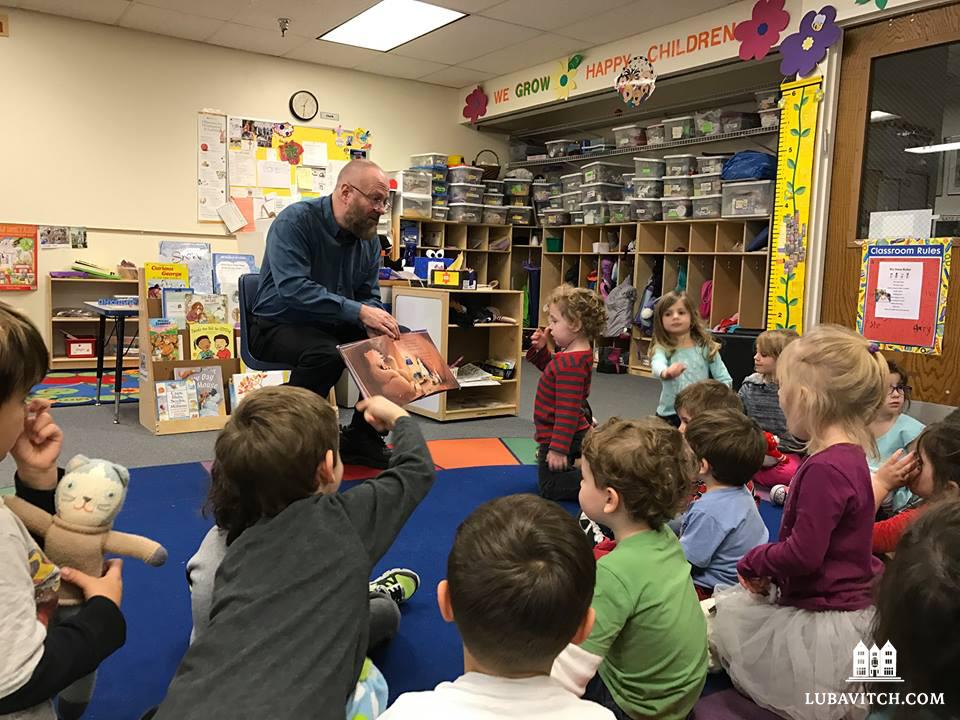

Some thirty children arrive every morning to the Gan Yeladim Jewish preschool in Toledo, Ohio. Mrs. Raizel Shemtov, a Chabad emissary to the city since 1987 and director of the preschool, has developed a holistic Jewish curriculum earning her rave reviews from parents and educators in the tight-knit Jewish community, and a five-star rating from the Ohio Department of Education.

Thirty children may seem a small number, but in a city of 2,500 Jews it represents nearly 100% of the Jewish preschoolers. Rabbi Yossi Shemtov, who directs Chabad of Toledo with his wife, is proud to be serving Toledo’s youngest Jewish constituents.

So is the Jewish Federation of Greater Toledo. The preschool’s $200,000 budget has become an item on the Federation’s annual campaign in a partnership formed after the 2008 recession. Until then, Chabad covered its own budget, but as funding dried up and fears that the preschool may have to shutter its doors became real, Chabad and the Federation broke the mold. Together, they formed an effective partnership that has since served Toledo’s Jewish community, making it a model of cooperation.

“It was mutually beneficial for both of us,” says Joel Markovich, the CEO of the Toledo Jewish Federation for the past four years, of the arrangement. In this partnership, the Federation would fulfill the preschool’s budgetary requirements, and Chabad would continue providing the city’s Jewish preschoolers with a high-quality early childhood education. “Our goals are aligned as we are both working to enrich the Jewish community of Toledo. It’s a win-win full partnership scenario.”

The partnership doesn’t end there. The Jewish Federation of Greater Toledo and supporting organizations in the Toledo Jewish Community Foundation host numerous projects jointly with Chabad, underwriting one third of Chabad’s Friendship Circle budget. It also sponsors full scholarships giving children an overnight summer camp at a Chabad-run Gan Israel—one of five camps that the Federation selected for its Jewish camp scholarship program.

An Evolving Relationship

The relationship between Jewish Federations in North America and Chabad Lubavitch centers vary from city to city where both exist. In some cities, like Toledo, Federations are responsive to Chabad’s applications for funding with generous grants that ultimately serve the Jewish community’s best interests. In others, the relationship is marked by tense coexistence, both working parallel to each other with no overlap.

