After a year of restricted movement around the globe, wanderlust is stronger than ever. As the most vaccinated country in the world, Israel is at long last opening her doors this summer, welcoming tourists back to the Holy Land. For those seeking a spiritually enriching trip, there is no better place to visit than the mystical city of Safed, or Tzfat, perched atop Israel’s Upper Galilee region.

The city’s awe-inspiring vistas peek out around winding cobbled street corners, and ancient stone synagogues whisper of an illustrious history of scholars and sages. Lubavitch International explores Israel’s northern gem and the formation of a modern-day Chasidic colony. A meeting point of Kabbalah, art, outreach, and education, the city of Tzfat continues to draw spiritual seekers from around the world.

Zev Padway’s breath caught in his throat as the bus twisted and turned around sharp, hairpin curves. He could still make out the misty edges of the Sea of Galilee far below him. Before him, a city of ancient stone buildings came into view.

As the 27-year-old stepped off the bus in 1993, he breathed in the fresh mountain air and sighed.

“They were right.”

Just weeks earlier, Zev had arrived in Israel on a spiritual quest. At the time, he was a Hare Krishna devotee, devoted to Hinduism. Since his late teenage years, he had dabbled in every spiritual tradition imaginable, from gypsy Rainbow Gatherings to Quaker prayer circles. Every tradition, that is, except his own. His boring Sunday School classes at the Reform temple had convinced Zev that Judaism had little to offer. After experimenting with various religious traditions throughout his twenties, he felt a calling to visit the Holy Land. He bought a one-way ticket to Israel.

“As soon as the plane landed in Ben Gurion airport, I felt two things I never felt before,” Zev shares. “One: that I was home. Two: that I don’t know anything.”

Zev backpacked to Jerusalem and settled in at a youth hostel in the Old City, where he began exploring his roots. It wasn’t long before the director of Heritage House pointed him northward, suggesting that his place was the ancient city of Tzfat.

“You are a Tzfat Jew,” Zev recalls him saying.

Zev arrived on the eve of Yom Kippur. He offloaded his bags at the Ascent hostel, and then left to wander the streets. There, he joined a busy crowd on their way to immerse in an ancient mikvah before the holiest day on the Jewish calendar. Rabbi Isaac Luria Ashkenazi, known as the Ari (or the Arizal), lived in Tzfat in the 1500s and is considered to be the father of contemporary Kabbalah. His mikvah – a natural spring used for spiritual purification – is located at the bottom of a steep mountain slope, adjacent to the Old Tzfat Cemetery, is famed for guaranteeing that whoever immerses in its icy cold water will ultimately “return.”

Always ready for a new experience, Zev proceeded to immerse himself in the waters and felt a “transformational” rekindling of his Jewish soul. Indeed, those first twenty-four hours in Tzfat, on the holy day of Yom Kippur, would alter the trajectory of Zev’s life forever.

Kabbalistic Calling

Home of the Renaissance Kabbalah masters, Tzfat has attracted spiritual seekers for centuries.

“In Jewish tradition, Israel is home to four holy cities, each one represented by one of the four elements,” says Rabbi Binyamin Alexander, 72, a Sydney transplant to Tzfat who teaches Kabbalah at Ascent, a Chabad-run educational and visitor center in the city. “Jerusalem is the City of Fire, recalling the sacrifices brought at the Holy Temple. Hebron is Earth, for the Patriarchs and Matriarchs buried there. Tiberias (Teveria) is Water, and Tzfat is the City of Air, the birthplace and home of Kabbalah, Jewish mysticism.”

Literally in the air at eight hundred meters above sea level, Tzfat was home to some of the greatest writers of Jewish mystical texts. Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, author of Judaism’s foundational Kabbalistic work, the Zohar, lived in the region and was buried on the neighboring mountain of Meron shortly after the Second Temple period.

