As the iron cell door clanged shut behind her, 37-year-old Marcia Singer* felt herself going numb. Staring down at her prison- issue jumpsuit, she thought of her two young children separated from her by the grey walls that would confine her for the next several years. Her world turned black as she felt herself sinking into the darkness.

Today she shudders when she recalls those first days in the Florida State penitentiary, tormented by thoughts about her children suffering and her helplessness to do anything about it. With their mom locked up, they would go to live with her ex-husband in a single room in the back of a small house that had no air conditioner to relieve them from Florida’s oppressive heat. There’d be no money, and very little food for her children. Her desperation deepened.

Marcia grew up in a middle-class Jewish home, but a proclivity for making ruinous life choices alienated her from the rest of her family. The “bad kid” who dropped out of school in a family where everyone else were doctors, Marcia, whose parents had died some years earlier, was since excluded by relatives from events like the annual Passover Seder. Shunned by family and community she drifted away, eventually marrying a Jamaican man, the father of her two children, 11 and 15 at the time of her incarceration.

The marriage was troubled and ultimately disintegrated. As a single mom living in a crime-ridden neighborhood, Marcia struggled to make ends meet, finally working her way up to become a manager at a large home and garden retailer. In that position, she was authorized to mark down store items on a regular basis. As she tells it, after marking down a certain item that was purchased by a friend, she was accused by store management of colluding with the customer and fired for misconduct. The retail chain filed charges against her.

With no money to hire an attorney, Marcia didn’t stand a chance in court. She accepted a probation plea deal with the court, though she insists that she never acted illegally. Her troubles piled on: a few months later, while still on probation, she agreed to pick up her son’s friend and drive him home. Marcia says she was unaware that she was being used as the getaway car by her young passenger who was on the run after committing a robbery. Once again, she found herself in court, this time charged as an accessory to a crime and in violation of her probation. She was sentenced to three years.

A first time offender navigating the criminal justice system on her own, Marcia desperately tried to find some semblance of familiarity in the cold and unforgiving corrections institution. There was none. Her anxiety about being separated from her children put a crushing weight on her. With no one on the outside to drive her children to the facility during visiting hours, more than a year would pass during which she would not see them. The weekly letters from her 15-year-old daughter, Abigail, who shared her misery compounded Marcia’s suffering.

Judaism Behind Bars

Marcia is one of approximately 4,000 Jewish inmates in the United States, comprising less than 1% of the total prison population. Most of the relatively small demographic is male, and a majority are serving time for white-collar crimes such as fraud and tax evasion. Others got into trouble with the law over drugs or alcohol addiction. Prison life is not easy on Jews seeking to practice; honoring holiday traditions or the ability to participate in Shabbat services will often require working through difficult bureaucracy. Many are serving their time in hostile environments where the Jewish population is usually the smallest denomination and vulnerable to anti-Semitic activity.

Marcia’s lack of affiliation prior to her incarceration is not unusual: many Jewish prisoners have no real connection with a religious community before they get into trouble. Rabbi Benny Lew, who works for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, says that it is natural for inmates to get involved with Judaism in the prison system, where a social structure of racial cliques becomes a survival mechanism.

Many Jews gain a totally new appreciation for their Judaism from a spiritual and communal perspective. “For those who come from traditional Jewish backgrounds it’s a very impoverished Jewish life,” Lew says, “but for others, prison becomes the vehicle through which they practice religious tradition with newfound meaning, like keeping kosher and celebrating holidays.”

Though she never thought much about her faith, Marcia instinctively ticked off “Jewish” on her prison admission form. She was one of eight Jewish inmates out of a total of 755 women when she entered prison. One of her fellow Jewish “girls” serving a life-sentence took Marcia under her wing, showing her the ropes. “Janey’s been there forever and she does a lot in the prison,” Marcia says.

The connection was critical. “Usually you have to get on a waiting list to get into school there, but Janey put me on the top of the waiting list and pushed me to do school.” As more Jews entered the prison during her time—all 17 of them banded together to become a mini-family, helping each other endure the long days, and even longer nights, away from their loved ones.

