Four days a week, Zippel drives across Utah’s sometimes treacherous terrain, visiting 100 Jewish adolescents. They are 10-18 year olds, each facing their own struggle: drug abuse, violent behaviors or eating disorders.

In 1996, a young rabbi walked onto the grounds of Youthcare, a residential treatment center for troubled teens in Provo, Utah on a mission. He was looking for a certain Akiva Greenfield*, a gangly Israeli teenager. When he finally found him, the smiling rabbi introduced himself.

Rabbi Benny Zippel from Chabad wanted him to know that he had a friend in Utah. “If there is anything I can do for you while you’re in here, please let me know. When they give you the ok, I’d like for you to come visit me for Shabbat.”

With the simple invite, the rabbi threw a lifeline to the struggling young man whose troubled journey landed him far from home and family. At 14, Akiva had dropped out of his yeshiva high school, moved in with his girlfriend, and started smoking, drinking and using recreational drugs. The son of a respected rabbi and teacher in Jerusalem, he grew up in what he describes was a loving home.

As he continued to spiral out of control into more dangerous behaviors, his parents and teachers were unprepared for his teenage rebellion and despaired of getting him back on track. Akiva’s father enlisted the help of an educational consultant who specialized in teenage behavioral disorders. He flew with his son to the United States and began a long state by state search for the kind of residential center that Akiva needed.

A rehab program in Minneapolis was a first address, but after Akiva ran away, his father hired a crisis intervention transport service to transfer him to Youthcare in Provo. Finding himself in the middle of Utah, the young Israeli felt disoriented. “I felt like I was on another planet, on the moon,” he recalls. Akiva refused to participate in the program’s services. He remained in isolation, biding his time until, he hoped, “they’d figure this all out and let me go.”

They didn’t. Akiva dug his heels in and refused to cooperate. But he perked up at the sight of the Chabad rabbi. “It was like a mirage–a rabbi in the middle of nowhere, Utah, looking for me!”

The visit gave the teenager hope. “I was in a place where I did not belong, and here was this flavor of home, an instant connection to hang onto.” Hoping to earn the privilege of an off-campus Shabbat visit, Akiva finally felt motivated to push forward on the long road to healing.

Jewish Kids in Mormon Country

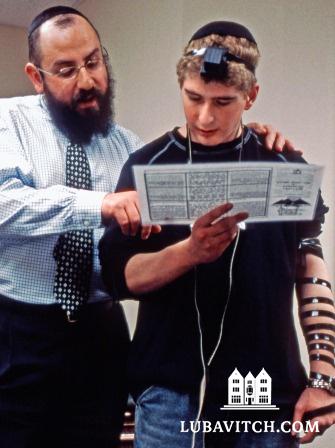

Four days a week, Zippel drives across Utah’s sometimes treacherous terrain, visiting 100 Jewish adolescents. They are 10-18 year olds, each facing their own struggle: drug abuse, violent behaviors or eating disorders. He spends an hour or two with the kids, studying Judaism, celebrating an upcoming holiday or simply chatting.

Zippel’s two decades of involvement with Jewish teens at risk evolved from a phone call he received from a concerned father in Southern California, shortly after he and his wife set up their Chabad House in Salt Lake City in 1992. The man asked Zippel if he would visit his teenage son who was in school in Utah, and help him celebrate Chanukah. “I wondered what a Jewish teenager was doing in school in the heart of Mormon country,” says Zippel. But he packed a Menorah, some latkes, Chanukah gelt, and dreidels, and happily obliged.

The visit opened the young rabbi’s eyes to the world of residential treatment centers, known among social workers as RTCs, that provide live-in therapy and behavior modification exercises for adolescents. RTCs proliferate in the Beehive State–there are 47 NATSAP (National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs) centers today because it is one of the very few states that allows a parent to send a minor child to an RTC without his consent. Zippel soon realized that the boy was only one of dozens of Jews in the school, with many more in similar institutions nearby.

“As I looked into it further, I began receiving more calls from concerned parents across the U.S. and even abroad.” This demographic in dire need of Jewish education, inspiration and friendship, became a priority for the Chabad rabbi. “I started reaching out to different treatment centers to volunteer my services to their Jewish students, and it snowballed from there.”

