Torah study isn’t just for school, or only in the shul. It isn’t limited to a particular age or stage in life, nor to a particular learned class or profession. But not everyone is cut out to be an academic; is every Jew supposed to be a Torah scholar?

A Scholastic Community

In his Hasidic Williamsburg, a 1995 survey of that stronghold of ultra-Orthodoxy, sociologist George Kranzler offers a brief snapshot of the state of adult education in the neighborhood. The author, who is perhaps better known as Jewish children’s book author Gershon Kranzler, writes of several large classes held in the study hall of the central Satmar synagogue. One of them –

[H]as over 500 regular participants every morning, and hundreds of others attend the evening class… throughout the neighborhood, such study classes are meeting regularly… and regularly draw large crowds. One such class is taught by an outstanding Talmudic scholar. A second huge class is taught by a specialist in… the weekly portion of the Torah. A third such popular attraction is the class on various topics of the classic and contemporary literature of Hasidism.

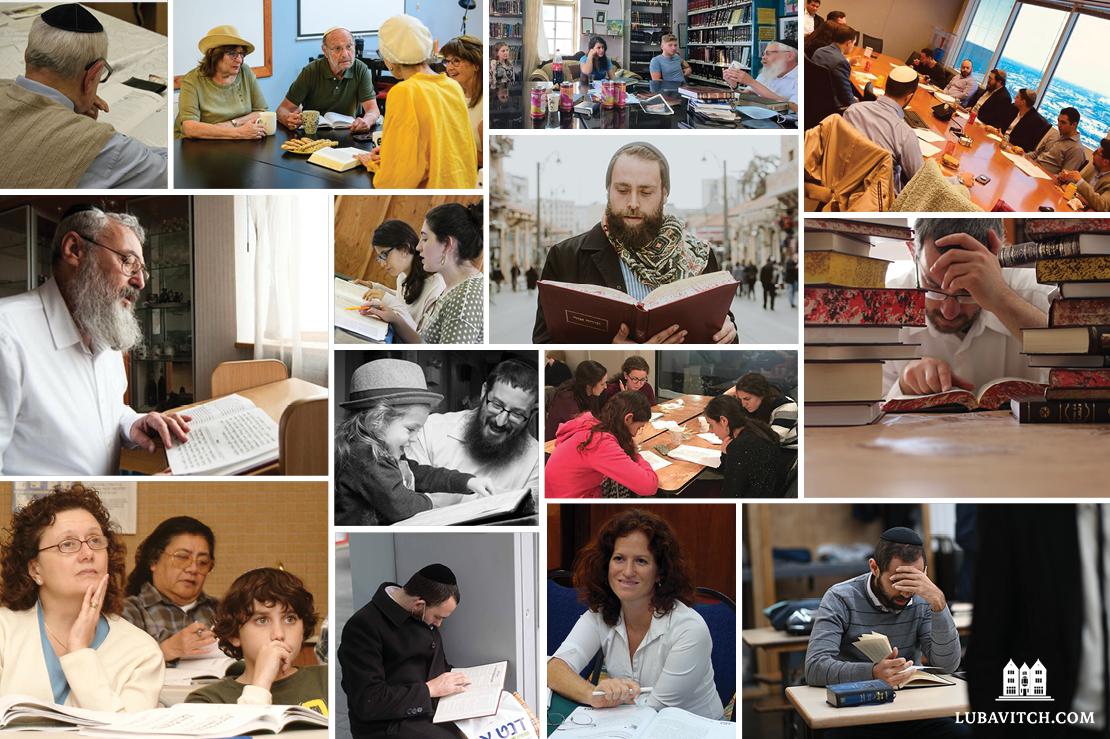

These classes, Kranzler tells us, are not attended by elderly pensioners or young yeshivah students, but “by the young and middle-aged men who have [already] graduated… and are determined to maintain their high level of knowledge.” He goes on to discuss the Daf Yomi study cycle – a seven and half year program for studying all 2,711 folios of Babylonian Talmud – as a striking illustration of the breadth and depth of the Jewish attachment to Torah study. In 1990, Kranzler writes, the largest event celebrating the study program’s conclusion filled Madison Square Garden to capacity. The most recent such event brought over 90,000 people to the MetLife stadium in New Jersey, not to mention the myriad smaller celebrations held around the world, through shuls, womens’ groups, and educational organizations.