Soon Marcia signed up for her prison’s kosher food plan and actively sought out opportunities to learn more about her faith. “I was searching for something to hold onto,” she admits. “As an adult, it was the first time I connected with my Judaism.”

Unlike Marcia, Harvey Main had been connected with his local Chabad House, but he never really made space for spirituality. When the now 64-year-old went to prison in 2008, he used the sudden pause in his normal life to introspect, eventually immersing himself in the opportunities for Jewish learning and Jewish services that were offered.

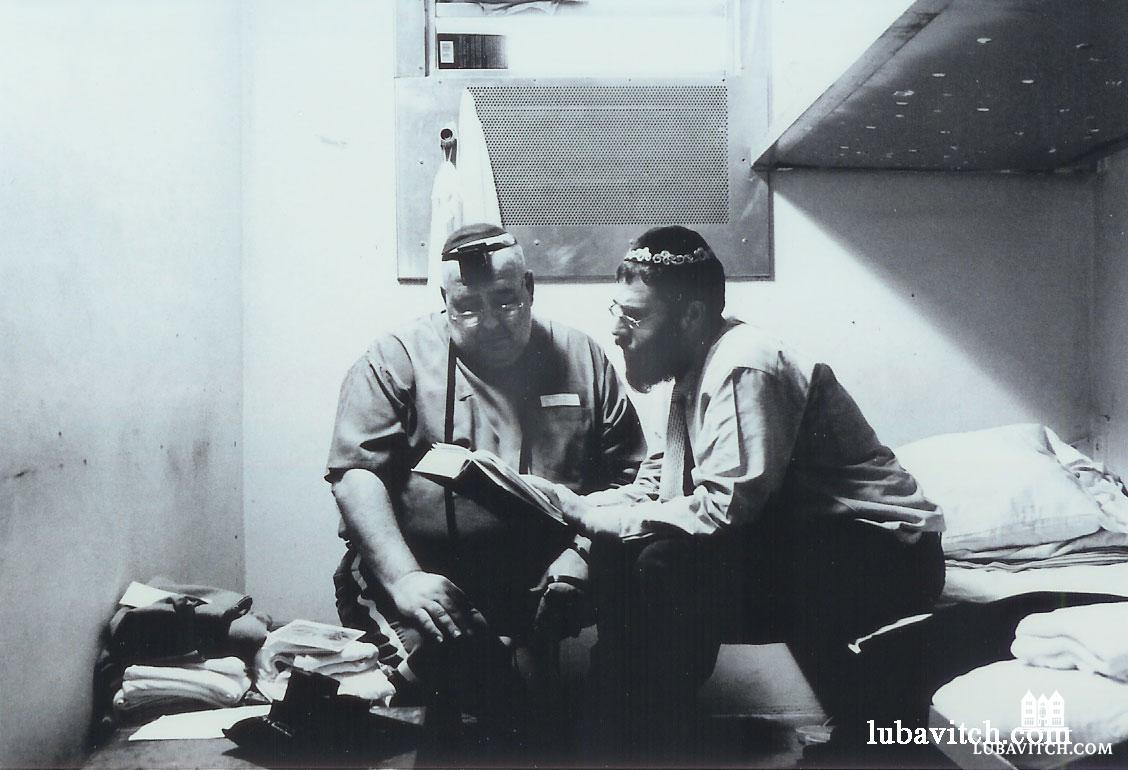

“From the moment I got there, I took upon myself to study and immerse myself in Torah,” he says. As an affiliated Jew, he had some familiarity with his traditions, and chose to use his five-year prison term to expand his knowledge and understanding of his faith. An avid reader, he took advantage of “a very good Jewish library,” studying everything he could to help him become a better person. More than everything, he says, the Jewish camaraderie was critical to him, and he became part of a community with 15-20 of his fellow Jewish inmates giving him some semblance of his former life.

“Being separated from family is the most difficult thing, making the companionship of other guys I learned to count on, and building our own community while we were away from home vital, possibly even transformative.” He remembers one particular holiday in prison, sitting in a Sukkah that Chabad volunteers had built, and celebrating the Jewish holiday surrounded by fellow Jews. “I felt transported out of prison during those moments.”

