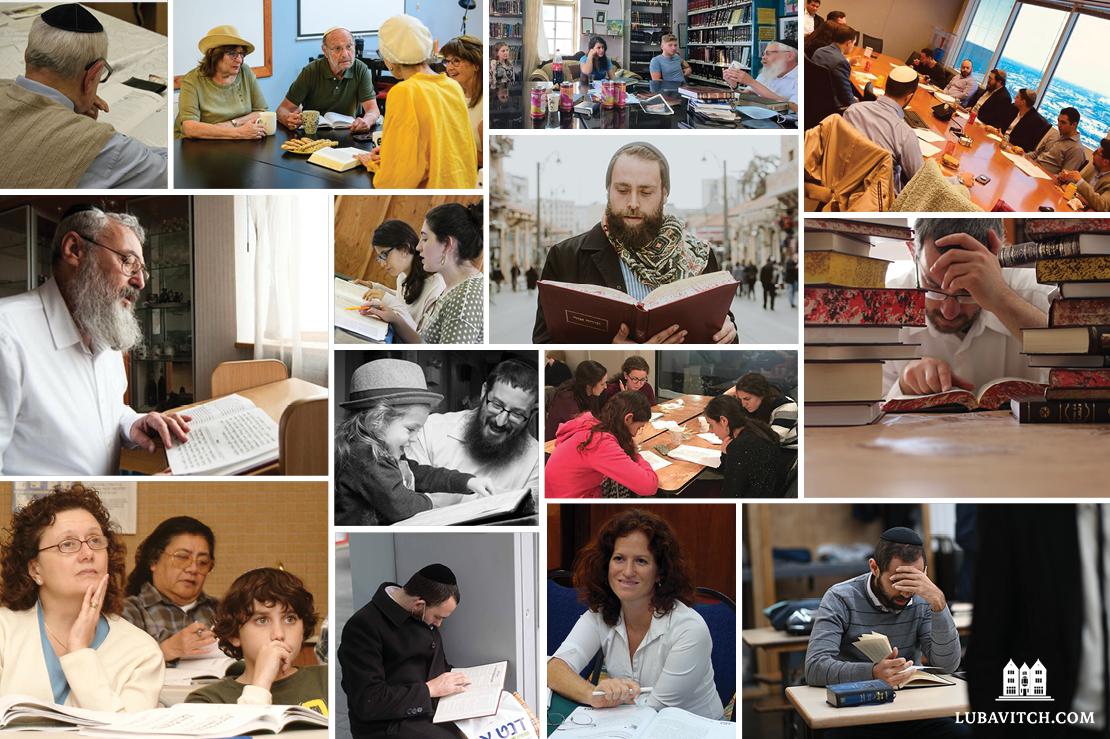

Want to study Talmud but never got a handle on Aramaic? No problem. Want to join adult Judaic classes but don’t live near a teacher? That’s not a problem either. What was once the province of an elite few is now available for free online in every language, and fifty years after the Rebbe initiated a campaign to bring Torah to the masses, adults of every demographic are cracking open the books and learning as never before.

On any given Thursday, my father-in-law, Dr. Ranon Udkoff, can be found hiking the Santa Monica Mountains near his home, reveling in the beautiful vistas while listening to a Torah podcast on his iPhone. Recently, the physicist and radiologist enjoyed “Prophecy or Pentium,” which explored how ideas like unified field theory dovetail with monotheism.

Looking down at the communities of the Conejo Valley below him, he points out a local school and laughs. “We moved out of Los Angeles to this neighborhood thirty years ago so we could send our kids to the local blue-ribbon schools,” the seventy-two-year-old notes. “We stayed, but we never enrolled the kids.”

For most of his early life, Udkoff considered himself a secular Jew and dedicated himself to academic fields, earning a Ph.D. in physics before becoming a physician. It was only after moving his family to the suburbs in the early 1990s that he began exploring his Jewish heritage. After seeing their children thrive in a local Jewish day camp, he and my mother-in-law, Dr. Rivka Udkoff — a fellow physician to a celebrity clientele in Beverly Hills — made the spontaneous decision to send their children to Jewish day schools. It was the first time the couple studied Torah in earnest.