Right: Medieval art adorns the dome of the Abuhov Synagogue

Centuries later, in the 1500s, the Arizal became the leader of an eclectic band of scholars and mystics who elucidated the difficult text of the Zohar and elaborated on its meaning and mysteries.

Other visionaries who made their home in this tiny hamlet in northern Judea include Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, who integrated differing schools of Kabbalistic interpretation into “Cordoverian Kabbalah”; Rabbi Chaim Vital, the protege of the Ari; Rabbi Moshe Alshich (see A Man of the People in the City of Mystics, page 24); Rabbi Jacob Berav, best known for his attempt to reintroduce classical rabbinical ordination; Rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz, composer of the Lecha Dodi prayer, still recited by every Jewish community around the world today to welcome Shabbat; and Rabbi Joseph Karo, author of the Shulchan Aruch, the authoritative codification of halacha, Jewish law. In the generations to come, those drawn to the city included many followers of the Chasidic movement, founded in the eighteenth century, whose teachings drew heavily upon the Ari’s Lurianic Kabbalah.

“The spirituality of these Torah giants is still tangible here,” shares Alexander. “There is a uniquely mystical atmosphere. The cobbled alleyways we walk echo with holiness.”

Alexander did not grow up in a religious home. He only began exploring Judaism in depth after struggling to answer his children’s questions about Jewish tradition. He connected with Chabad emissaries in his hometown of Sydney and began his long trek back to his roots. In 2000, Alexander remarried and moved to Tzfat, where his wife became an artist and designer at the famed Safed Candles. “The greatest thing I ever did was move here,” he says.

Today, on any given Friday night, one can walk the streets of Tzfat’s Old City and hear the melodic tunes of Shabbat prayers sung by young congregations in ancient synagogues. The melodies spill out of every narrow alley, harmonizing in sacred songs of devotion. This aura of peace and sanctity recalls those early mystics who would descend into the fields surrounding Tzfat each Friday at sunset, singing psalms and poems to welcome the Shabbat Queen.

Right: A view of the old cemetery in Tzfat

The Shtetel Reborn

Despite this appearance of idyllic continuity, the city’s transition from an ancient Kabbalistic outpost to a modern, thriving community was not a smooth one. After its golden age in the sixteenth century, the city was ravaged by changing empires, a Druze rebellion, a devastating mid-nineteenth-century earthquake, and a 1929 Arab riot that decimated the Jewish community. In 1948, after a miraculous Arab retreat in Israel’s War of Independence, Tzfat was a shell of its former self, with a frail and impoverished Jewish community left to pick up the pieces. The city languished for years, with few incoming immigrants willing to settle there.