*Some names and identifying details of the inmates mentioned in this story have been changed to protect their privacy.

“,”

The Rebbe’s View on Prisoners

At 716 per 100,000 of the national population, the incarceration rate in the United States is the highest worldwide, housing 22 percent of the world’s prisoners. Its bloated system has prompted national and state governments to reevaluate. In a push to reform a U.S. criminal justice system that now has 2.2 million people serving time, President Obama became the first sitting President to visit a federal prison in July 2015. In early November, the Justice Department granted 6,000 non-violent offenders an early release from prison—the largest one-time release of federal prisoners ever.

Now an issue at the forefront of the national conversation, “it’s what we’ve been saying for 35 years!” says Chabad emissary Rabbi Mendy Katz. Katz is director of the Florida-based Aleph Institute, a Jewish humanitarian organization that provides critical services to families in crisis. In 1976, the Rebbe began publicly advocating for prisoners, raising awareness of the problems inherent in incarceration from a Torah perspective.

“The Rebbe had a very special place in his heart for the downtrodden. He did not believe in locking people up and just throwing away the key,” says Katz. Many of the Rebbe’s talks decried the practice of depriving prisoners the ability to live productively while serving out their punishment. The Rebbe was emphatic about helping Jewish prisoners precisely because so many of their basic human rights and freedoms had been taken away from them. He called upon Chabad emissaries to do whatever they could to support incarcerated Jews and restore to them their humanity.

Rabbi Yochanan Friedman of S. Cruz, CA, has more than a decade experience serving as a Chabad chaplain. “Any chaplain would agree that revisiting the idea that people have the potential to become better is a step in the right direction,” he says. Writing off an offender as an inherently “bad person” is not, he insists, a moral perspective. “It is not befitting a moral society to be willing to give up on a human being.”

Friedman believes the teachings of the Torah can help a person become healthy and productive with the knowledge that he or she has a vital part to play in the universe—even from the confines of a prison cell. “The idea that every Jew has an inherent bond with the entire Jewish people, with the Torah and with G-d, offers an inmate a glimmer of hope for a better life.” Giving an inmate these faith-based tools can also help prepare him or her for eventual re-entry into society as a law-abiding citizen.

Aleph

Founded in 1981 at the behest of the Rebbe, Aleph Institute addresses the pressing religious, educational, humanitarian and advocacy needs of incarcerated individuals, and implements solutions to significant issues relating to the U.S. criminal justice system, with an emphasis on families and faith-based rehabilitation. Its various programs help Jews observe Jewish holidays and assist them with their daily Jewish practices, books, food items and materials during their prison stay. It also prepares them to reintegrate into society once they are released.

After spending close to a year in the county jail waiting to be sentenced, with still no visits from her children, Marcia finally met Aleph’s director Rabbi Katz during one of his routine monthly visits to the women’s penitentiary. By then Marcia was benefitting from some of Aleph’s programs, like their political advocacy that ensured kosher food for Florida inmates, free books and Jewish learning resources that the local chaplain got from Aleph. But she did not know that Aleph could help her with her children.

Harvey Main, who was introduced to Aleph through his local Chabad rabbi at the very beginning of his incarceration, says it is critical to have an advocate in the prison system. “The system is really not geared to meeting the needs of Jews and it is very important to have someone who knows how it all works to speak up and make sure we get what we need.”

Those needs may be spiritual, like asserting to prison officials that there really are that many Jewish holidays during the High Holiday season. But so many of the needs are simply practical, like helping them navigate the yards of red tape around daily things they used to take for granted.

When Katz learned that Marcia had not seen her children in months, he arranged for a volunteer to visit her ex-husband’s house and get him to sign papers allowing the children to visit. He then arranged for a driver to pick up the kids and drive them to and from the facility on a weekly basis giving Marcia and her children the priceless gift of time together every week.