Recent years have seen a renaissance of learning, with the founding of hundreds of yeshivahs for men and women, the publication of Jewish texts in dozens of languages, and an explosion of digital media covering the breadth and depth of Torah tradition. Udkoff joins thousands of Jews who have, in adulthood, realized a newfound desire to study the Torah and find their own place in the vast world of Jewish scholarship.

Taking Ownership

In the spring of 2020, as the sphere of in-person experiences contracted, Jews began looking for meaning in digital spaces where they might not previously have ventured. The popular Torah website Aish.com began posting on TikTok in 2021 — by the end of the year, they had 10,000 followers. Many sought to deepen their engagement at the organization’s flagship institution for adults in Jerusalem, says Aish’s CEO, Rabbi Steven Burg: “Enrollment in the yeshivah has skyrocketed in the last five years. The rise in antisemitism around the world is clearly making people reevaluate their ideas of Jewish identity. And the pandemic — the sickness and death people have witnessed — has awakened many to reevaluate their spiritual priorities.”

Yeshivah-style learning, which entails rigorous study of original texts, often with a study partner, may seem a far cry from thirty-second TikTok teasers. But for those searching for meaning and identity, it’s a natural progression, says Hadassah Shemtov, director of the Batsheva Learning Center, which provides advanced study opportunities for adult women online and in person in Brooklyn, New York. “To be an active participant in the learning process, discovering your own meaning in the text, finding your own resonance with what it’s saying — it’s hard to even imagine until you’ve done it. It’s the difference between watching a sports game and playing yourself.”

Yeshivah-style learning, which entails rigorous study of original texts, often with a study partner, may seem a far cry from thirty-second TikTok teasers. But for those searching for meaning and identity, it’s a natural progression.

For adults whose secular education far outpaced their knowledge of Judaism, it can be a revelatory and empowering experience, Shemtov adds. “Having an opportunity to explore the rich complexity of Torah and the halachic system gives people a sense of how sophisticated their heritage is.”

Udkoff attended Hebrew School on Sundays as a child in Whittier, California, but he came away with the impression that Torah was a “great set of stories with morals” rather than a spiritual or intellectual pursuit. His foray into Torah study began with Jewish lectures and books that spoke to his scientific sensibilities.

“I was skeptical of what I, at the time, considered mythology. I wanted to learn how Jewish beliefs reconciled with scientific principles such as evolution or the age of the Earth,” he says. He sought out Torah teachers with scientific degrees as he struggled to find his footing in a new world of learning. Luckily, his local Chabad emissaries were able to make the necessary connections, inviting Torah-learned scientists for Shabbatons and opening the floor to debate.

Let’s Learn

Today, Chabad is synonymous with Jewish social, humanitarian, and spiritual outreach. But it was founded as an intellectual gateway to Judaism and Jewish experience. That original mission is reflected in its name — an acronym for the Hebrew words Chochmah (wisdom), Binah (comprehension), and Daat (knowledge) that Chabad has sought to make accessible to all.

In the winter of 1971, the Lubavitcher Rebbe launched a far-reaching initiative to bring the mitzvah of daily Torah study to every Jewish individual — businesspeople, activists, stay-at-home parents, college students, and even children. This was not about Jewish literacy or language skills, the Rebbe emphasized, but rather about uniting the Jewish people in the daily act of engaging with Divine wisdom. The Rebbe’s enthusiastic young emissaries, famed for offering “mitzvahs on the spot for people on the go,” were now charged with extending Torah scholarship to the layperson.

In the pre-internet age, libraries of Jewish books needed to be trucked in from New York. English translations were hard to find, and those available were written in convoluted jargon. (Udkoff jokes that the rendering of tefillin as “phylacteries” was not very helpful: “Either way, I didn’t know what you were talking about!”) Translations into other languages commonly spoken by Jews, such as Russian or French, were almost non-existent.