And just who are these people packing the bleachers, those diehard Talmudists, those cheering, raucous fans of abstruse Aramaic legalese? Some are rabbis and full time scholars, sure, but there are also thousands and thousands of office workers, business owners, accountants, and shopkeepers showing up to those daily Daf Yomi lectures.

As a work of sociology, Kranzler’s book helps to make an often misunderstood community more comprehensible to the outside world. While nothing he describes would be especially surprising to the religious reader, the tradition of community-wide Torah scholarship must be a little baffling from the outside. In fact, one wonders whether the outsider has any frame of reference at all for appreciating just how remarkable this community-wide ardor for academia is. Put it this way: the closest secular equivalent of an early bird Daf Yomi class would be meeting a few buddies each day at sunrise to study Plato’s Dialogues in the original Greek.

Not a whole lot of people regularly read Plato. In the course of a year, only around half of working-age Americans will read a book for pleasure. The market for Ancient Greek non-fiction is a good deal smaller than that.

But in Judaism, this kind of ardor for ancient and arcane texts is de rigueur. Scenes similar to the ones Kranzler describes can be found in practically any mid-sized Orthodox community. Daf Yomi mania has even caught on among the otherwise unobservant. There are books, lectures, study groups, podcasts, weekly publications — even TikTok videos — all devoted to studying subjects without any obvious practical application –– from rarefied discussions of Chasidic metaphysics to nitty gritty Talmudic textual analysis.

And the Daf Yomi is just one study cycle among many. There are thousands more people learning Maimonides every day, and yet others studying Mishnah, or Scriptures, or the Tanya, or Jewish law, and on and on. Most remarkable of all is that it’s not just intellectuals with some professional interest in these subjects doing the studying. They are regular folk, with other jobs, lives, and families.

At the most basic level, the reason for all this is that there is a religious obligation to be continually occupied in the Torah. But this itself is surprising: how can we say that this imperative applies equally to a truck driver as much as it does a Talmudist?

Torah study is not just another one of Judaism’s many religious rituals. An act like giving a dollar to charity or eating matzah is objectively the same no matter who does it and no matter how fervently. As a definite physical action, a mitzvah is considered fulfilled regardless of one’s emotional state or moral character. Torah study, as a matter of the mind, is far more subjective. Since no two minds are alike, and since we process and understand in different ways, the practice of Torah study is different for every Jew.

In other words, the ability to parse a page of the Talmud depends on having a certain predisposition or level of ability that not everyone shares. We recognize that there are different kinds of smarts: book, street, and otherwise. We understand that there are ways to exercise the intellect outside the classroom, be it in birdwatching, or baseball stats, or budgeting household expenses. Troubleshooting a car that won’t start can be a deeply satisfying and thoughtful process for one person, while another will come alive to the scientific precision of pastry making.

By the same token, it should be obvious that not everyone is cut out for spending hours each day hunched over ancient texts written in a foreign language. It takes a certain kind of scholastic bent to enjoy learning about the five different kinds of restitution in Jewish tort law, or about the differences between the various meal offerings in the Temple. Maybe you can teach these things to kids in a classroom setting –– much as our school students can be made to sit through French class or basic algebra –– but can we really demand, much less expect, that they keep on learning as adults, after graduation?

College for All?

Maybe you’ve heard the joke.

When is a Jewish fetus considered viable? Once it has graduated law school.

A little off-color, but it captures well just how firmly a particular, ivy-framed view of education can set in. Without the imprimatur of a college degree, life –– or at least the comfortably bourgeois, middle class version of it –– is scarcely imaginable. It is a vision that gets pushed by parents, high school guidance counselors, and politicians alike. According to one survey, more than ninety percent of high school students report being advised to go to college.

The duty to know the entire Torah, and to spend hours each day immersed in fruitful study, is a different story. At first blush, it seems at least as elitist as any Great Books program.

