Mitzvah Tanks have been a fixture on the streets of New York City for nearly five decades. Today, they can be spotted in many places where Chabad is active. Parked on street corners and near college campuses, these specially decked out RVs carry rabbinical students who invite Jewish pedestrians inside or curbside, with the offer to connect over a mitzvah.

The unconventional approach was a hit in the countercultural heyday of the ‘70s. But in an age of targeted online ads and sophisticated social engagement techniques, why does Chabad continue to canvass for Jews on the street? Does stopping people at random to talk about Judaism even work? And what actually happens inside a Mitzvah Tank?

Ubiquitous, peculiar, and at times, controversial, Mitzvah Tanks elicit mixed reactions wherever they go. Lubavitch International takes a deep dive into the inimitable world of the repurposed RVs that bring old-school Judaism to high-traffic metropolises around the world.

“Excuse me, are you Jewish?”

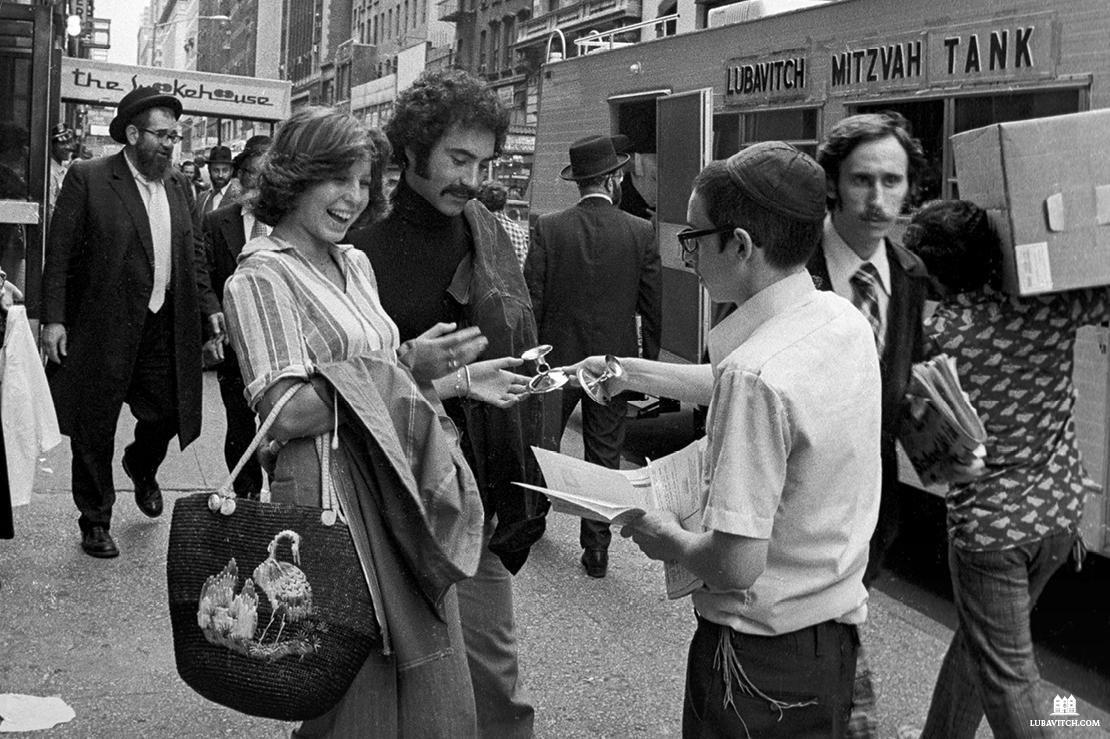

It is a sight familiar to many in New York City: young rabbinical students in black hats and suit jackets standing in front of an RV covered in signs promoting Jewish practice. They approach New Yorkers at random with the startling question.

In an average four-hour shift on “Mitzvah Tank duty,” a rabbi may approach as many as 200 people, hoping to reach a Jew who may benefit from an impromptu spiritual experience.

