In the winter of 1985, Michael Gleizer was working as a librarian. At nights and in spare moments stolen from his young family, he painted the images that had made him a pariah in the Soviet art world—a bride and groom standing beneath a wedding canopy, a woman circling the flames of the Shabbat candles with her hands. They were never exhibited.

A painter and illustrator whose work the art historian Mikhail German once compared “emotionally and plastically to the bitter poetry of Marc Chagall, Sholem Aleichem, and Anatoly Kaplan,” Gleizer’s art is inextricably bound up with his strong Jewish identity—a bond would lead him on an unusual artistic journey.

In 1993, at the age of forty-seven, Gleizer immigrated to America with his family. Having lived the first half of his life without the freedom to practice his faith, “America gave me an opportunity to freely plunge into religious life,” he says. “I felt how Jewish spirituality is close to me, to my soul.” The artist settled in Mill Basin, Brooklyn, and began attending synagogue regularly.

In the decades that followed, he produced a large and diverse oeuvre that spanned graphic arts, costume design, and an endless array of neo-impressionistic oil paintings. He painted interior studies of family life, romantic depictions of figures immersed in nature, and surreal images of regular people flying through the air.

Finally free to practice his faith, Gleizer experienced a simultaneous flowering of creative energy. He also returned to a familiar theme, this time with a new perspective.

Menachem Mendel in the Shtetl

Gleizer’s Jewish art began, like so many Jewish stories, with a ne’er-do-well, a shlemiel drunk on illusory dreams of wealth and grandeur.

Born into an observant Jewish family in Kyiv in 1946, Gleizer grew up without synagogues, Jewish schools, or kosher food. Nevertheless he maintained a strong Jewish identity, speaking—and reading—Yiddish at home.

Stories of Tevye, a traditional dairy farmer burdened by poverty and a bevy of independent-minded daughters (later adapted in America by Joseph Stein as Fiddler on the Roof), were among the few sanctioned expressions of Judaism in the Soviet Union. For Gleizer, Sholem Aleichem’s wry, humorous stories bore the full weight of his Jewish identity, an identity bound up with a sense of loss. As a young artist he returned frequently to Sholem Aleichem’s characters as a theme, because, he says, “I wanted to preserve this disappearing life that impressed me . . . and was living in my memory.”

