In a eulogy at the quiet funeral—limited by pandemic regulations to thirty people—of Rabbi Jonathan (Yaakov Tzvi) Sacks, one of his colleagues sang the stirring Chabad melody, Tzamah Lecha Nafshi, “My soul thirsts for you in a desolate and weary land without water.” The Psalmist’s words (63:2-3), Rabbi Sacks had once said, were what he wished for as his epitaph.

Rabbi Sacks served as Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth from 1991 until his retirement in 2013, when he was feted by the Prince of Wales at a dinner in his honor. The prince spoke at length about the extraordinary contribution Rabbi Sacks had made to him as a friend, an adviser, and “a light unto this [British] nation.”

His light went out on Shabbat, November 7, in the throes of the political hostilities and strife that made his moral voice on the conflicts of our times more urgent than ever. He wrote numerous books spanning themes of ethics, morality, and the role of faith in the modern age. Among them: To Heal a Fractured World, The Politics of Hope, The Dignity of Difference, and, most recently, Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times.

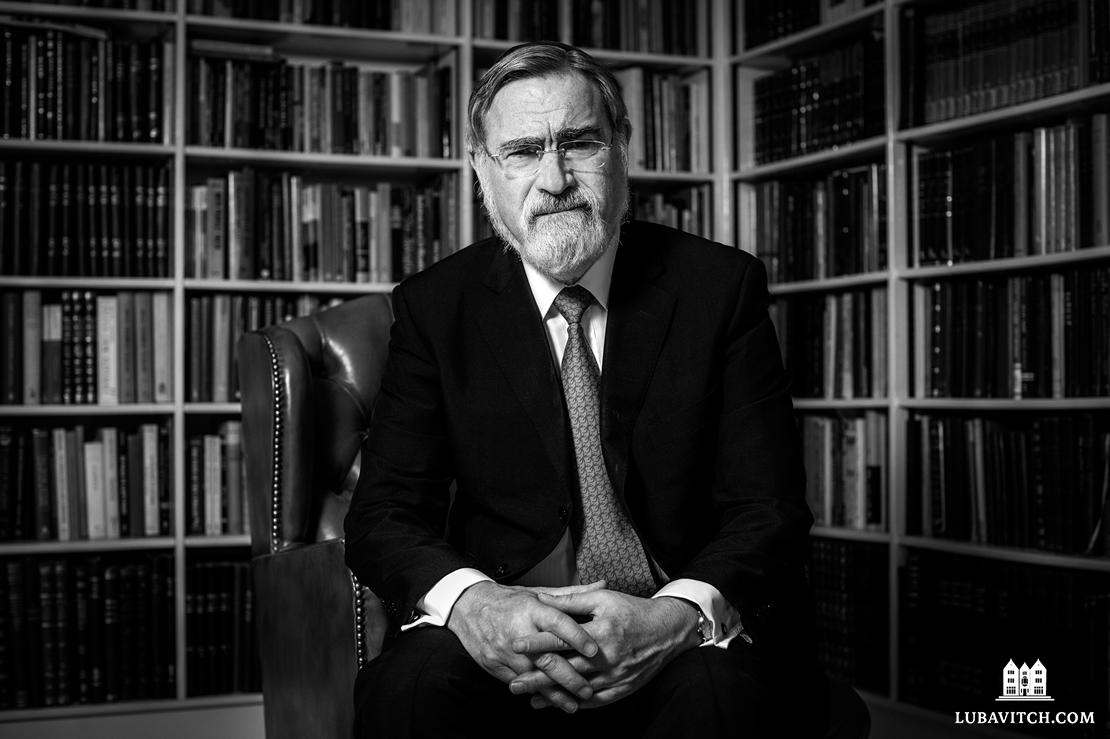

The outpouring of tributes to this “gentle giant,” as one of his students aptly put it, offer glimpses of his captivating presence and the magnitude of his influence. Rabbi Sacks held court with kings, cardinals and philosophers, distilling the wisdom of Judaism with rare intellectual and oratorical eloquence. He spoke about the “Three loves” commanded in the Torah: “Love G-d . . . Love your neighbor . . . Love the stranger . . . .” This became the theme underpinning much of his work within the broad Jewish community and on the world stage where he fostered friendships and respect across different faiths by dignifying differences.

I had the privilege and great pleasure of interviewing Rabbi Sacks shortly after he retired from his post as chief rabbi. I asked him what were his greatest moments of joy during his twenty-two years in the role.

