Elisha Wiesel speaks with Lubavitch International about his famous father and raising his children to love Yiddishkeit

Your father, Elie Wiesel, put the tragedy of his personal experience in the Holocaust to work, raising awareness about the danger of antisemitism and the evil of hatred. You yourself have begun to speak out against antisemitism, sometimes — as you did at the UN this past February — with indignation, even anger. Is that something you’d say came from your father?

My father was not an angry person, so I won’t blame him for this. But I think there’s a time and a place to get appropriately angry. Today, being a victim seems to be the only way to get the microphone. We shake our heads and sit there stunned, shocked—for example—by the stupidity of the argument against Israel about “disproportionate killing.” This rhetoric is absolutely antisemitic, absolutely hateful, because the only way to get “proportionality” is to turn off the Iron Dome for an hour so that more Jews die. So we need to raise our voices. We need to respond. Sometimes, you have to get angry with these people, because it’s the only way that they realize they have crossed a line—from pontificating to calling for absolutely murderous results.

The world knows Elie Wiesel as the most famous Holocaust survivor, a prolific author, activist, and Nobel Peace Prize winner. Who was Elie Wiesel to you, his only child?

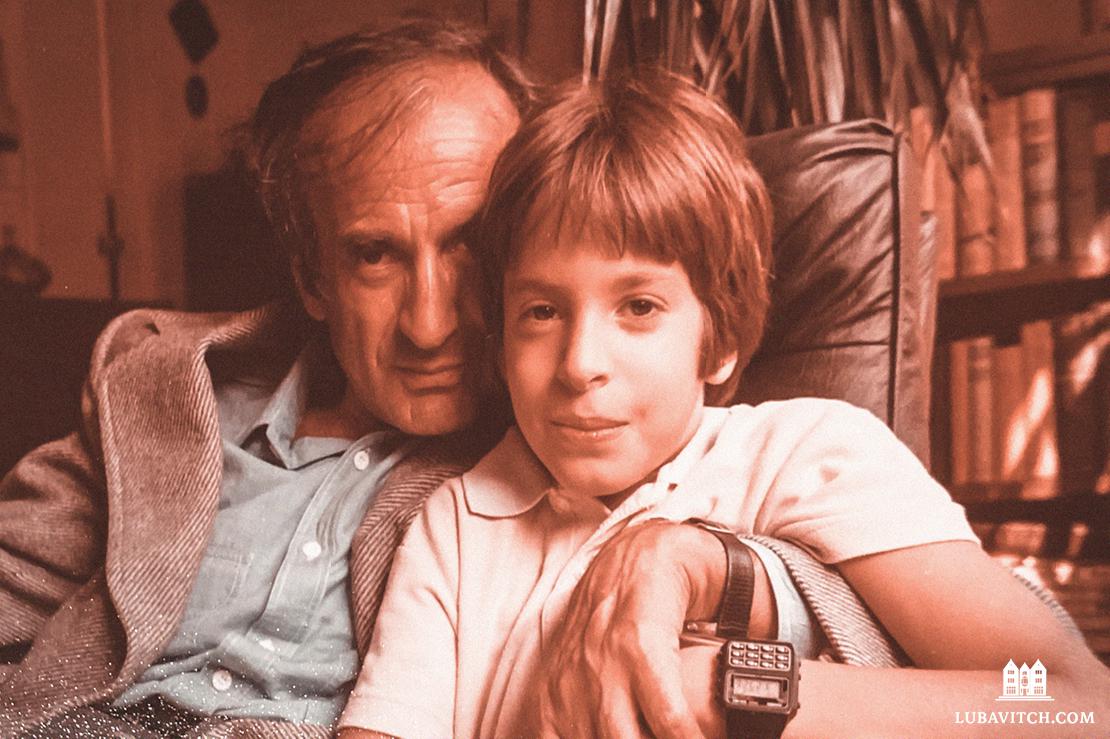

When I was young, I thought my father was a weak person. A lot of the other kids had parents who were throwing a baseball with them, teaching them how to catch a football, taking them skiing. That was not my father.

At age eight or nine, I’d hear a friend say his father had served in the IDF and was now flying planes for El Al. Another would say his father was a pharmacist, saving people with his medicines. I would say, “I think something really bad happened to my father, and he talks about it.”

But my impression of my father changed a lot over the years. In my twenties, I began to appreciate the person who existed before the war. He was a bright, engaged, curious student, full of affection. I began to appreciate the incredible childhood that he had and I could see the young person that he’d been. I no longer saw him as just a snapshot.

You once said that you struggled as a child: it was difficult being in your father’s shadow and trying to carve out your own identity. What were you looking for?

I felt that there was this path that had been constructed for me, and an expectation that I would be a mini Elie. I went to a Modern Orthodox yeshivah where my father was very well known. So, of course, I was supposed to be the best-behaved student in class. I mean, your father is Elie Wiesel, so how could you possibly be goofing off and not paying attention? I felt very boxed in by all of the expectations of who I was supposed to be. I was desperate to break out.

What did that look like?

As an adolescent, I went through a very strong inflection point. I began to question everything. I felt Yiddishkeit was useless to me, and I found myself completely on the other side.