She recalls that first visit which took place after more than a year. As she waited in the family visitation room for her children to enter, she began shaking. “I was so overwhelmed, I kept touching them and hugging them to make sure they were really there and I wasn’t dreaming.”

Understanding the very basic need for caring human connection, some of Aleph’s programs with the greatest impact are those that offer inmates contact with people, be they rabbis, mentors or other Jewish volunteers. Working in partnership with Chabad’s vast network of emissaries and hundreds of rabbinical students, many of whom are prison chaplains, Aleph runs a mentoring program, pairing individual inmates with professionals and guidance counselors who meet on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. “One way or another,” says Katz, Aleph reaches just about every Jew in prison.

“While we don’t have direct contact with every single one, especially since they come and go so often, we are connected with more than 3,000 inmates on a regular basis,” he asserts. The rest are offered services through their local Jewish or non-Jewish chaplains, all of whom work with Aleph in some capacity. “If there are 600 US prisons with Jewish inmates, we are working with 600 chaplains.”

“You Are Not Alone”

Rabbi Friedman says that he doesn’t think that “the Aleph student rabbis are aware of how much they do for the inmates.” Prisoners are astounded that these young people take time off from their vacation to “drive up and down the coast visiting people they’ve never met, and who they would otherwise probably never meet, just to be good to another human being.”

Main will never forget one rabbi who used to drive 3 ½ hours from New Orleans, every week, to his isolated prison “in the middle of nowhere” to study Torah with them. Or the Chabad students who slept across the street in a camper that Aleph rented in order to be there on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur to lead services.

“Our priority has always been to tell these marginalized Jews, ‘You’re not alone, you’re not forgotten. There’s someone out there who cares about you.’ We’re there to comfort them, to advise them and to show them that the Jewish community cares about them,” Rabbi Katz says.

Friedman met one inmate whose violent gang life landed him in a high security facility. He’d never met a rabbi until a Chabad rabbinical student came to visit him. It proved a breakthrough moment for the inmate who was sure he’d been forgotten.

“He was shocked that someone had come to visit him,” Friedman says. “He told me he did not know who that student rabbi volunteer was, but if he ever met him again he’d want to tell him how that one gesture of kindness helped him change his life in profound ways.”

“,”

Anti-Semitism and Advocacy

One of the unique challenges Jewish prisoners face in prison is anti-Semitism from other prisoners as well as from prison guards. Declaring one’s Judaism by requesting kosher food or attending religious services can leave prisoners open to verbal attacks or worse. Many correctional facilities in the state have white supremacy activity, and Rabbis Lew, Friedman and Katz have all personally interacted with many neo-Nazis. Katz says that verbal harassment can easily lead to physical violence.

“In prison we find anti-Semitism at levels 100% more than what you would find on the street,” says Katz. To combat it, Aleph will “go all the way up to the highest levels to make sure that the perpetrators—be they guards or other inmates, don’t get away with it.”

Working with lawyers and government officials, Chabad activists advocate for prisoners regarding unfair treatment, anti-Semitism, lack of medical care, denial of religious freedoms and other issues. Federal lawsuits have been filed over the unavailability of kosher prison meals in various states, and Aleph has had to fight prison after prison to allow Jewish ritual objects in.

Katz tells of one state that changed its status quo in the early 2000s prohibiting inmates from keeping tefillin as part of their personal property because the tefillin straps could be used as a weapon. The new rule would only permit tefillin in the prison chapel. But with the chapel often closed, many Jews could no longer fulfill their daily obligation.

The situation prompted Katz to draw up a list of all the potential weapons that could be purchased in the prison canteen including lighters, shoelaces, heavy metal locks, soda cans, razor blades and more. He drafted an email to a high-ranking prison director describing the double standard that prohibits tefillin but allows other potential weapons, and demanded that the ban be rescinded. The prison official complied.

Today, when running into similar issues, Katz says they resort to precedent to leverage other prisons to allow for Jewish rituals to be performed in their entirety, but they are not always successful. Many prisons still do not allow Jewish women to kindle Shabbat candles on Friday night and holidays, and traditional menorahs are frequently banned as a fire hazard.