When Rabbi Moishe Traxler moved to Texas forty-two years ago, he was fresh out of the Central Yeshiva Tomchei Tmimim Lubavitch. After years of studying Talmudic debate, legal deliberations in halachah, and esoteric Chasidic discourses, he was ready to teach.

With none of the sophisticated resources available today, Traxler would sit down one on one with anyone who wanted to know more about Judaism. “When we gathered enough of a crowd interested in a topic, I started a class. It was very organic and informal.”

In true Chabad fashion, one of the first formal groups the rabbi established, in 1980, was a Tanya class. The classic volume of Chabad Chasidut is a dense read on the intricacies of the soul, and is laden with references to other Jewish works. (Its first word, tanya, is a term used for quoting a Baraitic source.) Not exactly Judaism for Dummies. But Traxler, now Director of Chabad Outreach of Houston, refused to offer the CliffsNotes version. “My students were interested in engaging with the text and raising their level of awareness. You only get that through authentic Torah,” he explains. “Torah does not need any background. You can start anywhere and build from there.”

Arthur Corenblith struggled with some of the classic questions about G-d when he was growing up in the heart of Texas. “Why did good things happen to bad people? How could G-d let the Holocaust happen?” the former footballer and schoolteacher recalls asking. “I was very resistant to many of the Jewish practices I saw around me. I could not believe how much people followed without questioning.”

The Houstonian wandered in and out of Jewish social settings throughout the years, but never received a formal Jewish education. Ten years ago, Corenblith attended his first Torah class at a friend’s house. Rabbi Traxler was teaching a course on Jewish giving. “It seemed a bit ridiculous to me that there was an entire book just about giving: when to give, how to give, giving anonymously, ” Corenblith says. Yet, something about the class stuck. “Years later, I would encounter these scenarios that the class was talking about, and I saw the wisdom in the rules, like, ‘If you want to give, give right away.’ The teachings mattered.”

Being able to finally ask questions openly and receive satisfactory answers was cathartic for Corenblith. “I finally understood some of the Jewish practices—what they mean and why we do them.”

Mrs. Malka Touger, a renowned Torah teacher, lecturer, and author, is careful to distinguish the study of Torah from other academic disciplines.

“Classic academic study lends itself to different interpretations. Someone presents a theory, another negates it, and so on,” she explains. “With Torah, we are not looking to put ourselves in the picture. We try to penetrate the text and squeeze out everything it has to offer.”

Touger’s favorite subject to teach is Tanach, the canonical collection of the Five Books of Moses, Prophets, and Scriptures. And she often chooses the more provocative stories of the Bible: Sarah banishing Hagar, Judah and Tamar, Joseph’s delay in revealing himself to his brothers.

“There is a challenge in how to perceive biblical characters,” she says. “We do not necessarily view them as infallibly holy, yet the text itself is sacred. My goal is to help develop a way of understanding an ancient and spiritual people from a contemporary perspective.”

In the pre-internet age, libraries of Jewish books needed to be trucked in from New York. English translations were hard to find, and those available were written in convoluted jargon.

The key, she recommends, is to allow the learner to dissect and grapple with the actual texts. After a cursory look at the stories, Touger’s students delve into the layers of symbolic, midrashic, and kabbalistic commentaries, weaving in context from across the twenty-four books of Tanach.

“By capturing the whole scope of Torah, students begin to understand that there is a thread throughout all of Judaism’s written and oral tradition — and that it is all Divine,” Touger says.

Like Diving into an Ocean

For a period in the mid-’90s, Udkoff became interested in “Torah Codes” a then-trendy area of study that finds words or messages in equidistant letter sequences in the Remez tradition of biblical exegesis. Jewish hermeneutics incorporates four levels of study: Peshat — literal interpretation; Remez — typological or allegorical interpretation; Derash – apocryphal; and Sod — mystical interpretation.