But, as a recent essay in the Chronicle of Higher Education pointed out, it wasn’t that long ago that taking a non-academic education track was a perfectly respectable option in the U.S. and it still is in parts of Europe. The American shift away from vocational schools began under the Reagan presidency, and carried on under subsequent administrations. Now, at last, it seems to be reversing. Although some politicians continue to advocate for universal college access, the mantra of “college for all” isn’t heard as loudly these days. Gallup found that between the years 2013 and 2019, support for the proposition that a college education was “very important” had plummeted nearly twenty points.

It’s not hard to guess why. Skyrocketing student debt has made the four-year college a more dubious investment than it once seemed. The damage wrought by deindustrialization, and the replacement of stable factory jobs with soulless service sector and gig work (or, in some regions, no work at all) has brought about a newfound appreciation for satisfying jobs and apprenticeships that can attract recruits fresh out of high school. Crippling labor shortages of hotel housekeepers, welders, truck drivers, and so many others has done the same. The ways in which education has come to define the country’s political and class divisions has attracted criticism from another direction. Given the particular set of values and ideologies that hold sway on college campuses, some commentators have become concerned about the effects of having so many bright young people molded in this relatively narrow milieu – and then having graduates go on to form their country’s ruling class.

On a deeper level, this debate is tied to the question of what purpose higher education serves. Leaving aside their social functions, colleges are first and foremost places of learning. But what exactly are students learning there? Are they just receiving knowledge that prepares them for a career –– that is to say instrumental knowledge –– or something more than that?

The salary bump that comes with a college degree is well-established, although it should be noted that economists argue whether this is a function of learning or of credentialing. Outside of professions like medicine or engineering, employers care less for what the graduate has learned than for the degree. In any case, the real training only starts on the job.

But educational theorists like E.D. Hirsch have emphasized the role of education in transmitting important knowledge, through titles like What Your First Grader Needs to Know and his “Core Knowledge Series.” Mortimer Adler and Robert Hutchins of the University of Chicago developed a “Great Books” program for teaching students the West’s most vital ideas. Whether because they tackle perennial questions of life and human nature, because they stimulate personal growth, or simply because they transmit knowledge itself, teaching “the best that has been thought and said in the world” is surely a worthwhile cause, even if it doesn’t make any money.

Regardless, it’s understood that college isn’t for all. For some people, electrical work is a lot more fulfilling and lucrative than middle management will ever be – and it’s a good thing, too, since we need electricians. That not everyone is suited to hardcore academia is even more self-evident. Great Books schools, like Maryland’s acclaimed St. John’s College, are small for a reason. A recent book by Columbia University’s Roosevelt Montás has argued for making education in the classics less elitist; but the fact is that the number of people who have read through the Western canon will always be a very small club. You wouldn’t have much trouble fitting them on a half court, let alone Madison Square Garden. It seems obvious, in other words, that we can’t expect everyone to devote years of their lives to bookish contemplation. Plato certainly didn’t think everyone was cut out to be a philosopher.

So why does it seem that the opposite applies with respect to Torah study? Is every Jew cut out to be a Torah scholar?

Laying Down the Law

In 1794, a small treatise published anonymously in Shklov, a White Russian bastion of scholarship and anti-Chasidic fervor, caused a minor stir. Torah study was in fact the subject of the book, which was really more of a pamphlet. The Laws of Torah Study provided a bold but elegant restatement of the halachic obligations surrounding the study and teaching of Torah. Instead of basing his work on existing Codes of Law, the author essentially started from scratch. Working from the first Scriptural sources down to latter-day rabbinic authorities, the author clarified old questions, resolved apparent contradictions, and brought some order to the subject in the course of four concise chapters, and a few deeply learned and recondite footnotes.

According to one account, within three months, the entire print run of four thousand copies was sold out. The population of Shklov at the time wasn’t much more than three thousand, of which eighty percent was Jewish, but the city’s Hebrew printing presses served all of Eastern Europe. When the pamphlet reached the study halls of Lithuania, the great Gaon of Vilna himself was said to have praised it, and lauded those footnotes as the work of a genius.

As it turned out, the commotion caused by the publication was due not to its content but rather to its author. Behind Laws of Torah Study was none other than Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the Alter Rebbe, who was fast emerging as a bête noire of the Lithuanian opponents of Chasidism, and would soon be famous as the author of one of its seminal works, Tanya. When his true identity was revealed, those opponents claimed that the whole thing had been a ruse to infiltrate the Lithuanian Torah world.