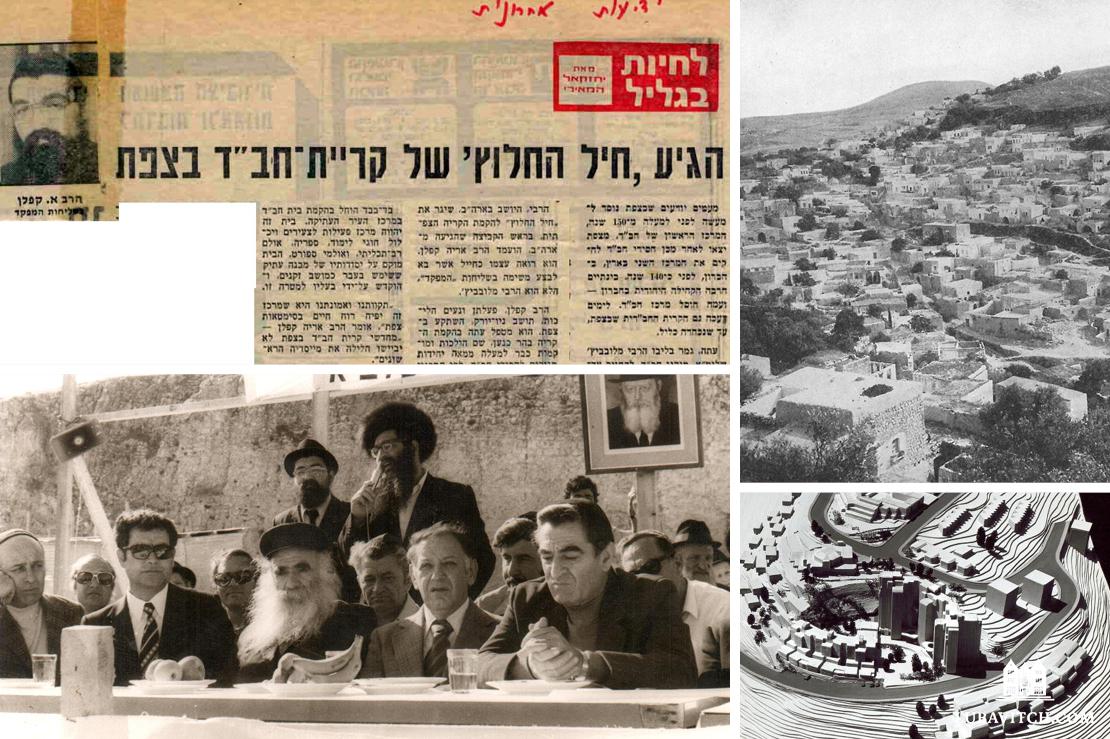

On August 3, 1970, the Lubavitcher Rebbe received a short bulletin from the city council of Tzfat regarding the historic Chabad synagogue in the Old City. The structure was about to collapse, and the council inquired if Chabad Headquarters in Brooklyn would be interested in renovating. If not, the building would be demolished.

Built in the early 1800s by followers of the third Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel, also known as the Tzemach Tzedek, the synagogue served some of the earliest Chabad immigrants to Israel. Noting its historical importance, the Rebbe halted the demolition and focused his attention on restoring not only the synagogue, but also the Chasidic community that had thrived there in previous generations.

“The Rebbe had a vision for restoring Tzfat to her former glory,” says Rabbi Chaim Kaplan, the head Chabad emissary in the city today. “From the start, this was a large-scale project for Tzfat to become a major center for Chabad in Israel. In his early correspondence, the Rebbe wrote of founding schools and yeshivahs, bringing in young families and immigrants, building a center for tourists, and expanding Chabad’s reach to build up the entire city.”

In 1973, Kaplan’s father Rabbi Aryeh Leib Kaplan, aged 25 at the time, and his wife, Sarah, were sent by the rebbe as his new emissaries to Tzfat. To help them in their restoration work, they recruited ten young Chabad families who would establish a presence in the Old City. Working with the city council, Rabbi Kaplan secured a large plot of land in a newer Tzfat neighborhood, and construction began on apartment buildings for 150 families, with plans for another 150 in the pipeline.

A project of such scale in a city that lacked the basic essentials of modern living was met with consternation. Telephones were rarely accessible, drafty stone buildings had no heating, and travel to central Israel took well over six hours. Who would want to move to Tzfat? “The situation in Tzfat was far from ideal, even in comparison to the rest of Israel, which was light-years behind the United States,” Mrs. Sarah Kaplan said in an interview with Derher magazine. Israelis thought it was like moving to the moon.” Still, the Kaplans plowed ahead.

What followed is a modern-day tale of a Chasidic shtetl reborn. In the late ‘70s, thirty American Chabad families were sent by the Lubavitcher Rebbe to join the Kaplans in Tzfat. The young English-speaking couples, driven by a sense of idealism, would eventually become some of the most influential rabbis and educators in Israel — some serving as chief rabbis of Israeli cities today.

In 1998, Rabbi Aryeh Leib Kaplan was tragically killed in a car accident while traveling to the inauguration of a Chabad center in Russia, and the mantle of Chabad leadership in Tzfat was passed to his son Chaim. “It was an unusual approach to build up a Chabad community in the north,” says Rabbi Chaim. “Most Chabad emissaries were charged with raising the Jewish consciousness of their communities. My father was charged with building a community of Chabad educators, who would then fan out and educate others country-wide and abroad.”