The question is direct and the responses vary. Many move right along, averting their eyes and quickening their pace. It is New York, after all. Others respond with a “no” expressed in tones ranging from annoyed to apologetic. Still, others reply, “Not today,” “I’m Irish!” or “Not interested,” walking away with a curt nod.

Like clockwork, the undeterred young student wishes each one a practiced and polite, “Have a great day!”

There is rejection after rejection. Then an eager looking older couple approaches the RV. “Are you Jewish?” No. They are tourists from Norway who want to know if they can snap a photo of the boys, who smile obligingly.

But occasionally, there is a yes.

On an early Friday afternoon in the winter, a man quickly approaches the Mitzvah Tank parked at the corner of 51st street, pushing up the sleeve of his coat jacket as he steps onto the vehicle. He’s done this before. “I’m late for a meeting, so let’s make this fast boys.” The yeshiva students do not need to be asked twice and are already wrapping tefillin straps halfway up his arm.

The next person who passes by is a 24-year-old college student from Chicago.

“Excuse me, are you Jewish?”

Taken aback, she replies with a tentative yes.

“Would you like some Shabbat candles to light Friday night? It’s a mitzvah that brings more light into the world.”

“My grandmother used to do that,” she says hesitantly.

“It’s easy, I promise! All the instructions are inside this kit. Just light candles at 5:18 this evening to welcome Shabbat.”

“Ok, I guess. Thanks.” She pockets the candles and hurries around the corner.

Bringing Judaism to the Streets

Since their inception, Mitzvah Tanks have activated the laser-focused mission of Lubavitch: bring Judaism to Jews wherever they are. Enthusiastic Chabad representatives, typically yeshiva students between the ages of 15 and 22, strive to share Judaism in a positive and accessible way, through action-focused Jewish rituals that help Jews of all backgrounds connect with their faith.

In 1988, Rabbi Levi Baumgarten started making rounds on the Mitzvah Tank circuit as a 25-year-old newlywed. He never stopped. His “Chabad House on Wheels” is the longest consistently running Mitzvah Tank in Manhattan, where he has interacted with an estimated 500,000 people over three decades.

“We are there to help facilitate people in doing a mitzvah, whether that is putting on tefillin, lighting Shabbat candles, taking part in a seasonal mitzvah, or just hearing a Torah thought,” the rabbi shares. “Our goal is to give people the opportunity to express their Jewish identity and perhaps inspire deeper spiritual exploration.”

The on-the-street approach is intended to reach people in their daily lives, reminding Jews to pause for a moment of spiritual engagement, not just in a synagogue or on the High Holidays, but in the everyday.

Mark Oppenheimer, a lecturer in English at Yale University, co-host of Tablet Magazine’s podcast Unorthodox, said that, while being called out on the spot and asked, ‘Are you Jewish?’ can be painful for some, “those who are secure in their own Judaism don’t get offended when people challenge them or ask them to identify on the street.

“The people who are most troubled by [these efforts] are themselves uncertain of who they are. People who have clarity where they stand don’t feel judged when they are asked to engage, or when others disagree. Having to answer that question has brought them closer on a journey to their authentic self.”

Countless Jews have experienced a taste of their heritage for the first time through a Mitzvah Tank-enabled interaction, with a spontaneous bar mitzvah or extemporaneous Torah lesson. These moments have a transformative and lasting effect. A 1998 survey, conducted by a major Israeli newspaper, collected information about Israeli Jews and the growth of their personal religious observance. Interestingly, it noted that the first contact for most respondents was neither a seminar nor a Torah class, but rather the observance of a mitzvah, either through an experience at the Kotel or an encounter with a Mitzvah Tank.

“People want to feel that they are part of something bigger than just themselves, and rituals connect,” explains Joseph Telushkin, noted rabbi and author of the acclaimed biography, Rebbe. Chabad’s concrete, “ask” to do a mitzvah, makes the interaction meaningful and tangible.

