In the Spring of 1977, I was working on my PhD in English literature, at the State University of New York at Buffalo when I decided to take a semester off to live and study in Crown Heights, Brooklyn at the Chabad Lubavitch world center. I was a spiritual seeker, and the Chabad rabbis in Buffalo had begun to connect me to Judaism. I wanted to try living it fully immersed—to test out its truth.

My mother met this announcement with deep concern and chagrin. I risked, she warned, being swallowed up in a backward community that had room for women only in the kitchen. I would be throwing away my academic career.

She was the youngest of eight children of devout Orthodox parents, Shmuel and Freida Katzin, who emigrated to Chicago at the turn-of-the-century from a small town near Kovno, Lithuania. She told me that at her father’s funeral in Chicago, in the late 1930s, he was praised as one of “the last of the real talmidei hachamim [Torah scholars].” Alas, that was not something he was able to pass down to his Americanizing children in a time of assimilation and economic stress. “He couldn’t fight America,” she said.

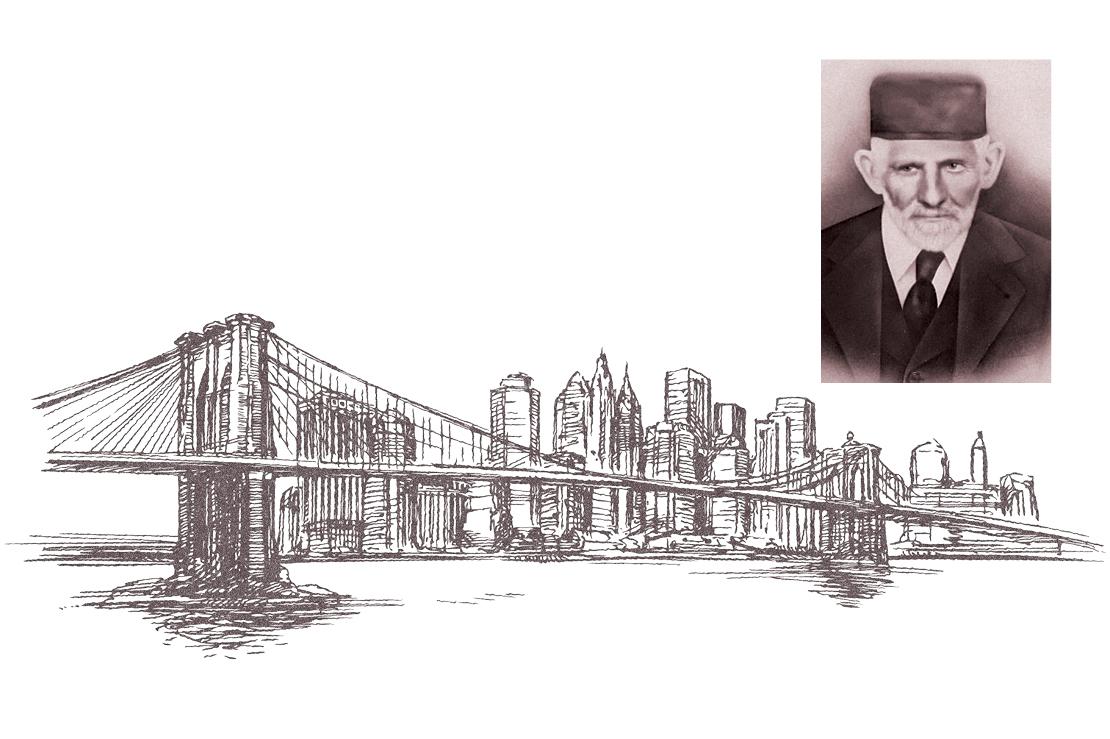

After two months of my living in Crown Heights, my mother bravely ventured to Brooklyn from Chicago to see what had become of her daughter. I sensed her discomfort at seeing masses of black hatted, long-bearded Chasidim and bewigged women. But she was a composed, polite and gracious woman. She began to enjoy meeting my friends, and the Lubavitch families to whom we were invited for the Shabbat meals. They did not at all fit her fearful stereotypes.

On Friday night, we stood in the women’s section of the large, crowded central Chabad synagogue, known as “770.” When the Rebbe appeared, making the long walk from his office to his place near the Holy Ark, she turned to me and said, “What a beautiful and dignified man!”

On Sunday afternoon, before her departure, I said to her: “Let’s go stand in the little alcove near the front door of 770. The Rebbe goes out of his office there to pray Mincha, the afternoon prayer, every day with the yeshiva students across the hall. People who are traveling come to get his blessings.” She agreed.

There were about a dozen people gathered in the small space. I positioned her in front of me for a better view. The Rebbe came out, passing closely by our small knot of people, on his way. The short prayers ended. I glimpsed him again close by, returning to his office. I saw his head turn towards our group and softly say something, which I didn’t understand, then continue on, and disappear.

My mother turned around towards me, and as she did, I saw tears streaming down her face.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, quite concerned. My mother, who raised my brother and myself alone after my father died in 1959, was not a person who cried easily and especially in public.

But now the tears were quietly flowing down her reddened face.

“Are you okay?” I asked again.

“Yes.”

“Why are you crying?”

“I don’t know… He turned to me and said, ‘Fohrt Gezunterheit.’ That’s what my father used to say to me when I would go on a trip. It means ‘Travel safely—go in good health’ in Yiddish.”

She daubed her tears with a tissue. It was time to go to the airport.

Long after, when we discussed that moment, she said to me, “I don’t know why I was crying. He touched something deep in my soul.”

After her visit, she decided that she wanted to keep kosher and Shabbat, as she had in her parents’ home. And she did.

My mother came to Brooklyn terrified that I was throwing my life away. But the memory of a simple Yiddish phrase that her father would say to her when she traveled, spoken quietly by a man whose face and being embodied the world of Torah of her father, reconnected her to her father, to Torah, and to her deepest soul.

Susan Handelman is Professor Emeritus of English Literature at Bar-Ilan University in Tel Aviv, Israel. She is the author of many books and articles including The Slayers of Moses: The Emergence of Rabbinic Interpretation in Modern Literary Theory, and Fragments of Redemption: Jewish Thought and Literary Theory in Scholem, Benjamin and Levinas.

This article appeared in the Spring-Summer 2023 issue of the Lubavitch International magazine. To download the full magazine and to gain access to previous issues please click here.

Be the first to write a comment.