In some smaller communities, collaboration and cooperation can be critical to survival. Shemtov says that it would be “impossible” for him to build and sustain first-rate institutions for his local community without the strong partnerships of other supporting organizations. And for dwindling Jewish communities in small towns with Jewish infrastructures that are downsizing or even dismantling, Chabad’s willingness to come, set roots, build, and stay where no others will, is a blessing.

Mrs. Chana Silberstein, a Chabad emissary to Ithaca, New York, recently served as a chair on the local board of the Ithaca Area United Jewish Community—a Jewish Federation equivalent in her small upstate New York town. While she appreciated the opportunity, she admits that her involvement was a factor of the city’s limited resources where “manpower is always appreciated.” Silberstein is careful to avoid generalizations about Chabad and Jewish Federations’ historically complex relationships, but has seen them evolve in some places where both have put differences aside to work together for the benefit of the community.

Peter Silverman, a business attorney in Toledo who played a key role in facilitating the partnership between Chabad of Toledo and the Federation, explains that when he helped negotiate the terms of the collaboration, “the first thing we needed to tackle was the emotional barrier.”

“Chabad can at times be unduly concerned that the other is ‘out to get them,’ while the Federation may feel threatened that Chabad is ‘taking over.’” Neither fear is completely unwarranted, given complicated histories in various communities. But by putting all concerns on the table, insists the lawyer, they could address and manage the issues, real or imagined.

Changing Times

“When we came to Toledo in 1987, our goal was to supplement and fill a void in the Jewish community,” says Rabbi Shemtov. Then the Toledo community was well established with 6,500 Jews, three synagogues and even a day school that has since closed. But as was happening in dozens of smaller cities across North America, the younger generation was fleeing to larger cities for economic and social reasons.

“We are a shrinking city,” admits Rabbi Shemtov. The decline he’s seen in the local Jewish population over the past three decades is unfortunate for these communities, but the upside, he says, is that many leave to larger cities for better access to Jewish life and Jewish education. They leave, but Shemtov’s family is staying put. In fact, his own daughter, Mrs. Mushka Matusof, settled in the city a few years ago to run the Friendship Circle and other Jewish youth programming.

And despite the changing tide, Chabad’s efforts are rewarded. The Toledo Friendship Circle welcomes 51 teenage volunteers from the Jewish community who befriend children with special needs. Toledo only has 135 Jewish families with children under the age of eighteen. Assuming a spread of age groups, Shemtov estimates that an overwhelming 50% of the city’s Jewish teenagers participate in the unique program.

The strong participation in Chabad-led activities is supported by numerical data in larger Jewish communities as well. In 2014 the Miami Jewish Federation published its once-a-decade population study, A Portrait of the Miami Jewish Community. The study showed that more than one-in-four Jewish households in Miami-Dade County—some 26%—have engaged in Jewish programming through Chabad during the past year, including 42% of Jewish households with children at home. Nearly half of all Jewish households led by people under age 35—some 47%—visited a Chabad center or participated in a Chabad-related activity within the past year. It was the first time the study calculated participation in Chabad as a measure of Jewish engagement (along with Passover Seders and having a mezuzah) and is a rare scientific look at Chabad demographic engagement. As South Florida boasts the third-largest Jewish population in the United States, these numbers reflect a dramatic shift in how Jews are choosing to engage.

Don Solomon, past chairman of the Toledo Jewish Community Foundation, commends both Rabbi Shemtov and Joel Markovich for the culture of cooperation they are modeling. “Because of the size of our community, it is absolutely necessary that the different Jewish organizations and synagogues here have a cooperative attitude,” Solomon notes. “It is a matter of survival.”

As CEO of his Federation, Markovich is very aware of the changing interests of his constituents. “If you look at the numbers across the board, membership in congregational life is down. Institutional-based organizations are not attractive to the millennial generation,” he concedes. In an effort to engage the younger crowd, his team has moved from institutional-based messaging to cause-based messaging. “We try to communicate what we are doing—feeding poor families, helping those with special needs. When people connect with a cause they care about, that’s when they engage.”

Chabad, on the other hand, was not founded as an institutional model. “They are way ahead of the Federation world in this shifting atmosphere. They provide service after service after service, drawing people in and engaging them in things that they connect with, and only afterwards ask the community to support it—after it’s already been proven to work and enhance their lives,” observes Markovich.