For all their spectacle, the Tanks are not a sideshow. Rabbi Mordy Hirsch, co-director of the Mitzvah Tank Organization, under the auspices of Lubavitch Youth Organization, explains that the mobile outreach centers are an important complement to Chabad’s various other activities. “Chabad has always met people wherever they are,” said Hirsch. “That’s why we send emissaries to every corner of the globe. When people moved online, Chabad emissaries met them there. In our multi-pronged approach to connect with Jews everywhere, of course, we are going to be going out in the street! That’s where people are.”

Yeshiva students regularly connect Jews with their local Chabad so that Jews who are inspired by the Mitzvah Tank encounter can deepen their experience of Judaism back at home. With Chabad programming growing ever more sophisticated, the Mitzvah Tanks present a throwback engagement technique that cuts to the essence of the Rebbe’s mission.

“We aren’t trying to impose religion on other people,” said Hirsch. “If they say no, we try the next person. But, so many people are looking for connection and it is a gift to be there for them. Just the simple act of telling people that they are valued and that their Judaism has meaning, is incredibly powerful.” Thousands of non-Jews stop by Mitzvah Tanks as well, sometimes out of curiosity, other times simply seeking a good word or spiritual guidance. It is this hope–to be of spiritual service—that keeps the students on the street, in rain or shine.

“Every guy who has done this has their own story that lives with them,” said Hirsch. “For me, it is a man who we later learned had come to Manhattan looking for a building to jump off of. He was struggling and wanted to end his life. He was stopped by a student near the Mitzvah Tank and was asked to do a mitzvah. The man was so startled by the boy’s willingness to share with a total stranger that he stepped inside the Mitzvah Tank just to listen. He decided to return home that day, googled his local Chabad, where he found support and has since found a life of purpose.”

Not every story is as dramatic, but every Mitzvah Tank regular has at least one powerful personal exchange they can share. Those that have been in the trenches for a while can rattle off tale after tale of encounters that have been transformative–to both parties.

Michael Sherek, a 54-year-old businessman in the garment district, had his first Mitzvah Tank encounter with Rabbi Baumgarten in 1988. Sherek was a year out of college and was walking through the streets of Manhattan with a friend when they noticed a Mitzvah Tank. Sherek was too shy to approach the Tank as he had never had a bar mitzvah, but his friend insisted.

Sherek put on tefillin. Something clicked. The next week he found himself seeking out the Mitzvah Tank again with questions about his Jewish roots. Week after week he returned, with new questions each time. Eventually, Sherek set up a regular study schedule with Baumgarten to slowly explore and reclaim his Jewish identity.

“It wasn’t easy,” said Sherek, who had grown up without a basic understanding of Jewish life and spiritual practice. “I felt less of a Jew than [Baumgarten]. When I shared my feelings with him he told me ‘When I have a minyan and you are the 10th man, you are as equal a Jew as anyone else.’ I started to feel better because the focus was always positive. The more you do, the more connected you are to G-d.”

Sherek is now fully engaged in his Judaism and his daughter attends the Hebrew School at Chabad of the West 60s.

Tanks Against Assimilation

The very first Mitzvah Tanks date back to the spring of 1974. The idea came on the heels of a traumatizing slew of events. Months after the Yom Kippur War in Israel, and days after a gruesome terror attack during a high school field trip in Ma’alot killed 22 teenagers, the Lubavitcher Rebbe reached out to his Chasidim and encouraged them to redouble their efforts in mitzvah outreach. The Rebbe had already been launching mitzvah campaigns to engage Jews in traditional rituals like tefillin. Now his dedication to these efforts found new urgency.

Rabbi Sholom Duchman, a young yeshiva student at the time, recalled that he and his friends were galvanized by their teachers to reach out to unaffiliated Jews and that enthusiasm for the mitzvah campaigns reached a fever pitch in Chabad circles.

“If we were already going out to the streets to engage with Jews,” said Duchman, “we wanted to make the biggest possible impact.”

Then, one day shortly after taking to the streets with their ever-present tefillin, the group’s activities came to an abrupt halt with a downpour of heavy rain. Together, the students concocted the idea to rent step vans where people could hop inside for a “Jewish rest break” and do a mitzvah. One technically-proficient student rigged a speaker system to blast lively Jewish music. The mitzvah mobiles drew in more Jews than ever before.

