Anatoly Kaplan: The Enchanted Artist

Beit Avi Chai Gallery, Jerusalem

In a gray, dimly lit room, a mother ties a red kerchief atop her daughter’s school dress. Behind them, even more deeply in shadow, sits a bearded man wrapped in a traditional black and white tallit, bent over a prayerbook.

The scene seems innocent enough, and yet, small details hint to the influence of powerful forces beyond the domestic sphere: The red kerchief was an obligatory symbol of membership in the Communist youth movement. The religious man is surrounded by two red curtains, which both serve to frame his figure and also suggest that he may need to hide at a moment’s notice. Even in 1976, when this painting was created by Russian-Jewish artist Anatoly Kaplan, it was nearly impossible to be an observant Jew in the Soviet Union. Like much of Kaplan’s work, Interior draws us into a world of tensions, memories, and contradictions inherent in the experience of Jews in Communist Russia.

The persistence of sparks of Judaism under communism is a topic of great interest to me. Though the Chabad movement has long been associated with America, the spirit of Lubavitch was first nurtured in Russia, both under czarist rule and after the Russian Revolution, when religious practice was suppressed and ultimately outlawed. Under constant surveillance by Soviet authorities, Chabad Chasidim took great risks to ensure that children were taught Torah. In a sense, Chabad’s collective memory and ethos were forged in the crucible of communism, in the midst of immense hardship that led to heroism—the sheer difficulty of Jewish observance driving home its precious necessity.

Even as a Communist-sanctioned illustrator, Kaplan was trying to articulate something that was being actively suppressed in the culture around him.

With all this in mind, last spring, I visited “The Enchanted Artist” at Beit Avi Chai in Jerusalem, the first exhibit in Israel to showcase the work of Kaplan (pronounced with the emphasis on the second syllable). Kaplan was no Chabad rabbi, though he was born to Chasidic parents in the predominantly Lubavitch town of Rogachev, in what is now Belarus. Like many Jews of his generation, his journey out of the shtetl toward university art study in Leningrad, coupled with communist pressure, led him to abandon Jewish faith and practice. Yet Kaplan was well aware that communism was no paradise. Though he became an acclaimed artist, he lived much of his life in a communal apartment in Leningrad, earning only 2 percent commission on works sold, with the rest taxed by the Soviet government. The exhibit relays how he painted his Jewish works on the back of his door to keep them away from neighbors’ prying eyes. Even when his artwork began to be exhibited in Europe and the United States, Kaplan was not permitted to leave the Soviet Union.

There were times under Soviet rule when it seemed like Jewish art was encouraged. In 1920, Soviet authorities allowed the Jewish actor and director Solomon Mikhoels to develop the Moscow State Jewish Theater, a project that attracted a great many of Yiddish-speaking participants. In the book Samarkand, which depicts Jewish life in the USSR during this period, Hillel Zaltzman recounts how even Chasidim like his own aunt and uncle were drawn to participate in the theater. The legendary Jewish artist Marc Chagall made the magnificent scenery in an atmosphere that was full of hope for the possible flourishing of Jewish cultural, if not religious, life. Yet, despite his own promotion of the theater, Stalin ultimately had Mikhoels murdered in a back alley in Minsk, and killed the other participants in one of the infamous purges of writers and intellectuals after World War II. Throughout this terrifying period, Kaplan worked quietly, finding a measure of sanctuary running a decorative arts factory that produced ceramics and glass.

The place where Kaplan could explore Jewish themes with the greatest freedom was as an illustrator, perhaps most famously of the work of Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem. Sholem Aleichem was the rare Jewish writer who was not suppressed by Communist censors—he was even translated and published in Russian, perhaps because they saw in his humorous depictions of shtetl life an opportunity to mock traditionalist Jewish sensibilities. Of course, a deeper look at classic stories like “Tevya the Dairyman” and “The Enchanted Tailor” reveals that they are anything but glib. In truth, Sholem Aleichem’s work explores the tragic difficulty of Jewish life under antisemitic persecution. Kaplan was the perfect artist to illuminate these complexities, and also to add some of his own.