As a smaller Federation with more flexibility for change, Markovich is eager to innovate and experiment, like this unique strong partnership with Chabad, addressing and anticipating the needs of his community.

Charlotte, NC

Population trends moved in quite the opposite direction in Charlotte, North Carolina, where the Jewish community is growing. Rabbi Yossi Groner says there were 4,000 Jews in the city when he moved there in 1980 to serve as a Chabad emissary. Today, there are more than 18,000, a pattern in Southern US cities that have recently been attracting thousands of young professionals to their thriving business sectors, as well as retirees seeking warmer climates.

In 2016, the Jewish Federation of Greater Charlotte allocated $3,651,420 to beneficiary agencies ranging from the local day school to Jewish Family Services and children’s programs. Chabad of Charlotte received $10,000 for its Friendship Circle program, and $12,500 for its popular Uptown Chabad program that provides networking and Jewish connections for Jewish young adults. In Ballantyne, North Carolina, a suburb of Charlotte, the Federation helps fund a young Chabad center—the only Jewish destination in town.

Groner attributes the positive relationship to the personalities of the leadership. “The executive director of the Federation makes an effort to be inclusive,” the rabbi notes. “It also so happens that many of the lay leaders in the Federation are members of Chabad and support our prominent role in Jewish life in the community.”

Groner has even leveraged that relationship to benefit other Chabad centers. Charlotte is a sister city of Hadera, Israel. “When we discovered that they were looking for initiatives to support in Hadera, we approached the Federation leadership and suggested that they fund Chabad of Hadera’s activities.” For years now, the Chabad soup kitchen in Hadera has been receiving a check from Charlotte’s Federation.

Two-Way Street

Chabad emissary Rabbi Zalman Bluming, of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, believes that there is a seamless and natural partnership between the two umbrella organizations. “We both work under the open tent model, engaging every Jew regardless of background or affiliation. That attitude of openness and acceptance naturally lends itself to working together.”

Bluming often collaborates with the local Federation in North Carolina for major holiday events, and hosts his popular Chanukah and Purim parties at the Federation’s new $10 million campus. The rabbi’s JLI Torah classes are housed in the Federation building and the two organizations are constantly looking for innovative ways to partner and reach more Jews. The Jewish Federation of Durham-Chapel Hill recognized the Blumings this past January with the Earl and Gladys Siegel Young Leadership Award, a prestigious annual designation for those serving the local Jewish community.

Madeline Seltman, the director of engagement at the local Federation, says the couple deserved the award for “always doing what is best for the community.” Seltman echoed Bluming’s feelings. “Working with the Blumings is a pleasure since, unlike some other synagogues, Chabad and the Federation are open to anyone in the community regardless of affiliation.”

Edward Finkel is a Regional Director of the Network of Independent Communities at the Jewish Federations of North America headquarters in New York. “We work with over three hundred small communities throughout America,” he offers. The Jewish population of these communities range from 100-5,000 Jews, some as remote as Dothan, Alabama or Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Most without professional Federation offices or staff, “the engine of these communities is predominantly volunteer directed, and the local clergy play an important part.”

In many of these isolated places, the local Chabad emissaries may be the only ones offering Jews a Jewish connection, notes Finkel. It’s a fact that has made his team at the Federation appreciate the role that the emissaries fill. “Chabad is always there with an open door and open arms, bringing these communities a message of the beauty of Judaism and helping them educate their children and engage them in Jewish life. It is very holy and important work.”

For his part, Finkel sees a benefit to partnering with Chabad in serving these cities, especially given their size. “Chabad is integrated into the fabric of the Jewish community. Our role is to make sure we are responsive to them and make sure that they are connected with amcha, the broader North American Jewish community.” In practical terms, the JFNA office supports the work of Chabad not only in crisis, but in “good times” by helping them provide programming to their communities that act as a gateway to Jewish life.

Finkel describes a strong working relationship with Chabad emissary Rabbi Berl Goldman in Gainesville, Florida. With a Jewish population of 2,500, Goldman, says Finkel, plays a vital and dominant role interfacing with the Jewish community at large and reaching out to the student population at the University of Florida. The JFNA supports these successful efforts financially, making Goldman their “visible formal partner in Jewish life.”