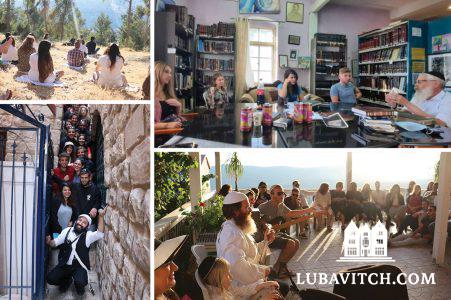

Today, Tzfat boasts seventy official Chabad emissaries, with dozens more working in educational and outreach capacities. Countless students and visitors have returned to their Jewish roots through the Chabad educational institutions that were founded there over the past fifty years. From the revived Tzemach Tzedek synagogue in the Old City, to outposts in the Artist’s Quarter, busy soup kitchens, and educational institutions running the gamut from preschool to postgraduate, Chabad is deeply embedded in Tzfat life.

“The Chabad community is the largest religious demographic in the city, at about 15 percent of the population,” says Kaplan. More than a thousand children are enrolled in thirty Chabad kindergartens and schools across the city, and over 1,300 high school and college-age students come from around the world to spend a year of learning at immersive Chasidic seminaries and yeshivahs.

Chabad’s Chasidic theology is an ideal match for the aspiring students of Kabbalah who flock to Tzfat. Rabbi Shaul Leiter, Executive Director of the Ascent organization (see sidebar, p. 22), explains: “The first Chabad Rebbe, the Alter Rebbe, famously said that the difference between Kabbalah and Chasidut is that Kabbalah takes people’s heads and puts them in the heavens, while Chasidut takes the heavens and puts them into people’s heads.”