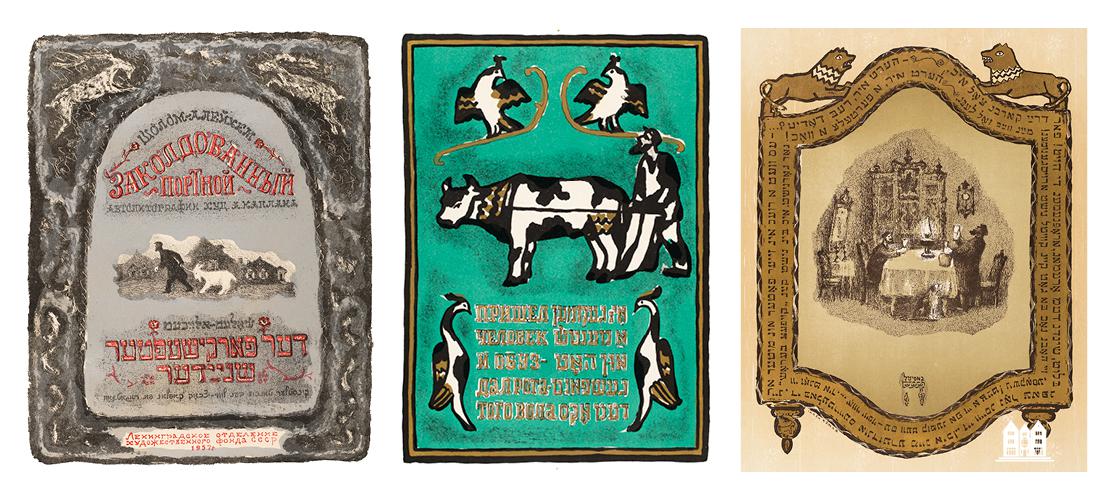

The Beit Avi Chai exhibit gave a place of honor to Kaplan’s Enchanted Tailor series, color lithographs that accompany Sholem Aleichem’s reworking of a classic Chelm tale. In the original story, two residents of Chelm purchase a she-goat to provide milk for their ailing rabbi, but on their return trip, the goat is exchanged for a male billy goat by a cruel tavern keeper, leading them to try to return the goat to the original seller, only for the tavern keeper to do the same trick again, but in reverse. Sholem Aleichem’s version places a poor, pious tailor at the center of the tale, and introduces elements of tragedy and madness. In Kaplan’s rendering, this “enchanted” goat takes on iconic proportions, as his work incorporates goat-shaped illustrations amid other images familiar from Jewish illuminated manuscripts. To an attentive viewer, the goat stands in for something larger, perhaps the ways in which Jews have been scapegoated throughout history.

Kaplan returns to goat symbolism in his Chad Gadya sequence, a bold, graphic set of color lithographs wherein he depicts each verse of the famous Passover Haggadah song. Here, however, the influence of Soviet censors is more pronounced. Created between 1957 and 1961 under the eyes of Soviet authorities, Kaplan’s version of the song replaces the butcher who slaughters the bull with a farmer, who yokes it instead, perhaps a nod to the important nature of agricultural work in the Soviet imagination. Most tellingly, G-d is nowhere to be found in Kaplan’s “Chad Gadya.” Indeed, the Beit Avi Chai exhibit titled this sequence “Chad Gadya Without G-d.” Yet, curator David Rozenson also notes how Kaplan’s choice of traditional religious iconography means that the song maintains its spiritual tone. Even as an illustrator, Kaplan was trying to articulate something that was being actively suppressed in the culture around him.

That tension is nowhere more evident than in Kaplan’s tempera paintings—perhaps the most powerful pieces in the exhibition. In Betrothal, painted in 1976, a Jewish bride and groom, painted in purple, gaze at one another lovingly, imaginatively perched on top of a house—perhaps the one they might build together, or a symbol of their roots in such a home, or even perhaps their rejection of it. Also in purple are two bearded Klezmer musicians (music plays an important role in Kaplan’s compositions). As in Interior, however, the foreground and the background pull in opposite directions: this traditional Jewish couple is set against a bright red background with mixed-gender couples dancing, it seems, to a different kind of song. The question of which world this young engaged couple will join remains open, yet Kaplan reminds us what is at stake in the decision.