But beyond this dramatic little episode, Laws of Torah Study was notable because of its genuine halachic innovations. The late Rabbi Mordechai Ashkenazy, author of a magisterial six-volume commentary on Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s slim treatise, notes with some irony that Torah study as a subject in and of itself had been largely unexplored until then, such that “more was hidden than revealed.”

As the Alter Rebbe saw it, the command to study Torah contains several constituent obligations. The same distinction we previously saw between the practical and theoretical, or between instrumental and non-instrumental reasons for higher education, can also be applied to Torah. Being religiously observant requires, simply put, knowing what to do. But that isn’t enough. Beyond a familiarity with practical and pertinent halacha, we also have a duty to study Torah without thought for utility. Here, Rabbi Schneur Zalman makes a novel distinction between an obligation to know and another to study the Torah.

Now, when he speaks of the obligation to know Torah, Rabbi Schneur Zalman doesn’t just mean some of it. As he writes in Laws of Torah Study, it means “all of the Written Torah, as well as the Oral Torah in its entirety,” and “all of the mishnayot, the braytot, and the sayings of the sages of the Talmud expounding on the 613 commandments, with all of their conditions, and particulars, and all of the particulars of Rabbinic law. In our times, this also includes the legal decisions of… the authorities like the Tur, the Shulchan Aruch, and its glosses . . . [it also includes learning] the reasons for those laws . . . [in] works like the Rosh and Beis Yosef.”

Many of our greatest personalities in the Talmud were, far from being professional scholars, employed in the trades or in blue collar work: Rabbi Yochanan the cobbler, Abba Oshiya the launderer. That humble exterior made the vast erudition and learning that lay within all the more extraordinary.

In case it’s not clear, that is an astounding amount of information, even if it is ultimately finite, as Rabbi Schneur Zalman hastens to add. At one point, he suggests learning it all would take some ten years of full time study. For most of us, it would doubtless take longer. Even more astonishing, the obligation is not only to read through all of those texts and to understand them, but to actually remember them, or at least maintain a regimen of review to ensure one retains them. In Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s radical view — and bear in mind that most authorities don’t go quite this far — there is a biblical prohibition against forgetting one’s knowledge of Torah.

Separate from this is the obligation to study Torah. Here the subject matter isn’t just the practical laws, or commandments that do not presently apply, but everything. The point isn’t trying to conquer a fixed body of knowledge, but the action of studying itself — of being constantly engaged in the Torah. When Joshua is told, “This book of the Torah shall not leave your mouth; you shall meditate therein day and night,” this is what it means. It is a duty as limitless as the Torah itself, and, in its highest form, it is motivated by no utilitarian reason at all. More precisely, it is learning for the love of learning, for the Torah’s own sake, and to be connected to the divine source from which it emanates.

The Blue Collar Scholar

So just who is supposed to do all this learning?

First and foremost, it is clear that the most basic obligation to learn Torah – the instrumental study of what to do or not to do — is meant for everyone. Just as the Torah has laws that apply to every Jew, the obligation to become familiar with those laws applies equally.

The duty to know the entire Torah, and to spend hours each day immersed in fruitful study, is a different story. At first blush, it seems at least as elitist as any Great Books program. Throughout his Laws of Torah Study, Rabbi Schneur Zalman makes reference to people who are, either by nature or circumstances, unable to abide by the standards of Torah study he sets forth. A father might “have to be occupied with work in order to provide for his wife and children, and be unable to spend the entire day occupied in Torah.” Someone else might be “very forgetful, by nature and by birth.” Another is, simply, a “boor”. These terms are not meant as pejoratives, but as factual descriptions. Given how high the bar is set, it is entirely unsurprising that most people will struggle to clear it.

The Sages denounced those who would seek Torah knowledge for the sake of social advancement. Yet it’s easy to see how this knowledge – given how central it is to Judaism and how hard it is to meet the demands of Torah study – might create the conditions for a hierarchy, de facto if not de jure, of the knowers and the know-nots.