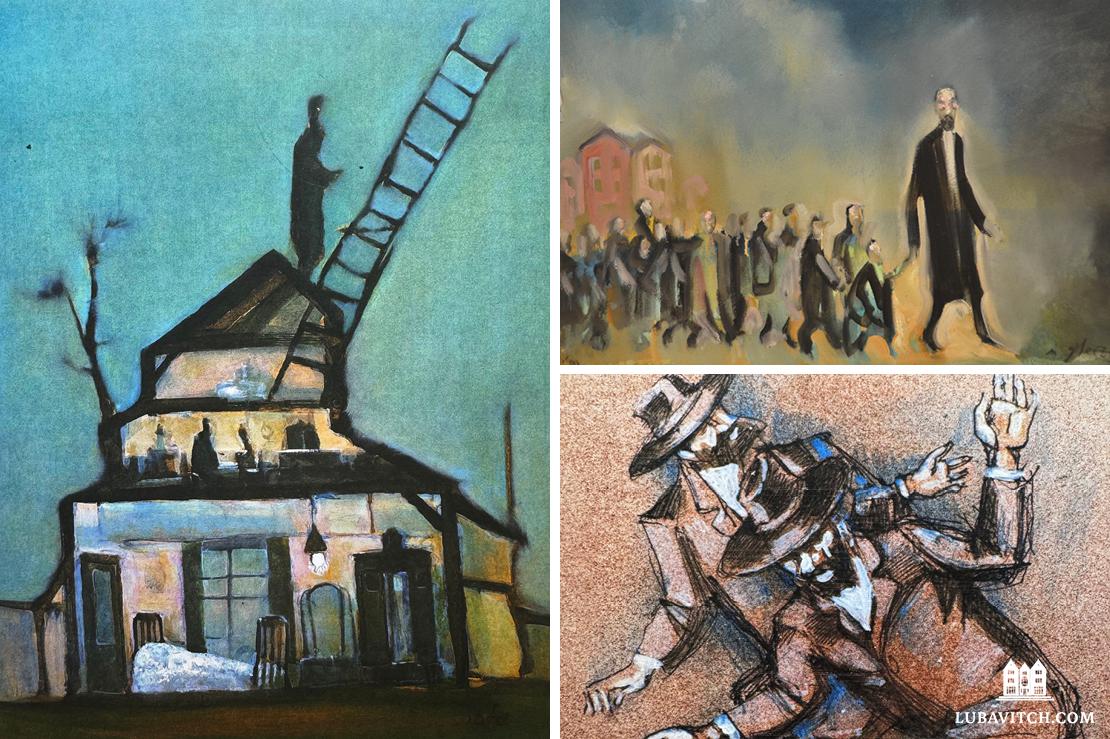

Still, Gleizer managed to convey some of the humor, and the subversive undertones in these stories, which invariably pit Jewish characters against a society undergoing political and economic change. His painting “Menachem-Mendel in Shtetl” depicts the classic archetype of the unlucky shlemiel, the schemer found in both Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye stories and his eponymous 1913 collection. Here he is seen teetering on a diagonal dressed in a fancy cream-colored overcoat and shoes adorned with spats. He carries a little satchel, no doubt filled with false promises that will fuel the misadventures of the naive Tevye.

Gleizer’s budding career was quickly cut short when, after Israel’s Six-Day War in 1967, the Soviet government launched an anti-Israel media campaign in which, among other accusations, Jews and Israelis were compared to Nazis. In 1973 all Jewish art was banned.

Reflecting on that time and the precarious existence he shared with the reeling Menachem-Mendel, the artist recollected: “All hopes and dreams are in vain. The gates will always remain shut for you if you are a Jew.”

New Space for Grief

Beneath Tevye’s dry humor, of course, is a current of anguish, and as the Soviet Union tumbled toward dissolution in 1991, Gleizer was finally able to reckon with the darker realities of Jewish life in Ukraine and Europe.

His nine-panel “Babi Yar” commemorates the largest mass murder of Jews by the Nazis during the war against the Soviet Union. Among the 33,771 Jews murdered in this ravine near Kyiv on September 29–30, 1941, were some of Gleizer’s relatives. Yet memorials erected on the site by the Soviets commemorated only “peaceful victims of fascism,” without mentioning Jews. Gleizer’s massive painting breaks new artistic ground, presenting hundreds of indistinct figures struggling to free themselves in the mire of a fog-filled landscape under three horizontal registers of cold, relentless sky.

Gleizer’s early experience with Soviet religious and artistic oppression—and subsequent liberation—presents an alternative to widely held beliefs about the incompatibility of faith and art.

Another painting of that year, “Doctor Korczak with Children,” is one of the rare depictions in art of the famous pediatrician and director of a Warsaw orphanage Janusz Korczak, who refused to abandon his charges as they were marched to Treblinka in August 1942.

But even as he grieved the past, Gleizer was confronting the future. Perhaps unwilling to uproot his family, he had remained in Russia as many of his fellow Jewish artists fled. His painting “Meditation” establishes a frequent Gleizer motif, showing a cutaway view of a multi-story house representing the complex intimacy of family life. In contrast, a lone silhouetted figure on the roof stands next to a ladder stretching up to the sky. The growing need to leave the warm lights and comforts of home to somewhere better and freer presents an existential dilemma that only a radical change can begin to answer.

Breakdancing Rebbes

That change came in the extended hand of Zev Markowitz, director of the Chassidic Art Institute. Familiar with Gleizer’s work from his Soviet years, Markowitz formally invited Gleizer to exhibit in his Crown Heights, Brooklyn, gallery in 1991. This was followed by the publication of Markowitz’s first monograph on Gleizer in 1993. Gleizer moved to New York that year. His work has been exhibited multiple times at the gallery since, and Markowitz is currently preparing a second book focusing exclusively on Gleizer’s Jewish art.