How did your father relate to your adolescent frustrations?

He didn’t always know how to connect with me. My parents were first-generation immigrants from European families. They didn’t get a guidebook on how to be an American parent in the twentieth century, and I think they struggled with it. My father was a very patient man, and he continued to love me no matter what horrible things I said or did. Ultimately, I think that that served him well as a parenting strategy. It’s one that I try to remember. But I’m sure it was very hard for him.

I think my father felt that he had placed a big burden on me by bringing me into this world. At a time when it was hard for anyone to keep faith and fight the forces of assimilation, it was a difficult thing to be the son—the only son—of a famous Holocaust survivor whose family had been almost decimated. And he felt bad for me that all that weight was on my shoulders. He tried to lessen the burden. He tried to protect me and let me live my own life.

What was the turning point in your relationship with your father?

In 1995, I joined my father on a trip to Sighet, his childhood hometown. That was a turning point. We also went to Auschwitz on that trip, but that’s where the Jewish community went to die. Sighet is where the Jewish community lived. In Sighet, my father could describe what his day looked like, how he would run home from cheder, or from choir practice, stopping at his grandmother’s window–on Fridays she had a fresh challah to give him as she asked him what he learned that day. This was powerful for me.

This is where my father grew up, and it’s charged with all fourteen or fifteen years of his memories before Auschwitz. Being there allowed me to see him as someone who had this incredible strength to persevere, with life, with family, with Yiddishkeit, and to engage with the world after the Shoah.

Where do you think that resilience came from?

It came from the way he was raised. My father was not raised in a vacuum. I could feel my grandparents’ fingerprints in all this.

My father loved Judaism, loved the world. He had an incredible thirst for knowledge. You don’t get that in a vacuum. He was raised in a loving home. He had a strong sense of identity. And when you have that, you have the self-confidence that can take you forward in life.

This is something that I only appreciated when I had kids of my own and started thinking about what shapes character and what shapes destiny.

Were there other turning points for you?

Growing up, I didn’t get to experience a big family or joy in Judaism, and that was really missing for me. But my father gave me a gift when he passed. He wanted me to say Kaddish for him, and when I started to visit shuls to do so, I saw joy. I saw joy in the davening, joy in everything—from Birkat HaMazon, to the Torah class, to the kids running around.

The joy of Yiddishkeit seems to be an important theme in your family life.

We only get this narrow window to give our children the values and experiences we want them to remember. I want my son to have experiences he’s going to remember ten years from now, when he has to make his own decisions about life. I don’t feel I’m going to get my kids to have a lifelong interest in Judaism by lecturing or giving them rational arguments.

What he will remember is that he and a friend would sit in shul and have a good time together, and occasionally they’d get up and dance with us and run around. He’ll remember the experience of the lively singing, and he’ll know the songs and be able to sing along. He’ll remember that great feeling at the Shabbos Kiddush in shul, where you’re schmoozing and the food is great, and people are happy to see each other. These are things he’s going to remember—in his heart, not in his head. So I’m much more focused on that.

My son is almost sixteen. And I’m respectful of his time and his choices. He knows that I expect him to wear tefillin with me every day. He doesn’t go to a Jewish school, so we daven together every morning. We go to shul together when we can, and we experience the liveliness, the spirit of Yiddishkeit.

Your father was a serious student of Gemara. He loved learning Talmud, he said. You also are studying Talmud. What has that been like?

I’m on this seven-year adventure, making my way through all of Shas, seeing every corner of the Talmud. I study with a chevruta. I could spend the rest of my life studying, because how can you possibly master this conversation that’s been occurring for 2,000 years? We’re flying 1,000 miles an hour at 30,000 feet, so I know that I’m not getting it in depth. But occasionally there’s something that I want to double-click on and go deeper. I’m keeping a journal of the things that I find the most memorable so that when I do it the second time around, I can go even deeper. It has been an incredible experience.

It’s also taught me to appreciate the depth in which my father was swimming, and what he was inspired by. I’ll be sitting in shul and reading a certain Haftorah, and I know what my father would have been thinking about.

In a 2012 interview in these pages, your father spoke about his personal relationship with the Lubavitcher Rebbe. He said the Rebbe urged him to marry and have a family.

I have only one side of their correspondence—the letters the Rebbe wrote to my father. No matter what they would be talking about, the Rebbe would end by saying, “By the way, are you married yet?”

He was constantly reminding my father that this was the most important thing he could do to really defeat Hitler. To really show that he stood for all the things he said he stood for: “You need to get married, you need to have kids, and they should grow up to be Chasidic, G-d-fearing kids. And if they’re not Lubavitch, that’ll still be good.” He did it with a sense of humor.

Did your father live to see the way you have evolved?

He didn’t live to see my son’s bar mitzvah, which I’m very sad about. But he lived to see my kids have Jewish literacy. He taught my son alef-bet on his knee. And he saw that we were beginning to make Shabbos a joyful time, that I could raise a Jewish family with joy very much at the center of the experience.

This article appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of the Lubavitch International magazine. To download the full magazine and to gain access to previous issues please click here.

Abby Gilman

Thank you for this beautiful enlightening story. Eli Wiesel’s memory is truly a blessing.