The grassroots initiative was welcomed with approval by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, who further suggested they replicate—a painting that was gifted to the central Chabad library—of a pair of tefillin with its straps wrapped like the treads of a tank—and hang it on the vans.

A few days later, New York Times reporter Irving Spiegel visited 770 accompanied by the Rebbe’s secretary and Chabad-Lubavitch spokesperson, Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, and asked about the colorful trucks parked outside. Referencing the painting on the trucks, the Rebbe later told Rabbi Krinsky, “Tell him these are our tanks against assimilation.”

With a title handpicked by the Rebbe, the outreach vans became officially known as “Mitzvah Tanks.”

As the Mitzvah Tank initiative moved into its first winter, it became apparent that people were not willing to step into a freezing truck to do a mitzvah. Problem-solving once again, the enterprising young students rented mobile homes with proper heating. From that day forward, the mobile home became the Mitzvah Tank of choice.

Mitzvah Tanks bearing the banner, “Mitzvahs on the spot for people on the go,” were soon spotted in metropolitan cities from London to Tel Aviv, regions from South Florida to Brazil, and eventually, to the outbacks of Siberian Russia and rural Australia.

“The Five Stages of Being Asked If I’m Jewish by Chabad”

The Rebbe’s prediction that the vehicles would be “tanks against assimilation” proved proficient. After all, it is impossible to blend in and hide your Jewishness when your identity is being called out on the street. For better or worse, the public display of Jewishness and the straightforward question, asking people on the street, “Are you Jewish?” always gets a reaction. One Jewish writer for The Gothamist referred to Mitzvah Tanks as a “mobile guilt trip” that always comes around the Jewish holidays. Many others are annoyed or even personally offended by the question.

Stephanie Butnick, a cohost of the podcast Unorthodox, said that she’s experienced what she calls “the five stages of being asked if I’m Jewish by Chabad—annoyance, anger, guilt, shame, and acceptance.”

Some are offended at public inquiries about their personal faith or consider the question “religious profiling.” Still, others are offended not to be asked. “What? Don’t I look Jewish enough?” Some are inspired and delighted, some run in the other direction. Some lash out, even going so far as to accuse Chabad of inciting anti-Semitism by “harassing people on the street.” But no study has ever proven that anti-Semites lower their bigotry when Jews hide their Jewishness.

In 2017, the hosts of Unorthodox spent the day with Chabad’s Mitzvah Tank and tried their hand at asking people on the streets of New York if they are Jewish. Mustering up the courage only to get waved off, Butnick gained a “new appreciation for our Lubavitch friends. This is not easy work.”

At times, people can react with exceptionally crass or hurtful responses, perhaps forgetting that the 16-year-old boy on the receiving end of their rude comment was just there trying to do some good.

The time-wisened Baumgarten said that, over the years, he has heard it all. “I took upon myself that even if someone swears at me, I respond with a pleasant ‘Have a great day, I hope you feel better, I’m sorry if I offended you.’”

Often, the positivity will inspire a retraction as people question why they were so rude. Baumgarten has met many who told him that after they denied being Jewish to him or another Mitzvah Tank emissary and refused tefillin, they then went home and dug out their pair from the attic and put them on.

Rob Cohen from Washington, D.C., is more emphatic. “If [people] are offended, they should work to ameliorate their own insecurities that keep them from merely politely declining or ignoring innocent inquiries by people with different culture, value, and priorities.”

In an op-ed for the Forward, Rabbi Joshua Krisch, a Chabad emissary at Ithaca College, wrote that affiliated Jews who were offended by the question should “check their privilege.”

“For every ‘no’ or angry, privileged Jew who stomps off (indignant, outraged that someone who doesn’t look like him or her dared to speak out of turn) there’s another Jew who has never had access to a set of tefillin, doesn’t know how to ask to try it, and may not have another opportunity to do so.