“I read studies by statisticians who ran the numbers, and the chances of repeatedly finding meaningful words and messages in the Hebrew text were statistically unlikely,” the physicist says. “My appreciation for the spirituality of Judaism was increasing.” He kept signing up for classes, partially motivated by his feelings of incompetence in helping his children with their Judaic homework, but also because “the more I learned, the more I realized how much more there was to learn.”

Adam Spiro had a similar experience. Raised in a traditional Jewish family in Montreal, Spiro attended a secular Jewish school that taught Yiddish as part of the curriculum. But the formal Jewish education was superficial, he says. After graduating law school, he sought out Chabad to learn more about Judaism. At first, he resolved to pace himself: “Starting to study Torah can be overwhelming. I told myself that I wasn’t going to go crazy. I committed to learning the text of the week’s parshah in English every week.”

The desire to limit his Torah learning didn’t last long, Spiro says. “I couldn’t keep myself away.” Chasidut, in particular, struck a chord, as he found meaning and inspiration in the esoteric realm of Jewish thought. “A Chabad friend told me that Yaakov Brawer [professor emeritus at McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine, who lectures on neuroendocrinology and Chasidut] was giving a class at the local Chabad yeshivah,” he says. “I showed up in my pink shirt and tie and sat among the seventeen-and eighteen-year-old students to listen to the professor’s lecture. Most of it went way over my head, but the five percent that I did understand was enough to keep me coming back for more.”

Bringing the Book to the People

From the Talmud’s Aramaic to Me’Am Lo’Ez’s Ladino, and from Reb Saadiah Gaon’s Arabic Tafsir to Tze’enah Ure’enah in Yiddish, the Torah has long been translated into the Jewish vernacular of the day. In recent times, the Anglo-Jewish world has been enriched with a wealth of excellent translations of classical texts into modern, readable English. The publication of the Schottenstein Talmud in 1984 was a pivotal moment. The Steinsaltz Koren Talmud Bavli followed in 2012. There are translations of Maimonides, biblical commentaries, Kabbalah, halachah, and more new releases daily.

Rabbi Mordechai Dinerman, co-director of the curriculum department at the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute (JLI), says that Judaism has a long tradition of finding ways to make learning more approachable. Historically, it was the great scholars, he observes, “from Maimonides to Rabbi Yosef Karo, who did the work of accessibility.”

A famous example is Ein Yaakov, the sixteenth-century compilation of (Aggadic) non-legal, narrative literature from the Talmud. The work was specifically compiled for those who lacked the schooling to access the more difficult parts of the oral law.

In our own day, numerous educational programs and publishing houses have been similarly dedicated. Within Chabad, the Jewish Learning Institute is one such successful initiative. Established in 1998, JLI offers an expansive adult-educational program reaching thousands through Chabad Houses around the world.

After its research findings showed that 82 percent of the Jewish community is interested in medicine, law, finance, or psychology, JLI developed a curriculum to match. “Our courses meet people where they are, and allow them to appreciate the profound relevance of Torah to their real lives,” says Rabbi Efraim Mintz, JLI’s executive director. The courses are respectively accredited by academic organizations like the American Medical Association, the American Bar Association, and the American Psychological Association.

The categories seem to work. Udkoff is interested in medicine, Spiro in law. Eliza Hirsch, a fifty-one year-old mom of four, is interested in psychology. Hirsch started learning about traditional Jewish observance in her teenage years, but says she was “mostly winging it.” At twenty-nine, she began studying Torah.

Hirsch studies Chumash and Talmud at Chabad’s Montreal Torah Center. “The language has always been a barrier for me,” she says. “In the course of study, I am constantly encountering new terminology and writing down Hebrew words to translate.” Reading direct English translations of classical texts does not quite solve the puzzle, she explains, as the very words themselves contain intricate layers of meaning — core teachings, and even legal rulings, are often derived from the root of a Hebrew term or an odd wordplay.

But Hirsch savors those aha moments when she deciphers a previously incomprehensible section of text.