Now, 24 years later, the visits have become a program known as Project HEART, Hebrew Education for At Risk Teens, providing counseling to hundreds of young people in therapy at more than two dozen treatment centers across six counties. Over kosher snacks, the rabbi engages the teens in informal discussions about Judaism and their lives, developing a personal bond with each one.

Embracing Purpose, Meaning

While RTCs may provide a setting where love, care, and therapeutic rehabilitation are readily available, there is little in the way of spirituality. But, says Tami Harris, a spiritual chaplain at Heritage Schools where 10 percent of the student body is Jewish, it helps for students “to know that they aren’t in this alone, that G-d has not forgotten about them.”

Spirituality, Harris insists, is as important to the healing process as any other component. “We meet their mental, emotional, social, and physical needs, but if we forget the spiritual piece, our students are not going to be as balanced or as healthy as they could be.”

Zippel’s outreach is inspired by the Rebbe. “I share with these kids what the Rebbe saw in every person–the divine spark within. He gave each individual, no matter what background or affiliation, the chance to tap into that divine spark, and use it as a catalyst for individual self-improvement and self-actualization.”

With the caveat that he works as a volunteer and not as a certified mental health professional, his involvement as a non-professional, he says, works in his favor. “When kids are with me, they make the distinction that they are not in therapy. They are not being analyzed or scrutinized. They are being loved.”

Zippel’s message has a profound effect on the teens, Harris observes. “It allows each of these young people to acknowledge and come to terms with the wealth of goodness that exists within them.”

Healing Relationships

At the early stages of his stint at Youthcare, Akiva was still too angry to speak with his parents. That would change over time, with the help of Zippel, who Akiva saw as a “warm and loving holding space,” there for him as he tried to take stock of his life and make changes.

“I knew what I did was bad. But here was one person who could see my strengths, and who acknowledged me for what I can do and not for what I have done,” Akiva says. “I really appreciated the unassuming, non judgmental nature of our interactions, and Rabbi Zippel’s easy acceptance of who I was.”

Teens at risk will sometimes have a complicated relationship with Judaism, tied in with feelings of anger, guilt and rejection. The positive attitude of an easy-going rabbi who embraces them as individuals, and supports them in their own self-discovery as Jews, makes it possible for them to relate to their place in the Jewish community with self-confidence.

When his good behavior finally allowed for off-campus visits to the Chabad House, Akiva experienced his first moments of unsupervised freedom. He spent several weekends with Zippel, his wife, Sharonne, and their kids. “During some of the roughest moments of my life, they just made it warm and human and Jewish. That was home.”

The Parent Link

Parents dealing with a child’s emotional disorders usually come to Zippel desperate. Facing the unknown, their worst fears are suddenly realized. “Sometimes parents call me after their kid was released from a local psych ward, or comes home at three a.m. stoned, or refuses to go to school, wondering where they have gone wrong.”

That is how Josh and Debra Segal felt when their 16-year-old son Jacob began refusing to go to school two years ago. “He turned belligerent, and nothing was progressing in a positive manner,” Debra says. Willing to try anything, the New York couple began looking into a Utah wilderness therapy program, a 10-week outdoors program that integrates wilderness skills with intensive therapy.

Early on in their research, the program put them in touch with Rabbi Zippel, who walked them through the crisis. A reassuring voice to parents during this difficult time, he reminds them that “It’s not something bad that they have done or not done. Some of these kids come from the nicest and finest families.”

Moving On

After six grueling months in Utah, Akiva returned to Israel, reconnected with his family and his faith, completed his military service in the IDF and got a postgraduate degree. Today, 19 years later, the 35-year-old lives in Jerusalem with his wife and three children, with a successful career as a clinical social worker that specializes in adolescents. And he stays in touch with the Zippels, visiting the family periodically.

Like Akiva, many of the teens Zippel has worked with return home and reconcile with their parents, go off to college or yeshiva, get married, and build wholesome lives. While some want no reminder of those difficult years, many keep in touch with the winsome Utah rabbi who won their trust and gratitude.

“I had the blessing of having the right guy come into my life with the right attitude at the right time,” Akiva says. “Rabbi Zippel had the human intelligence to give me the exact moral support I needed in a subtle and warm way. The way he made his way into my heart was an act of genius.”

*The names and some identifying details of families and teens in this story have been changed to protect their privacy.

Be the first to write a comment.