“Many Jews did not have that luxury and will never have the option to put on tefillin unless a [Chabad representative] stands on a street corner bellowing, ‘Excuse me, sir. Are you Jewish?’ We’re making mitzvot accessible to a Jewish population that won’t come to your progressive synagogue services or seminars, or who wouldn’t set foot in one of your community outreach events,” he continued.

This proved true in the case of Aviva Miriam Patt who shared that she used to find the Mitzvah Tank approach obnoxious. As an observant Jew, she felt condescended by the notion that she needed guidance and reminders about doing mitzvahs.

“Later, I met a Lubavitcher rabbi at a Chanukah party and was surprised and a little offended when he asked—everyone, not just me—if we wanted Chanukah candles,” she said. “How ridiculous, I thought, anyone who wants to light candles knows where to find them and can get them for themselves. But,” she continued, “then I saw people take him up on his offer, some saying that they hadn’t lit candles since they were children or since their parents died. I realized then what a genuine kindness it was for him to offer.”

“In the years since then, this same rabbi has provided me with shmurah matzah for the Seder, something I used to do myself and can no longer afford.”

Daniel P., a middle-aged Manhattan businessman, often passed by Mitzvah Tanks on his way to work and never responded. One day, when approached by a yeshiva student he instinctively said, “I’m not Jewish.” The denial weighed on him and continued to tug at him whenever he saw the boys. A few months later, Daniel’s father passed away. Remembering the guys from the Mitzvah Tanks, he finally sought them out looking for a way to say Kaddish. He was welcomed onto the Mitzvah Tank with open arms.

Interactions are not one-time occurrences, as the Chabad representatives build relationships with returning visitors. Baumgarten has gained a reputation and can usually count on engaging with up to 400 people who come by each week. A full-fledged community has blossomed around his “Chabad House on Wheels.” When he throws a Chanukah or Purim party, almost 500 people show up.