If I thought he would talk about being knighted by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth in 2005, I was mistaken. Nor did he mention that he had been made a Life Peer in the House of Lords, the riveting speech he gave at the Vatican, or the numerous honorary degrees and prizes conferred upon him.

Instead, Rabbi Sacks recalled a Torah-dedication ceremony. “In England, Jews tended to keep a very low profile, so the first time we did a Hachnasat Sefer Torah, and we took the Torah scroll through the streets, it was a big moment for us. We’d never done this. By the time I finished, the local police chief came and danced under the chuppah with the Torah; the policemen were dancing along with us.

“We took that joy out into the public domain, into the streets, the way the Rebbe did with the menorahs on Chanukah . . . And the thing we discovered is that when you do this, you bring joy to the world.”

Rabbi Sacks often expressed his humble gratitude for the Lubavitcher Rebbe who, he said, had shaped his attitude to leadership and moral responsibility. “The Rebbe took an unknown student from thousands of miles away, and lit a light in his soul that has burned from that day to this,” he said at a public event.

As a university student, he sought the Rebbe’s advice about a career path, and presented three possibilities. The Rebbe rejected all three and proposed a fourth, advising him to become a congregational rabbi and train other rabbis. Although at the time, he hadn’t imagined himself in a leadership role, he followed the Rebbe’s advice. “The Rebbe was my satellite navigation system, showing me where to go and how.”

Later, when the invitation to serve as chief rabbi came up, he again consulted with the Rebbe who advised him to accept the position. In his exalted role, Rabbi Sacks, the most sought after rabbi, teacher and public intellectual of recent decades, looked to the Rebbe. With his singular insight, he analyzed the Rebbe’s activism, articulating it in his inimitable poetic phrasing: “If the Nazis hunted down every Jew in hate, the Rebbe would search out every Jew in love.”

As chief rabbi, he translated that love into a calling to be more Jewish. “Non-Jews respect Jews who respect Judaism. And non-Jews are embarrassed by Jews who are embarrassed by Judaism,” he said famously. Toward that goal, he led a brilliant Jewish continuity campaign to promote Jewish day schools for Jewish children. How well our children will care about being Jewish, he told me, depends on “the number of years spent at Jewish day schools, or the number of years spent exposed to serious Jewish education.” The campaign was so successful that by 2013, the number of Anglo-Jewish children enrolled in Jewish day schools had tripled.

From his seat in the upper chamber of the British Parliament, he spoke out against antisemitism with words that have since reverberated widely: “If antisemitism is the paradigm case of dislike of the unlike, of hatred of difference, it follows that a country that has no room for Jews has no room for humanity.” But he had profound faith in a positive future. He seemed upset when, in our interview I suggested that perhaps the age-old hatred of the Jew is incurable. He insisted emphatically, and now, prophetically, that “there can be a friendship between Jews and Muslims . . . none of us should see antisemitism written into the fabric of the universe; it isn’t. It is not inexorable and we have to cure it.”

Rabbi Sacks embraced science as a necessary complement to faith. “Science is the conquest of ignorance. Religion is the redemption of solitude,” he wrote in his book, The Great Partnership. He spoke often about the immense difference that the presence of G-d makes to our lives. How, I asked him, can a rabbi make G-d personal to others?

“G-d has to be personal to the rabbi before he can make G-d personal to anyone else. I always talk about my late parents of blessed memory. . . . They never had an education, but we saw from our parents how they loved Yiddishkeit; it made them walk taller.

“I don’t know if my father could even understand all the davening, but he knew who he was. And I had the biggest privilege in my life seeing him walk on crutches up the steps of the S. John’s Wood Shul to open the Ark at my induction as chief rabbi. And I thought: ‘Dad . . . I want you to know that I learned emunah [faith] from you. You taught me what it is to have a personal relationship with Hakadosh Baruch Hu [G-d].’ And when you do that, you can communicate it to anyone. But first you have to feel it.”

In his noble bearing, Rabbi Sacks struck an exquisite balance: a man of the world who graced the halls of parliament, royalty, and academia with the wisdom of Torah, the love and awe of Heaven, and the courage of his Jewish values. Rabbi Sacks demonstrated that it is in the fullness of our humanity that we reflect the image of the Divine, and that it is precisely through attention to the particulars of their tradition that Jews become a light to the world.

His passing is a titanic loss. His legacy is a wellspring of solace.

Be the first to write a comment.