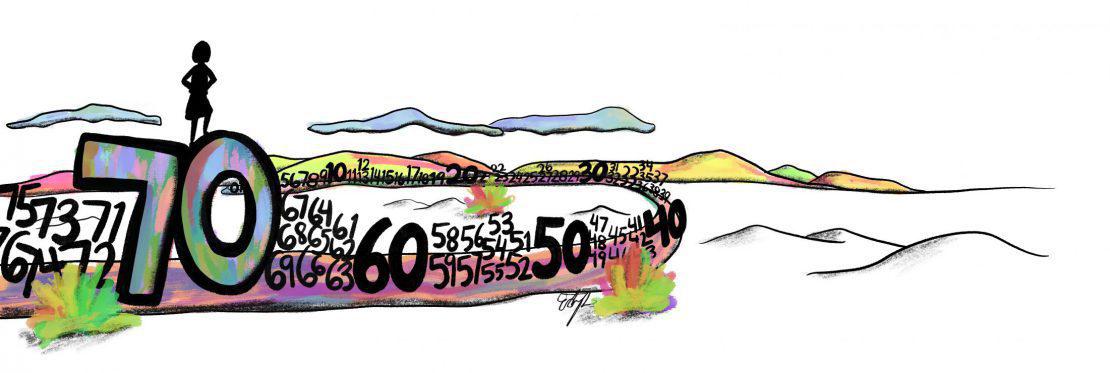

“Five years is the age for the study of Scripture. Ten, for the study of Mishnah. Thirteen, for the obligation to observe the mitzvot. Fifteen, for the study of Talmud. Eighteen, for marriage. Twenty, to pursue [a livelihood]. Thirty, for strength. Forty, for understanding. Fifty, for counsel. Sixty, for sagacity. Seventy, for elderliness. Eighty, for power….” —Ethics Of Our Fathers, 5:22

Yes, it’s happened to me. Like so many other baby boomers, I have turned seventy. Born after World War II, we came of age in the turbulent 1960s. We rebelled socially, politically, and religiously. “Don’t trust anyone over thirty,” was one of our famous mantras. Bob Dylan—one of us—expressed it well in his 70’s song, “Forever Young.” But we didn’t stay forever young. We reached thirty, then forty, fifty, sixty, and now we are in our seventies. Over the last few years, I have found myself looking around at my peers and wondering: who are all these gray-haired people, with their wrinkled necks? How can these be my contemporaries?

As my seventieth birthday approached last October, I was anxious. “It’s just a number,” friends said. But I knew deep down that it was far more. To attain that age in good health would be a blessing from G-d, but where I was heading? Was I really becoming “elderly”? Was I at the threshold of “old age”? The famous line in the book of Psalms (90:10) decrees, “Seventy years is the span of our life, and, given the strength, eighty years.” Not comforting.

I had faced another milestone the previous year: retirement. Israel requires that university professors retire at age sixty-nine. But I still had so much to give. I felt frustrated and even a bit insulted. “We are going to miss you so much, and don’t know what we’ll do without you,” my colleagues and students said emotionally at farewell ceremonies. I knew they meant it, but I also knew that everybody adjusts quickly. After a year or so, they’re not really missing you so much, and in fact, they are getting along quite well without you.

With my formal academic career concluding, who would I now become? What would I do? As a follower of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, I had received many blessings from him during my career. He strongly encouraged me to use my G-d-given abilities and academic position for—as he put it—“special success in spreading Yiddishkeit.” Of course, the Rebbe continually impressed upon every Jew—whether child, businessman, artist, taxi driver or advanced Torah scholar—that she or he was a messenger and emissary of G-d, at every moment, in every situation, and every stage of life. How could I explain that to all of these well-meaning people who told me, “Now you’re retiring; this is your time to have fun, enjoy yourself, and do whatever you want!” They gave me blank looks when I tried.

I felt the need to expand, breathe, fly in new ways. So I interviewed retired friends, asking: How did you do it? How does it feel? What advice can you give me? “Well,” most of them responded, “you just have to try different things and see.” I was still in the dark.

Lurking behind my search, I confess, was also the deep fear that all of us who retire and move into our seventies, eighties, and nineties face: irrelevance as well as gradual physical and mental decline. In the last few decades, thankfully, there’s been an explosion of scientific research on aging, which has revealed the creativity, richness, and neuroplasticity of the older brain—just in time for us baby boomers, the first generation in history to have a good chance at living well for another thirty years.

So what’s everybody doing with all that new time? Retired friends pursue options like traveling to exotic places, volunteering, joining a choir, a book club, a health club, spending time with grandchildren, taking a class at a local community center. All of those are worthy and enhancing for the mind and body, but what about my soul? The Rebbe’s words about each Jew being an emissary of G-d in the world, at every moment and at every stage of life, were shadowing me. My deeper questions were existential and spiritual.