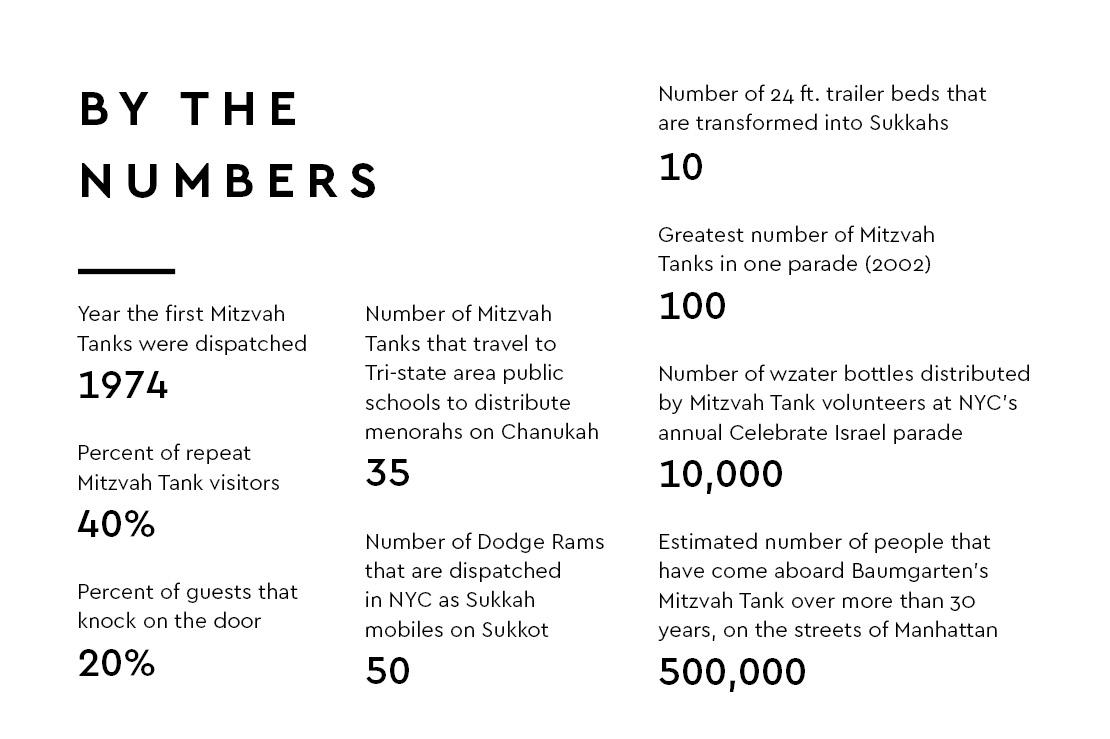

At least 40% of weekly visitors are returning guests. Another 20% reach out of their own accord, either knocking on the door with a question or coming because they were referred by a friend.

“There are people from all walks of life. Some are very religious and stop by looking for a minyan or asking about the closest kosher restaurant. Others come in just to get their spiritual recharge—it is an oasis right in the middle of their busy workday.”

Adapting to Coronavirus Times

On April 5, 2020, three days before Jews around the world would sit down to quarantined Passover Seders in their own homes, a fleet of 10 LED-screen trucks from Crown Heights, Brooklyn, embarked on a mission. It was the height of the pandemic crisis in NYC, with strict stay-at-home orders, hospitals and communities in crisis, and Jewish communities grappling with the challenge of celebrating the holiday of freedom under lockdown. With Judaica stores closed and grocery store stock unpredictable, many Jews worried about securing their Passover staples.

“Every year, days before Passover, we distribute thousands of pounds of shmurah matzah at our annual Mitzvah Tank parade,” said Hirsch. The parade is held every year to honor the anniversary of the birth of the Rebbe on the 11th day of Nissan. “This year, as we saw that things had to be different, we decided that we were not going to downgrade our goal because of the pandemic.”

The parade was quickly adapted to comply with social-distancing regulations. Instead of in-person RVs, the office rented a slew of LED trucks, with a flashing message to remind the 1.5 million Jews living in New York City that Passover was coming. Loudspeakers and signs advertised a website and hotline where people could order a free box of shmurah matzah delivered to their door.

“We mapped out the five boroughs and arranged a route that drove through every single street in New York City. We recorded a professional voiceover to wish everyone a Happy Passover and shared a message of strength in the face of the challenge,” Hirsch explained. The roving billboard PR campaign worked. A special phone hotline set up for orders and www.Matzah.nyc were flooded with requests for Passover assistance. On Twitter, requests for matzah and messages of thanks poured in from every corner of the city. One grateful father shared that his daughter, who was working twelve-hour shifts as a nurse in a Manhattan hospital, “now had matzah thanks to Chabad.”

“We had to extend the deadline for matzah orders three times, up until Passover eve,” said Hirsch. “We hit our goal numbers of matzah distributions—without ever having to stop someone in the street!”

Hours before sitting down to his own home Seder, Hirsch returned the last of the trucks’ keys to the rental service. As he was about to walk away, he turned to the agent, with Chabad’s iconic open-ended question of possibility, and called from six feet away,

“Excuse me. Are you Jewish?”

Rigka

Fabulous articles. Try enlightening

Yarden

What an amazing group of people bringing mitzahs to everyone!!!!! Jews need to come together in these times of uncertainty!!!!! Even the tiniest mitzvah can make all the difference <3 Something as simple as lighting the Shabbat candles can go a long way. Thank you to the mitzvah tankers for bringing good to the world!!!! It is truly sad how being religious is frowned upon by many people who are Jews. It comes from a place of simply not knowing what Judaism is all about, wanting to be politically correct/accepted in modern society, and fear of antisemitism. It's truly sad because we have such a beautiful religion. Thank you to those who pray on a daily basis for the Jewish people and for everyone in the world.

none of your business

I was asked this in Paris . . . three times in as many days. I cannot believe that people would so forthrightly and rudely violate my privacy by asking such a question. The question is in violate French law and being asked for any personal information by a stranger is so absolutely offensive that I can’t believe it happened.