Like much of Kaplan’s work, Interior draws us into a world of tensions, memories, and contradictions inherent in the experience of Jews in Communist Russia.

Not everyone agrees with this interpretation, however. Zhenia Fleisher, a Russian-Israeli chemist whose father was a friend of the artist, told me that Kaplan was not an “anti-Soviet” artist. Kaplan loved Leningrad with the same passion that he loved Rogachev, Fleisher says, perhaps even more so; but “his lifelong work was an attempt (he thought it was futile) to keep the Jewish world of his childhood from disappearing from people’s memory. It was actually a desperate fight against death.” Fleisher describes Kaplan, whom she knew personally, as an “old, sad… Jew in a Leningrad communal apartment who found in his heart the strength and talent and drive to recreate [a] perished world in this art. All the colors, the mannerisms, the stories, the songs, the houses, the synagogues, goats, horses, birds . . . everything his memory held and cherished he put in it.” In truth though, as the exhibit in Jerusalem poignantly expresses, it was impossible for Kaplan to know which elements of his surrounding environment were on their deathbed and which would ultimately endure.

The death of Stalin in 1953 gave a little breathing room to Jewish artists and allowed Kaplan to grapple with his pain over the loss of his parents and childhood home: The Jewish community of Rogachev was first persecuted by the Soviets and then ultimately destroyed, its residents murdered by the Nazis in 1941.

The Beit Avi Chai exhibit began with several of Kaplan’s poignant, drypoint depictions of Rogachev, which were produced during this period. The minimalist engravings, resembling pencil sketches, show everyday scenes from the life of a Jewish town—a wedding, a miller carrying a sack of flour, a young student studying Torah with his teacher. Kaplan seems particularly interested in intergenerational harmony: a grandfather walks tenderly with a grandchild, a bearded older man raises a chicken for the kaparot ritual, with young children looking up to him and following his lead. Later on in the exhibit, the commentary notes that Kaplan’s frequent depictions of grandchildren may evoke his own pain at not being able to have one of his own (his sole child, a daughter, was born mentally and physically handicapped).

The wonderful introductory essay by Rozenson in the museum catalog quotes a letter from the famous Russian writer Leo Tolstoy to the Jewish Russian artist Leonid Osipovich Pasternak: “Remember, Leonid” it reads, “everything will pass away—everything. Kingdoms and thrones, wealth and millions of people—everything will perish. Everything will change. Neither we, nor our grandsons will remain and there will be nothing left of our bones. But if our works contain even a grain of real art, they will live forever.”

For me, it recalled a passage in Samarkand, where Zaltzman describes a farbrengen delivered by a Chasid named Reb Bentcha Maroz, who operated a clandestine religious school during the Soviet period. Zaltzman quotes Reb Bentcha as having shared the following insight: “I was once in Moscow, in the Red Square, and saw thousands of people rushing here and there. In my mind, I asked them: ‘What are you so enthusiastic about? One hundred years ago none of you were here, and in another hundred years none of you will be here, so why the emphasis, and the excitement about matters of this world?’”

There is a connection between these two quotes and Kaplan’s life and work. The composition of Interior suggests that the young girl with her red kerchief represents the wave of the future, whereas the Jewish man praying in a tallit represents the past. Yet the truth would ultimately prove to be the opposite. Whereas the Soviet themes that Kaplan represents in his work now require research and historical data to parse, his Jewish symbols are just as accessible today as they were then. One could even say that Kaplan’s Jewish material is precisely what elevates his artworks from Soviet period pieces—which would make them now mere historical curiosities—into masterpieces with enduring spiritual appeal.

This article appears in the Fall/Winter 2023 issue of Lubavitch International, to subscribe to the magazine, click here.

Be the first to write a comment.