And the Federation is also there to help small communities in times of need with emergency resources and “to make sure they are not alone.” When Chabad of Hoboken, New Jersey sustained heavy damage to their facilities during Hurricane Sandy, Finkel’s office stepped up to replace the Chabad House roof and kitchen equipment, assistance, he explains, that was necessary for the community. “We wanted them [Chabad] up and running as soon as possible so they could continue to serve meals on Shabbat and holidays to the Hoboken Jewish community.”

Rabbi Avi Richler, Chabad representative to Gloucester County, NJ, points to Finkel as an ideal, but rarefied model of healthy cooperation. “Mr. Finkel is an example of the kind of leadership I wish we would see more of.” Richler arrived in Gloucester County in 2007, when no one but Chabad showed any interest in creating Jewish infrastructure in a region that counted only 1,000 Jews and a paltry 5% engagement in Jewish life. But under Richler’s leadership, Gloucester County’s Jewish community has blossomed, growing in size and Jewish engagement by more than 25%. Today, Chabad represents all aspects of Jewish life in the county, including its own budgetary needs.

“There is no local Federation in Gloucester County, but the Federations in the neighboring areas have yet to recognize the dynamic position that Chabad has taken in leading the growth of Jewish life in Gloucester County,” says Richler. “I believe we could achieve so much more if we would cultivate a spirit of genuine cooperation and support.”

Jewish Continuity

With centers and representatives serving Jews in 90 countries around the world, and with the most human resources on the ground, Chabad arguably enjoys the widest reach in the Jewish world, prompting many Jewish agencies to partner with Chabad and gain access to its broad base.

Rabbi David Eliezrie, Chabad emissary to Yorba Linda, California, is convinced that a historic shift may be underway, with cooperation between Chabad and Federations becoming more prevalent overall. The rabbi, who also acts as Chabad’s liaison to the Jewish Federations of North America and sits on the Board of Governors of the Jewish Agency, says that “Chabad’s focus on Jewish education, tradition and values is what keeps Jews Jewish.”

“There has been a vast improvement in partnerships between Chabad and the Federation, but it is still a work in progress. In certain places, we see a cultural clash between the entrepreneurship of Chabad versus the committee and consensus-driven model at the Federation. Both organizations can gain from seeing the value in the other’s approach.”

In Long Beach, California, Chabad emissary Rabbi Yitzchok Newman sits on the Federation’s board as a Partner Agency Executive Director and has a say in the decision-making of the 20,000-strong Jewish community. Recently, the Federation started serving only kosher at all its major functions.

The rabbi is the Head of School of Hebrew Academy Huntington Beach, with 350 students. In addition, Chabad reaches more than 1,000 children each year through its camps and youth programming. The Federation acknowledges the enduring results of the successful school, which was founded in 1969, and has recognized that a large percentage of graduates remain actively involved in the local Jewish community. Many of the Federation’s board members are alumni of the school.

John Kaiser sits on both the Federation and Hebrew Academy boards, and is a past vice president at the Federation. “In my role as the chair of the allocation committee at the Federation, we realized the importance of the Chabad Jewish day school in our community. We realized that if we are going to have a continuation of Jewishness in our community, the local Chabad day school is probably one of the most prime areas of importance to us to fund.”

At the day school, Kaiser says he sees the results of this investment. “To me, the Chabad day school’s mission statement is so fundamentally philanthropic. It commits to educating any Jewish child who wants a Jewish education, regardless of financial circumstances. As a board member of the Federation that takes prime importance to me. I vote all the time to give more money to the school.”

Like Rabbi Richler in Gloucester, Rabbi Shaul Perlstein, Chabad emissary to Chattanooga, Tennessee, looks at these models with optimism. Tensions in the relationship between the Chattanooga Federation and Chabad have resulted in very limited cooperation to date, but, he says, he hopes that he and his counterparts at the local Federation will find a way forward so that they can work together to benefit the city’s Jewish community.

Jewish Fundraising and Giving: Enough to Go Around

Federation and Chabad sometimes see themselves competing for the same fundraising dollars, a sticking point for both. “It is difficult to negotiate when organizations feel that their funding source is threatened,” says Silverman. “But in some ways, the added competition is really just enlarging the pie. There is a large untapped element of the community that doesn’t give at all. By engaging and encouraging more people to support Jewish causes, all can be successful.”