Family Support

Aleph also works with families of Jewish inmates to identify the services they need. Different families require services as diverse as support groups, spiritual counseling and financial assistance. “Some families are left homeless when the breadwinner is incarcerated. Others are just relieved if they can pick up the phone to speak with someone who empathizes,” he says. “There is no blueprint.”

“For every prisoner, there is also possibly a mother, father, spouse, sister, brother or child” suffering from the stigma and devastation of having a family member locked up. “It’s important for families to know they’re part of the Jewish community, that we don’t judge them and that they’re not alone.”

The organization raises funds to assist families with basic needs and provides 100 children of inmates with a Jewish overnight camp experience every summer. Marcia’s children, Abigail and Mike attended Aleph’s summer camp during the summers that their mom was in prison. As well, volunteers would visit their home, stocking the refrigerator with groceries and taking them shopping for school clothes. They were welcomed to community events and received personalized gifts on Chanukah.

Mike connected with his Jewish identity and soon switched to a Jewish day school with full scholarship. When he was 12 years old, he began studying for his bar mitzvah, fascinated, said Marcia, with his newfound knowledge and traditions.

To Marcia, most meaningful of all was the opportunity to bond with her children while in prison, that transformed her life. “Rabbi Katz took care of everything to make sure I had constant contact with my kids. People drove them to see me every week, they gave them cell phones to call me,” she says. “They kept my family together” during the toughest times, preparing the way for the family to become whole again after Marcia got out.

“,”

Tricky Transitions

Aleph’s programs have been designed to meet four goals for the inmates, Katz explains. “We want to help ensure that prisoners are sane on their release. We want them to know that there’s a Jewish community who cares about them. We want them to come out as law abiding members of society, and we want them to be able to live a Jewishly engaged and meaningful life.”

While the horror of incarceration ends with release from prison, freedom can also mark the beginning of a new set of problems. When an inmate returns to civilian life, Aleph connects them with their local Chabad House and does their best to assist them with job applications, medical needs and housing, depending on need. Limited by budget constraints, the organization often relies on Chabad emissaries on the ground to assist with support after the release.

“Unlike other organizations, we aren’t really funded by the people we service,” Katz says, explaining that he wished he had the resources to properly support the reentry process. “While some of our constituents are not financially able to support our work, many who can don’t because they want to put that sad and painful time of their life behind them.” Still, Chabad rabbis do whatever they personally can to help inmates out as they start living their normal lives.

Marcia got out six months early for good behavior. On that first Saturday after her release, she watched as her son was called up to the Torah at a large Chabad synagogue. Standing next to him was another bar mitzvah boy, Rabbi Katz’s son, Levi, also celebrating his milestone transition into adulthood. The two could not look more different: Mike, the biracial son of a 39-year-old single mother on parole, who less than a year earlier had no connection to his Jewish faith, and Levi, a young Chabad boy who grew up in the thick of Southern Florida’s Orthodox Jewish community.

Both were called up to the Torah equally, both were lifted on chairs in the middle of a dancing circle of rabbis, both celebrating the next step in their life journeys. It was the crowning moment for Marcia and Rabbi Katz, who played a major role in seeing Mike and Marcia to this point.

After her release, Rabbi Katz helped Marcia find affordable housing in a decent neighborhood and reached out to her brother, who agreed to help pay for the deposit. “Rabbi Katz helped me through every step. He helped me turn on the electricity, he called me every day, he invited us for Friday nights.”

Today, Mike is in yeshiva and attends Shabbat services every weekend. Marcia attends synagogue when she can, as the busy mother is now working two full time jobs. Abigail maintains a high GPA at her high school where she is in a special pre-medical school track. Fully integrated into a Southern Florida Jewish community that once seemed so foreign, the Singers are looking ahead with hope.

Rabbi Friedman says Marcia’s story is not unique. He recalls a former inmate who contacted him years later to thank the rabbi for helping turn his life around. As the chaplain began to protest his praise, the inmate insisted: “Don’t tell me you were just doing your job. You were doing what the Rebbe taught you to do. And it worked.”

Be the first to write a comment.