“Said Rabbi Judah the Prince, ‘[G-d says:] So great is the virtue of peace among the Jews, that even when they are idolatrous, if peace reigns among them, I cannot hurt them.’” (Midrash Rabbah)

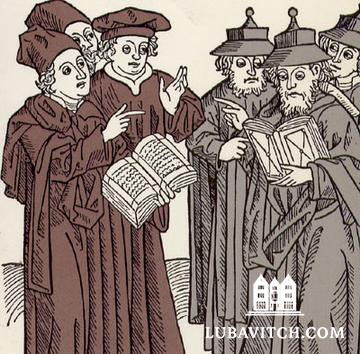

When, back in the middle ages, a Jewish convert to Christianity brought his grievances against the Jews to Pope Gregory IX, his complaints led to the famous Disputations of 1240. Four rabbis were forced to stand trial in defense of the Talmud against Nicholas Donin’s accusations.

The rabbis roundly won the dispute, but the repercussions were disastrous: The Talmud was condemned, and on June 17, 1244, twenty-four wagons loaded with manuscripts of the Torah and the Talmud were thrown into the fire, burnt in the streets of Paris.

Betrayal of this sort ranks at the very bottom of human vices. The idea that a member of the “tribe” would fuel the flames of anti-Semitism which gave the Jews—always at the mercy of the church—no peace, is, arguably, an irredeemable offense.

Nowadays, such activity often takes place under the guise of politically correct pretenses. Possibly those who make common cause with Israel’s enemies believe that we are secure enough to sustain this kind of internal rupture. Perhaps they think that fidelity to family is an irrelevant value in these progressive times. Or maybe they don’t even feel themselves part of the family.

But this chilling insouciance toward the fate and future of the Jewish people bespeaks a failure on the part of the community as well. For if we are responsible for one another, then we are responsible for our kin who stand apart from the community, disconnected from and indifferent to the wellbeing of the Jewish state and the Jewish people. We are responsible for this failing that exposes us and endangers our security.

The Megillah does not tell us this explicitly, but some commentators derive from Haman’s words to King Ahasueros a climate of disunity among the Jewish people: “There is a certain people scattered and divided among the nations. . . .”—a condition, say the sages, that put the Jewish people at a constitutional disadvantage, making them susceptible to Haman’s scheme of Jewish annihilation.

We don’t know the nature of the disunity among the Jews during that period of Jewish history, but to be sure, it was not about the community’s unwillingness, as some complain, to entertain disagreement. The Jewish people have a long tradition of fierce polemics. The Talmud itself is a rarefied repository of contentious debate and theoretical wrangling between Israel’s great sages. Two Jews, three opinions, and hair-splitting is a thriving Jewish pastime. But only when we argue with one another for the sake of Heaven.

Whatever may have divided the Jews during the Purim saga, Esther, the Megillah indicates, assessed the situation and quickly discerned her people’s weakest link that Haman hoped to exploit. In her response to Mordechai upon learning of Haman’s plot, she says: “Gather the Jews and fast for three days . . .” Fasting would not be enough. The Jewish people, she told Mordechai, must come together and repair the fissures that weaken us against our enemies.

When we are motivated by a love for the transcendent values of G-d, Torah and the Jewish people, our differences bolster us in the face of assault. But there is no such love among Jewish activists who work to punish and demonize Israel on the world stage as our enemies look on gleefully. When stabbing Jews has become a free sport that no longer makes headlines, and questions about Israel’s right to exist are bandied about as a legitimate issue for debate, we are right to feel outrage.

We are right to be ashamed that there are Jews who choose to remain silent, right to be appalled that some would go so far as to lend a hand to our enemies. Our disquietude is not without cause. Still, Mordechai’s promise to Esther echoes with comforting resonance: were she to remain silent at this time of crisis, he promised, “deliverance will arise for the Jews from another place.” We believe this to be true today as well, but we cannot ignore the disunity that diminishes us as a nation. We must reach even those on the far periphery who have lost their sense of place and belonging within the family of Israel. This may be our greatest challenge today.

Today, we need to support Jewish leaders who nurture Jewish unity and pride wherever Jews feel threatened or alone. Especially on college campuses where anti-Semitism and anti-Israel activism now run rampant, these efforts are critical, and because of them, many Jewish students have chosen to identify proudly, and speak out fearlessly. With dedication and commitment, we can achieve, as Esther did in her day, a positive reversal in the life of our people.

Happy Purim!

Be the first to write a comment.