Chabad and Federations raise funds for different projects, observes Markovich. “They are not a threat to us.” Recently, Shemtov raised over a million dollars for a new building campaign. “People were worried that it would impact our campaign, but we still met our goal,” says the Toledo Federation’s CEO. The Federation even saw a slight increase in the fiscal year that Chabad ran their campaign. “It is not ‘we raise a million, they will lose a million.’ The partnership is very complementary.”

Silverman saw the negotiating process as an opportunity to break down everyone’s concerns by talking through the issues, like who gets credit for a program, which programs can be used to solicit donations, when are appeals done etc. The nitty, gritty details of hard numbers and policies helped create a manageable partnership.

Another benefit many acknowledge now, in partnering with Chabad, is the quality and commitment of its human resources, particularly in smaller communities with a dearth of energetic young Jews willing to work in the nonprofit world. “Chabad is very willing to work 80-plus hours a week and put incredible dynamism and resources into their work. They live and breathe their mission, which even the best people in the secular world don’t necessarily do,” says Silverman.

The Spiritual Gap

Religious differences represent another hurdle. While Chabad adheres strictly to Jewish law, the Federation’s modus operandi is pluralism. Events that serve non-kosher food, or those that are held on Shabbat will exclude Chabad and an important segment of the Jewish community, but where Federations strive for inclusion and healthy cooperation, its events are kosher and respectful of halachah.

At times, Chabad may participate in a broader communal event with its own booth, but won’t take ownership of the program. “We constantly try to hone in on elements that we both see eye to eye on and put in the extra effort to make it work,” says Bluming. That partnership is not a workaround but directly related to Chabad’s core mission, he insists. “It is imperative for us to partner with Jews who have vantage points that may be dissimilar and see how we can widen the tent of Chabad to include them as well.”

Markovich says that he sees that core mission as the secret to Chabad’s success. “When it comes to Purim or Chanukah, or the educational curriculum of the preschool, that’s Chabad’s lane. The Federation cannot put on a Purim festival like Chabad can.” He also notes that, in turn, “Chabad cannot provide the social service resources that is in the Federation’s lane. When it comes to Jewish life, Chabad has an authenticity at its very essence that shines through, making them excel at what they do.”

Even their dress makes Chabad emissaries stand out from the crowd. “When it comes to Rabbi Shemtov, there is no hiding the fact that he’s a Jew. I don’t have a hat, or beard or wear a kippah, and I can move in and out of different circles more easily. For the rabbi, there is a level where he can never turn it off. That’s a powerful symbol to have in our community.”

A New Path Forward

Shemtov believes that Chabad and the Federation’s unique relationship in Toledo can serve as a model of partnering for the benefit of the greater community. Toledo’s Jewish community now enjoys a richer array of programming that Chabad provides in a way that it could not have done without the Federation’s participation. For smaller communities in particular, says Silverman, this may be a route to the future, where the Federation outsources Jewish programs and services through Chabad, or partners directly with them.

“The institution of the Federation has been in this community for 109 years,” says Markovich. “We know that we aren’t going anywhere and we know that Chabad isn’t going anywhere. We are both here for the long haul for the betterment of Jewish community, making us authentically good partners.”

*****

A Rare Exception: The Jewish Federation’s one-time endorsement by the Lubavitcher Rebbe

In a letter dated 1981, the Lubavitcher Rebbe wrote to Rabbi Isaac Trainin, then-director of religious affairs for the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, that he once consented to a press release “in which I endorsed the UJA Federation Campaign some years ago,” despite an established a policy of making “no public endorsements of any cause, however worthy,” other than those connected to Lubavitch.

The one-time endorsement, wrote the Rebbe, was an exception intended to show support for the UJA’s financial investment in Jewish education, both for yeshivas and day schools, as well as programs that “stem the tide of alienation, intermarriage and assimilation.” In his letter, the Rebbe noted that he was not satisfied with the level of UJA spending on Jewish education in the years since, but encouraged people to contribute to the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies campaign “to counteract the growing forces of assimilation, cults, intermarriage, etc. that are seriously eroding the very foundations of American and world Jewry.”

Decades later, at least in some cities, the Federation is beginning to make good on the Rebbe’s call. Markovich says that the results of the widely touted 2013 Pew report, A Portrait of Jewish Americans, inspired the Toledo Federation to establish a Jewish camp scholarship to connect Jewish youth with their identity. In New York, the UJA Federation distributes $1 million in scholarships to New York area families for Jewish day school tuition.

Sarah

Fascinating article!