I thought about the Rebbe’s words again as I contemplated how to celebrate the actual day of turning seventy, which I was rather dreading. And there was a further connection: my year of turning seventy fortuitously coincided with the seventieth anniversary of the Rebbe’s having assumed leadership of the Chabad movement. What advice would he have given me? And what would he have told everyone today about how to celebrate his own special “seventieth anniversary”?

So I read the transcript of the talk that he gave on his seventieth birthday in April, 1971. And here it comes: most important, he said, is to ask yourself on a birthday, “What have I done so far with all the days and years of my life since my coming into the world?” Am I like Abraham whose later years the Bible describes with the phrase “ba bayamim” (Genesis 24:1)?

That Hebrew phrase—ba bayamim—literally means “come into days.” It is often dispiritingly translated as “advanced in age” or “stricken with years.” According to the Rebbe, the Zohar interprets the phrase to mean that not one day is “missing” in your life; each one is full and meaningful. On his seventieth birthday, the Rebbe was asked whether he would now be taking it easier and slowing down. His answer? He intended to found seventy-one new Torah institutions in the next year, and asked his Chasidim to help. So he would not have let me off the hook. I also have to be able to “come into my days”—not just “fill my time” with a bunch of “hobbies” and activities. “Retired? What does that mean?” the Rebbe once asked someone in a private audience. There may be new situations requiring changes and adjustments, but “Retirement? Never!”

The Sweetness of Seiva; the Strength of Seventy

For a while, I toyed with the idea of trying “seventy-one new things” in the year after my seventieth birthday, like touring seventy-one new places in Israel. But that felt like too much, especially since my current levels of energy and stamina aren’t what they used to be. Indeed, I have more physical aches and pains than when I was younger, do not remember names as quickly. I no longer have the patience or will to sit day and night writing academic books. At the same time, I have felt other kinds of strengths growing inside—quieter and less visible.

In mapping the stages of life, the ancient Jewish Sages said: “Sixty, for sagacity (ziknah). Seventy for elderliness (seiva).” The word ziknah, used for the decade I just left—the sixties—is often literally translated as “old age.” The Talmud more profoundly translates ziknah as “sagacity”—defining ziknah as an acronym of the Hebrew phrase “zeh shekanah chochmah” or “one who has acquired knowledge/wisdom” (Talmud, Kiddushin 32b).

But I wonder, how is the sixty-year-old’s “wisdom” different from the seventy-year-old’s “elderliness”? What has changed? Is it all downhill from here? The question arises especially when I look at the English translations of seiva and find: “hoary head”; “gray-haired”; “elderly, aged.” Me?

Another place the Torah uses the word seiva is in the well-known commandment in Leviticus 19:32: “Mipnei seiva takum v’hadarta pnei zaken,” usually translated as, “Before the elderly person you shall arise, and honor the face of the old person.” Here in Israel, I smile when seeing the first part of that verse on stickers on public bus windows right behind the driver. “Mipnei seiva takum”: get up and give your seat to an elderly person. But now it’s started happening to me! Why all of a sudden are these young people getting up for me? Do I look old, weary, and weak? It wasn’t too long ago that I myself was giving up my seat for older people. On the other hand, I have to admit, it is a relief to get that seat.

In addition to getting relief on a crowded bus, I need to know what might be positive about seiva and what defines it. In an aside at one of my Torah classes, my long-time teacher fortuitously threw out a definition based on the words of Rabbi Yehuda Loew, the Maharal of Prague (1520-1609): up to the age of sixty-nine and including that year, you are considered ben olam ha zeh; you belong to “This World.” And when you turn seventy, you become ben olam ha ba—connected to the “Next World,” the “World to Come.” That was unsettling to hear. I wondered: Do I now have one foot out the door of this life, G-d forbid?

But then the rabbi continued. At age seventy, he said, you have amassed a huge amount of life-wisdom or “hochmat chayim.” You now see the world at large and your own personal life journey—all the twists and turns, ups and downs—with a very broad perspective. Until the age of seventy, it is not possible to have that wisdom. And that is why we rise for an “elderly” person. Mipnei seiva takum: the Bible uses only the word seiva here, he stressed, without any other descriptive adjective. It doesn’t matter if the seventy-year-old person is intelligent or unlearned; religiously observant or not; non-Jew or Jew; “butcher, baker, or candle-stick maker.” You are commanded to honor that life-wisdom of seiva. And for that we stand up.