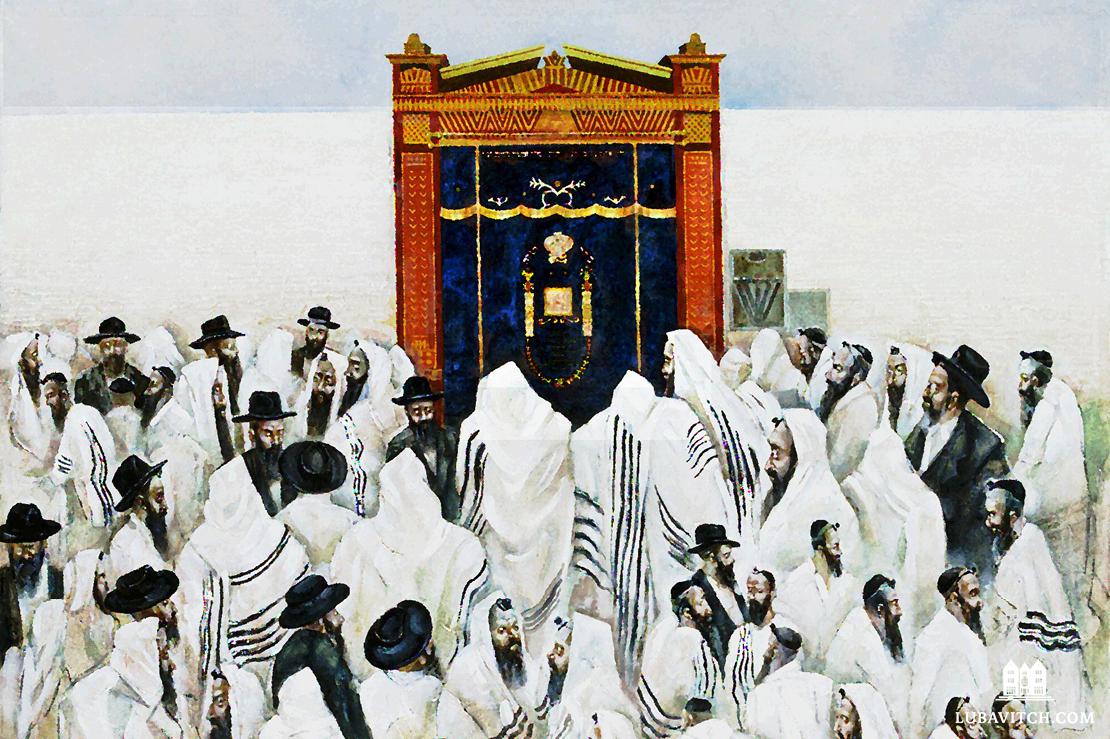

In an absolute expression of joy and freedom, Gleizer’s images in New York blossom with men in prayer shawls. A series of four paintings, “Synagogue” (1993), finds eighteen Jews adorned in tallit and tefillin, milling around a shul, a scene unheard of in Gleizer’s former life. “In the Soviet Union my Jewish themes centered on the everyday life of Jews: dinners, conversations, holidays, and so on,” he said. “In America I was able to, and did, paint more overt aspects of religious life.”

In an absolute expression of joy and freedom, Gleizer’s images in New York blossom with men in prayer shawls.

Perhaps the most notable assertion of Jewish practice is “770” (1994), depicting over sixty men in an odd moment after the morning services at the Chabad-Lubavitch headquarters. They are pointedly not lined up praying toward the ark; rather, they are facing every which way, caught in a moment of random community that expresses a deeply felt freedom to be individuals, unified by Jewish faith and practice. The choice of subject was not accidental. Gleizer had rented a studio in Crown Heights, opposite the Chai Gallery, where he worked every day for twenty-five years.

Gleizer’s memories inform more complex works that contrast conformity and youthful independence. The 1998 image “In Museum” depicts a young boy with his back to us, staring at an enormous painting of an entire congregation of tallit-clad men (the original painting, which Gleizer recreates here, is by the Chasidic artist Zalman Kleinman). The confrontation between Gleizer’s Russian past and his American religious freedom is made even more complex by the shadowy figure beyond the door on the right edge of the image.

But what is truly unique in Gleizer’s later works is a delicacy of touch and sense of humor rare in Jewish art. His ability to see beyond clichés and find the vibrant soul of Jewish practice informs a pair of Chasidim in “Dancing” (2003). While their oversize black hats and suits are straight out of central casting, it is the totally unique crouching steps and twisting gait that transform them into breakdancing rebbes. Likewise, in “Before Sabbath,” Gleizer imagines a pair of adult Chasidim traversing the streets on scooters. One carries a tallit bag tucked under his arm, while his friend is bearing a bouquet of flowers, surely a present for his wife. In this series of watercolors we see the magic energy of a Jewish life fully lived in the freedom of Brooklyn.

Gleizer’s Jewish art is one strand of many in a lifetime of artistic output. Yet his Jewish sensibility can be seen in almost everything he produced, he says: “I always present in [my paintings] Jewish elements, whether in the Soviet Union or the USA.” Gleizer’s early experience with Soviet religious and artistic oppression—and subsequent liberation—presents an alternative to widely held beliefs about the incompatibility of faith and art. At the same time the struggle to develop and preserve his Jewish identity under duress has led to a deeper awareness of what he shares with all people.

“Even when painting Jews, I strive to express qualities and problems common to all human beings,” he says. “The deeply national develops into something universal.”

This article appears in the Fall/Winter 2024 issue of Lubavitch International, to subscribe to the magazine, click here.

Be the first to write a comment.