“My zaidy called it ‘di heiliger Shabbos’ (the holy Shabbos); my father called it the Shabbos; I call it ‘the Sabbath,’ my children call it ‘Saturday,’ and my grandchildren call it ‘the day before Super Bowl Sunday’.”

This pithy anecdote describes a tragic trend among Jews who came over from the Old World and failed, for whatever reason, to transmit di heiliger Shabbos to the younger generation. It tells of its disappearance not only from the lived experience — but also from the lexicon — of Jews who have assimilated into secular culture.

But Shabbos is embedded in the Jewish soul. Some people hold on to it at all costs, while others come back to it after generations of nearly losing it. These are the personal Shabbos stories of an eclectic group of influential personalities.

Part 7/7

It was the mid-1960s, and my family lived in a village outside of Moscow. I was the only religious Jewish kid in my class — a perfect target for bullies. “Abramchik,” my classmates called me.

My parents devised ways of always staying one step ahead of the authorities. Things like getting matzah for Passover, convening with a group of Jews for a minyan, shofar blowing on Rosh Hashanah, and even keeping Shabbos required covert, strategic planning, always dangerous.

For as long as it was possible, my parents kept me home, and my grandfather taught me the Hebrew Aleph Bet, Chumash, Mishnah, and Talmud. By the time I got to second grade, my parents had to enroll me in the local public school. But first, because Shabbos was a regular school day, my father took me to a doctor and somehow convinced him to write a note to the school that I needed to have a second day off every week in addition to Sunday. “Keep him home on Wednesdays,” the communists said. My father insisted that it had to be Saturdays and managed, somehow, to get his way.

When Shabbos came in early on Fridays during the winter months, and school wasn’t out until 4:00, I had to come up with different excuses for leaving school early. That worked for a while, but on one particular Friday, I ran out of excuses and couldn’t get permission to leave. I thought I would just sit out the rest of the day, listening to the teacher as she spoke. To my terrible dismay, the last class was a drawing class.

I just sat there without touching the crayons.

My teacher began to scold me. I don’t remember exactly what happened. She may have forced the crayons into my hand, or threatened me in some way. I was an eight-year-old kid, and I became very distraught by the pressure. But I wouldn’t draw on Shabbos so she finally got someone from an older grade to fulfill the assignment on my behalf.

Afterwards, she went on a long tirade, lecturing me in front of the class about the stupidity of religion. Yuri Gagarin, the Russian cosmonaut — the first human to travel to space — was a national hero. “Gagarin didn’t find G-d when he was up in the heavens,” she quipped. Then she began to mock religion. I soon realized that she had no idea that Christianity and Judaism were different religions, and I remember being amused that in her ignorance, she thought she was punishing me by railing against Christianity.

After the incident, my father was called to a meeting with communist authorities who threatened to remove me from my family if this continued. This was terrifying for all of us, and my father was desperate to get us out of Russia. He fought his way with a lot of chutzpah through an intimidating communist bureaucracy. Miraculously, a few months later, we got our exit visas.

We left in a hurry without saying a word to our neighbors or the school. My aunt told me later that when the school learned that we emigrated, they declared me a traitor to the USSR. They threw my bookbag and whatever else I had left in my locker into a bonfire they’d made for the occasion.

In the winter of 1967, we arrived in Israel. It seemed like a different planet. That first Shabbos, my mother was shocked that the family hosting us didn’t draw the curtains when they lit candles. And on Shabbos morning, when our host put on his tallis as he got ready to go to shul, my father couldn’t relate — to wear a tallis out in the street?

It took us all time to shed the fear, to stop looking over our shoulders. But for me, having grown up afraid simply because I was Jewish, the sight of kids being overtly and unself-consciously Jewish out in the streets was incredibly exciting.

My childhood years in Russia didn’t give me the light, joyful Jewish experience we want for our children. But they gave me perspective. My parents’ and my grandparents’ commitment to Yiddishkeit was defining.

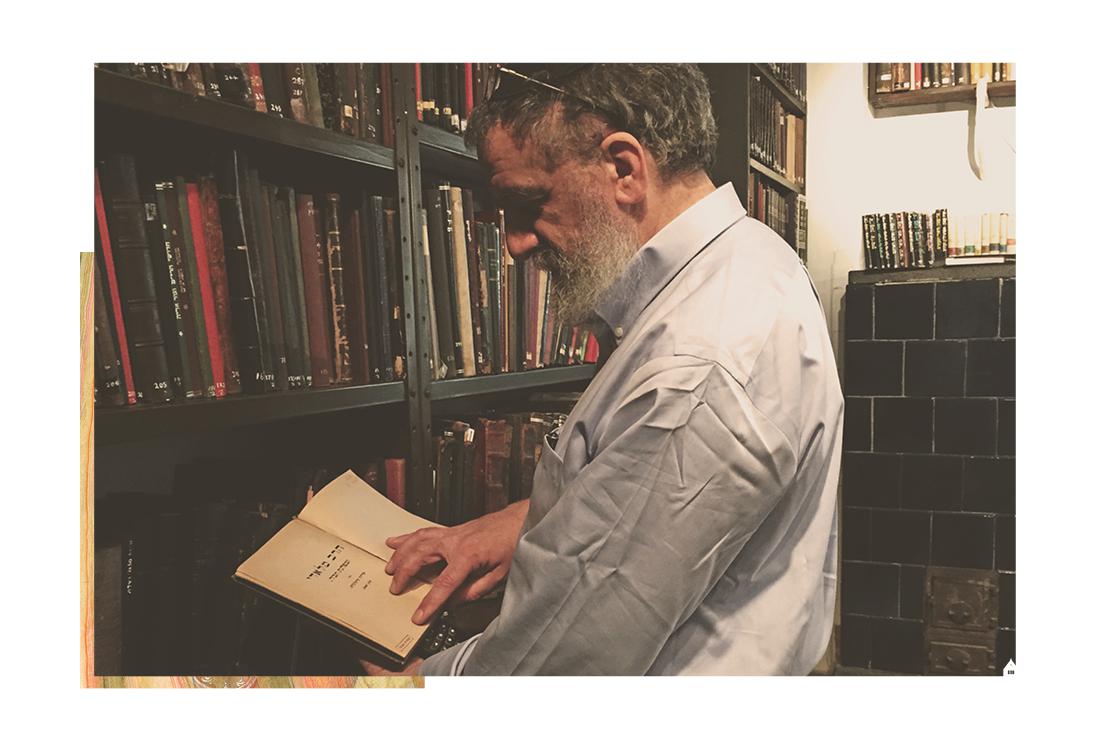

Rabbi Dovid Olidort is the Senior Editor at Kehot, the Chabad Publishing House.

This article appeared in the Fall 2021 issue of the Lubavitch International magazine. To download the full magazine and to gain access to previous issues please click here.

Be the first to write a comment.