I do feel that reservoir of life-wisdom welling up inside. It’s quite different from my academic intellect. But it, too, has been won through much toil and many tears. In my experience, that life-wisdom is about having more equanimity when looking at the world, at others, and at myself. More acceptance, more gratitude, and more humor about it all. It’s being able to more sweetly flow with the onrushing stream of life. That’s the wisdom behind the popular contemporary Israeli slang word—zorem—“flow”—meaning the attitude you need to get you through frustrating situations. At sixty, I was still immersed in and at the peak of my academic career. At seventy, I have more distance; I feel freer from all that. “Been there, done that.” Other things seem more important than adding to my CV. I feel more the need to nurture and support the younger generation, and myself, than to compete or hang on to what my professional status was at sixty.

But I confess, it is not easy to let go, be humble, and admit my energies and interests are just not the same. It is a loss as well. Maybe that’s what the mishnah is also adding when it distinguishes between the “wisdom/elderliness” of ziknah at sixty and this seiva of seventy. It is telling us that it’s a trap if you try to stay at seventy what you were at sixty. You will get stuck; you need to flow (“zorem”).

This is the way the book of Psalms (92:14-15) describes a person who has “flowed,” lived and aged well from age to age, stage to stage: “The righteous person flourishes like a palm tree; grows like a cedar in Lebanon. Those who are planted in the house of G-d shall flourish. They shall still bear fruit in seiva; they shall be fresh and flourishing.” Inspired by that, and a line I have always loved from Shakespeare’s King Lear, “Ripeness is all,” I now prefer to translate the word seiva as “ripeness.” Like a fruit from that date palm tree that has taken a long time to mature and grow, reached sweetness and wholeness. These lines also imply that seiva is not static; it has a special quality of generativity. Like the ripe fruit, whose purpose is not to drop off the tree and be done (“retire”), but to nourish, give forth further seed and generate more life. Seiva, in other words, is a power.

And that, as I happily discovered, is precisely how the Rebbe interpreted the words mipnei seiva takum,“before the elderly you shall arise,” in a 1982 talk on the seventieth anniversary of a Chabad yeshiva’s founding. The Hebrew grammar and syntax of the biblical phrase—and the Chasidic perspective—enable him to translate and interpret as: “Because of seiva, you will rise!”

In other words, the seivah itself creates the arising–the ascent to a higher level.

But what if, at age seventy, you look back and see some weakness or something that was missing from your life and your spiritual work during those preceding years? Again, the Rebbe does not let us off the hook: If so, then seventy becomes a time to begin anew with the extra strength now given you.

Eighty and Beyond

In sum, seventy years marks a level of shleimut, wholeness, in human life: you reach a special stage of holiness in your ongoing spiritual work of refining yourself and the world around you.

And then what? “Seventy years is the span of our life and given the strength (im b’gevurah), eighty years,” says the book of Psalms. Having celebrated my seventieth birthday last fall, I am actually now into my seventy-first year—the next decade—and so moving on already to eighty.

Ah, math can be so cruel. At first, I thought that this line from Psalms meant that with some extra luck, energy, and health, I might hang on another ten years and make it to eighty— but who knows in what condition. But then the Rebbe came to my rescue: the verse, he commented, is in fact giving you directions about what to do when you reach seventy. It’s telling you that after you complete that first seventy years, you then begin a whole new era of strength, of “gevurah.” You’re now coming to an even higher level of wholeness. And you now have the strength to overcome (hitgabrut) nature and limitations of the body. That itself is a kind of geulah, redemption, leading you and the world higher.

A young former university colleague ran into me recently and said with a quizzical look on her face, “You are the happiest retired person I know!” She couldn’t understand it, just as I wouldn’t have been able to at her age, or even a few years ago, until I began to live and work through it. I told her I don’t consider myself “retired” but rather “re-engaged.” During my official working years, I had to “retire” from so many things that I wanted to do, but for which I had no time. I’ve now entered a whole new era of strength and growth. I’m discovering the beauty of G-d’s world in a whole new way, developing new sides of myself that have yearned for expression. It was actually a great blessing that the University made me retire at age sixty-nine. I’m grateful.

Then I laughed—and remembered the famous description of the Woman of Valor in Proverbs 31:25, “She will laugh on the last day.” Laughter indeed comes from that larger broader perspective we attain at seventy. You look back at so many past events from your life that were so full of difficulty at the time, and now you laugh. And so also, the Torah tells us, on the great day of Redemption, “Our mouths will then be filled with laughter, and our tongues with songs of joy. Then shall they say among the nations, G-d has done great things for them” (Psalms 126:2). May we all stay “forever young.”

This essay is dedicated to the blessed memory of Rabbi Binyamin Klein, beloved secretary to the Lubavitcher Rebbe, whose love, laughter and wisdom comforted, enlightened and gladdened everyone.

Blumah Wineberg

BH wow professor susan handelman what an awesome essay! Thank you for your i sight and expressing so clearly the stages of life and the Rebbes fresh perspective which brings value to every day and every decade of life granted by Gd. May you continue to grow from strength to strength! Blumah wineberg