Wellsprings for the Future

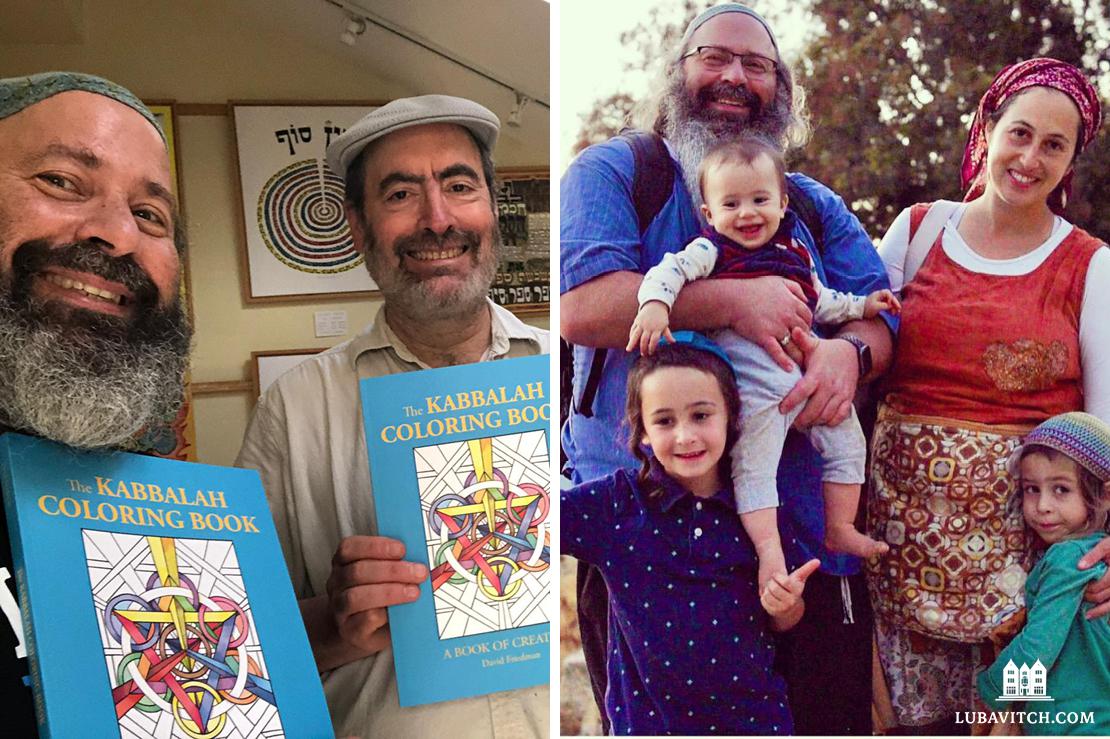

Zev, now 53, is married with three children and calls Tzfat home. “This is where my soul belongs,” says the former Hindu enthusiast.

“Early on in my Israel journey,” he adds, “I received a little red Tanya, and as I began to learn it, I saw that Judaism had real authentic, mystical wisdom to offer. It helped me let go of some of the Hindu beliefs I was clinging to.”

Right: Zev and his family

Several years ago, Zev was approached by Rabbi Sholom Pasternak, a Chabad emissary and director of a Tzfat yeshivah, to partner with Chabad to open a cafe “for the body and soul.” Elements Café, which offers vegetarian and vegan homestyle cooking, is now rated the number-one restaurant in Tzfat. Zev’s vegetarian culinary prowess comes from his years in the Hindu tradition and from his time serving thousands of free vegan, kosher meals at Rainbow Gatherings in the United States (in addition to providing hundreds of free tickets for people to fly to Israel to study Torah). Hosted in a Chabad-owned building, the cafe hosts a wide range of Torah classes that draw locals and visitors alike.

Covid-19 closures over the past year have been painful for the restaurant business, and for the Tzfat educational tourism industry as a whole. But even in lockdown, Tzfat residents never stop seeking. Zev took advantage of the downtime to partner with preeminent Tzfat artist David Friedman on the world’s first Kabbalah coloring book. He was also asked by Tzfat city council member Yohai Ezra to help run ReStarTzfat, a resource and community center that collaborates with Chabad and other organizations to serve Tzfat’s English-speaking residents.

“This last year has been a challenge, but there has been an attitude to never stop growing,” says Ascent’s Leiter, describing the dozens of students who chose to stay put at Ascent’s hostel during lockdown for weeks on end. “In a difficult year, we tried to focus on the points of light. The pause has allowed many to turn inward and really learn about their spirituality.”

The slow return to normal life brings excitement for new possibilities. Rabbi Kaplan notes a large uptick in interest on the part of Olim – immigrants to Israel – and particularly from members of the English-speaking Jewish Diaspora, in making Tzfat their home. “Hundreds of students, retirees, and families have used this crisis as a moment of introspection and are realigning their values with more spirituality. We are trying to keep up with demand.” This summer, Tzfat will open its first Chabad center specifically catering to English-speaking residents (as opposed to visitors).

Zev is optimistic. “There is a unique energy being born from this dark winter, and Tzfat is now entering a new, creative spring. People are so happy to see one another and connect.”

Kaplan recalls one young yeshivah student who arrived in Tzfat eager to spend a year learning there. The student was shocked at how small the city was. Considering the number of scholars, great rabbis, authors, and artists that make up the broad tapestry of Tzfat’s contribution to Jewish life, the student expected to find a bustling metropolis. “Tzfat has an outsize impact on Judaism around the world,” says Kaplan. “It is the city’s soul that captures hearts.”

*Name changed to protect the IDF soldier’s privacy.

This article appeared in the Lubavitch International Magazine – Summer 2021 issue. Special thanks to Derher Magazine for sharing information related to Safed. To subscribe and gain access to previous magazines please click here.

Matthew Hall

This was very interesting. SHALOM thank you.