In the winter of 1971, the Lubavitcher Rebbe launched a far-reaching initiative to bring daily Torah study to every Jewish individual — businesspeople, activists, stay-at-home parents, college students, and even children.

“The concept that the Torah is a living, breathing entity that you can always learn more from really resonates with me,” she says. “For twenty-three years I have been learning parsha weekly, and every year I learn something new. More than anything, Torah enables me to connect to G-d and have a purpose.”

The internet has democratized Jewish learning like never before, with almost infinite opportunities for learners to engage in every area of Judaism as actively and as autonomously as they wish. In 1988, when cyberspace was still in its infancy, Chabad.org was founded as the first online destination for Torah learning. Today, it is the world’s largest faith-based website, with 54 million unique visitors last year. The site boasts over twenty-thousand multimedia titles, from children’s entertainment to in-depth Talmud study. And the numbers grow daily.

Rabbi Traxler has observed the advances in Torah access with delight. “The people who used to come to me with basic questions are now showing up in shul with a dvar Torah they pulled straight from Chabad.org,” he says. “Anything you want to learn you can now learn online; with rare Jewish books you cannot get anywhere else.”

Technology has also made yeshivah-style learning more accessible. JNET — Chabad’s Jewish learning network — matches individuals for one-on-one study via phone, WhatsApp, Zoom, FaceTime, and Google Meet.

“The web has been an absolute game changer,” says Rivka Slonim, Chabad emissary to Binghamton University, who has been teaching Torah for nearly four decades. “During the height of the Covid shutdowns, it was breathtaking to see everyone suddenly teaching online. There were live classes at any hour of the day. It seemed that the whole world had become one big classroom.”

But, she cautions, “Information is not the same thing as wisdom.”

“There is an information glut out there that can be hard to navigate,” she says. “Yes, one can finally read and access the texts easily. But you cannot separate Torah learning from its practice. Ideally, Torah needs to be learned with someone who can communicate its applicability to real life.”

No More Excuses

In a 1991 conversation with Baila Olidort following the publication of his first translation of the Talmud into Hebrew, the late Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz offered a similar insight:

“I have not popularized the Talmud in the sense that it is easily read. The Talmud is written in its own jargon, which limits its accessibility. So I wrote it in a language that is accessible. But it cannot be made into ‘light’ reading material. . . .

“It is certainly a tough book. It is not easier than any book on mathematics, law, philosophy, or a combination of these. And one cannot merely read it, but must study it and be involved with it if he or she is going to accomplish anything. And although I have made this a possible task now, it still entails a fair amount of involvement, possibly a teacher, a teaching community, or at least a study group to do it properly. As somebody said when the first volume appeared in Hebrew: ‘From now on, we no longer have a good excuse to be an am ha-aretz — an ignoramus.’”

Udkoff agrees. There are no more excuses. He has experienced what he describes as a “slow, exponential change” in gaining knowledge and comfort around Torah learning. He regularly attends online Torah lectures, listens to Jewish podcasts, watches YouTube Torah tutorials, and enjoys email correspondence with rabbi-scientists in the field. “In my lifetime, I have seen the access to Torah greatly increase. My inbox is full of Torah newsletters and options to sign up for this or that class.”

Udkoff is now planning to enroll in an online course for smicha, rabbinical ordination. He will lean heavily on the digital resources available to him but admits that, when it comes down to true textual analysis, nothing beats sitting down for a one-on-one book-in-hand session with his favorite study partner — his son, a yeshivah graduate. “The rabbis got something right with chavrusa learning [the tradition of studying in partners or small groups]. It brings me back to my college days — breaking down, analyzing, discussing, and debating a shared text. There is really no more satisfying feeling in the world.”

This article appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of the Lubavitch International magazine. To download the full magazine and to gain access to previous issues please click here.

Lea Chaja

It is a pity that I have to translate everything from English into Polish

Zevi

Please get back to me. I’m looking for someone to teach me gemarah. My name is Zevi and my telephone number is 646 737 6747 and my email is Financ71@gmail.com.

Thank you