Indeed, at times in Jewish history, a deep divide emerged between the simple folk and the scholarly elite. It has been argued that the central complaint leveled against Chasidim was that they downgraded the importance of Torah study, and by extension the status of those who studied it. Of course, the notion that Rabbi Schneur Zalman devalued the obligation to study Torah in any way is put to the lie by simply reading his Laws of Torah Study (see also chapter five of Tanya). If anything, one might have thought that the exacting standards laid out there would only cement those hierarchical divisions, by elevating the scholars and leaving the rest behind.

To the contrary, while the Alter Rebbe elevates the demands and the significance of Torah study, he also expands the franchise. Time and again, the Alter Rebbe endeavors to explain how the obligation to know and to learn, or the reward for doing so, extends to every individual in some way or another. It is both universal –– and elastic. In discussing those who are not fully equipped to fully meet his high standards, his point is never to exclude or excuse, but to include them in this enterprise.

For someone who struggles to understand legal reasoning, the Alter Rebbe recommends focusing on just learning the laws. For someone who forgets, he recommends a detailed course of learning and regular review, so that he only learns as much as he can retain. “Every person is obligated to remember the words of the Torah,” he writes, “in accordance with his abilities and his powers of recall, whether that means a lot or a little Torah.” Thus the Torah both individuates and unifies. The Mishnah famously extols Torah study as being “commensurate to them all,” meaning all the other commandments. In a play on the Hebrew, Rabbi Ashknazy writes that, with his little treatise, Rabbi Schneur Zalman “explained the obligation to study Torah, and a study program, for each and every person, without exception.” Truly, the Torah is for all.

While the Alter Rebbe elevates the demands and the significance of Torah study, he also expands the franchise.

The Alter Rebbe was not the first to articulate the remarkable flexibility of the obligation to study Torah. The Talmud itself explains how even the busiest person can fulfill the divine command to learn day and night.

Rabbi Ami says… even if a person learns only one chapter in the morning and one chapter in the evening, he has thereby fulfilled [the instruction given to Joshua:] “This book of the Torah shall not depart from your mouth, and you shall contemplate in it day and night…”

Rabbi Yoḥanan says in the name of Rabbi Shimon ben Yoḥai: Even if a person recited only the recitation of Shema in the morning and in the evening, he has fulfilled it.

The saint disguised as a simpleton is a familiar figure in Talmudic and Chasidic lore. Actually, many of our greatest personalities in the Talmud were, far from being professional scholars, employed in the trades or in blue collar work: Rabbi Yochanan the cobbler, Abba Oshiya the launderer. That humble exterior made the vast erudition and learning that lay within all the more extraordinary. There is something equally inspiring about the plumber, or the harried businessperson, or the Uber driver, who are exactly as they appear to be, but still manage to catch up with Maimonides every day, or to tune in to a class on stories of the Talmud. By carving out those few minutes — that “one chapter in the morning, and one chapter in the evening” — they fill their lives with the Torah.

Famously, the Torah is compared to water, for the way it represents a source of life, descended from heaven. And, like water, it flows downward, into whatever containers we put out for it, and fills each one, according to its shape and size. In essence an otherworldly wisdom, the Torah comes down to meet and engage with the realities of our world, the particulars of our nature, the circumstances of our lives. For some, it is a guide to practical living. For some, it is the key to our cultural and religious heritage, a way of connecting with our rich traditions, and an integral part of our Jewish identity. For some, it is a way of life, a full time occupation in which the work is the reward. For all, it is a gift from G-d, and a way of connecting with Him. To each of us, it has something to offer, and we all have something to contribute to it.

This sentiment is expressed in the famous verse, which is the first line of Torah a father teaches his son: The Torah was given to us by Moses; it is the inheritance of the Congregation of Jacob. Who is Torah study for? All of us. The full time scholar, the morning commuter, the working mother. It’s for morning and night, on the train to work or the middle of the day, in rain, snow, or shine. Finding out how to fit Torah study into our lives, working out time and a method of study, and discovering a part of Torah that resonates can be hard work. For some, it will be a long journey, starting with the letter Aleph, and then on from there. But the thing about an inheritance is you don’t have to earn it. As a Jew, it is something to which you are entitled by birth. This is the essential point: no matter who you are, your ability, or stage in life, the Torah is already yours.

This article appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of the Lubavitch International magazine. To download the full magazine and to gain access to previous issues please click here.

Be the first to write a comment.