continued relationship between children and their incarcerated parents. Aleph underwrites the travel expenses related to visiting a loved one in prison through their Kahn Visitation Fund, and sends age-appropriate holiday gifts from an anonymous post office box, with notes reading either “love from Daddy” or “love from Mommy.”

“The first Chanukah that my husband was in prison, we got some gifts that said, ‘love Daddy,’” says Sarah, whose husband is now out on parole. “I can’t explain how happy it made my children. They weren’t expensive gifts, but it meant the world that Daddy didn’t forget them.”

It is these efforts to keep those vital family ties intact that makes Aleph “widely known and respected by penal and judicial authorities,” says the Honorable Jack Weinstein, a federal judge in the Eastern District of New York. “Its assistance to defendants and their families provide standards of compassion and aid worthy of emulation. It assists those outside—particularly the children of prisoners—to retain their ties with prisoners.”

From a private event in NY for moms and wives of those incarcerated

From a private event in NY for moms and wives of those incarcerated

A Family Shattered

The physical separation, financial devastation, and emotional turmoil of a spouse or parent in prison often destroys the family unit. The divorce rate among couples where one spouse is incarcerated for one year or more is eighty-nine percent.

Helen is now divorced from her husband. “I knew that I could never regain that trust back. I felt like I was married to two people.” She also does not forgive him for leaving her and the children destitute. “I had to go back to my parents, who are eighty years old, and ask them for money so we wouldn’t be evicted. I can’t even describe the guilt.”

Her Aleph caseworker connected her with a professional marriage therapist who helped Helen navigate the dissolution of the marriage. She still checks in on her ex-husband regularly to make sure he is doing okay in prison, and she wants her children to have relationships with their father.

Aliza says that she sometimes feels that losing her husband to prison might be harder than losing him to illness: “My husband and I were married for seven years. Then, one day, he’s just taken away. There is this torture that he’s alive, but I can’t have any sort of relationship with him.”

Phone calls from prison are limited to fifteen minutes at a time. Every email costs money. Aliza has young children to care for, and her husband is facing over a decade in prison before he’s deported. So she is considering moving overseas to be with her family for support. “My kids don’t see their father anyways. I have only been able to take them to visit twice, and it was a disaster.”

“I have come to the realization that I will be a single mother for a long time,” Aliza says. “I need to put the welfare of my children first.”

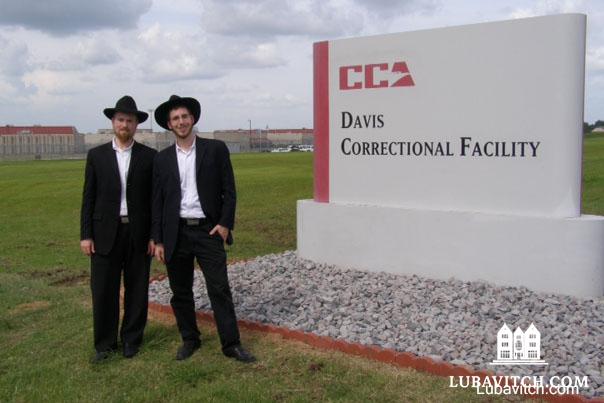

Rabbinical students visit correctional facilities across the country

Rabbinical students visit correctional facilities across the country

She is not sure where her husband fits in to the picture, but says she’s reached the point where she needs to just live her life.

For formerly-functional households like Aliza’s and Helen’s, the impact of incarceration is severe. But for dysfunctional households, the impact of a prison sentence can be catastrophic.

Chloe’s father has been in prison for five years. The teenager lived with her mother until last year, when her mother died of complications related to breast cancer. Aleph arranged a Jewish burial for her mother as well as Kaddish services. As for Chloe, none of her relatives were able to take her in. Aleph had promised Chloe’s mother that they would care for Chloe after her passing. And so had her non-Jewish friend, Yvonne R.

After her mother passed away, Yvonne stepped in to foster Chloe. “Chloe has been through so much trauma,” explains Yvonne. “She lost her mother, she lost her home. Her family gave away their pets. Her father is in prison and does not have a positive relationship with her. Her conversations with him are monitored according to court orders.”

The foster mom, who does not have any children of her own, asked Aleph to help her create a strong support system for Chloe. “It is important to Yvonne that she provides Chloe with a connection to her Jewish faith,” says Aleph caseworker Dina Minkowitz. So Aleph helps Chloe arrange regular visits with local Chabad families for Shabbat and other holidays.

Yvonne says that Chloe naturally gravitates toward the traditions that these families model. “She’s never had proper family structure,” Yvonne says. “So exposure to that positive environment where people really care about her is crucial to her success as an adult.”

In order to offer Chloe more time in these positive environments, Aleph also underwrites Chloe’s enrollment in a Jewish overnight camp every summer.

Summer camp can be a vital outlet for at-risk children to just “feel normal”. This past year, Aleph paid a partial or full scholarship for ninety-seven children to go to Jewish summer camps through their Jonathan Stampler Camp Fund. “Camp takes care of three major aspects,” says Brook. “It gives the parent a break; it gives the children a fun, immersive experience away from the stressors at home; and it instills Jewish values and hope. It is one of our most impactful programs.”

But Aleph often achieves their greatest successes when they can get local communities and charitable organizations involved. “We reach out to community leaders and make them aware of families in their communities who are struggling,” says Brook.

According to Helen, raising this kind of awareness is crucial. Because most people would never guess that families in their communities struggle with incarceration.

“We could be your next door neighbors,” she says.

Be the first to write a comment.