The most that we can understand about G-d

is that we cannot understand him,

as the wise man said:

The sum total of what we know of Thee

is that we do not know Thee.

Behinot ha-Olam (The Examinations of the World), a didactic poem on the unknowability of G-d by Jedaiah ben Abraham Bedersi (Jedaiah haPenini).

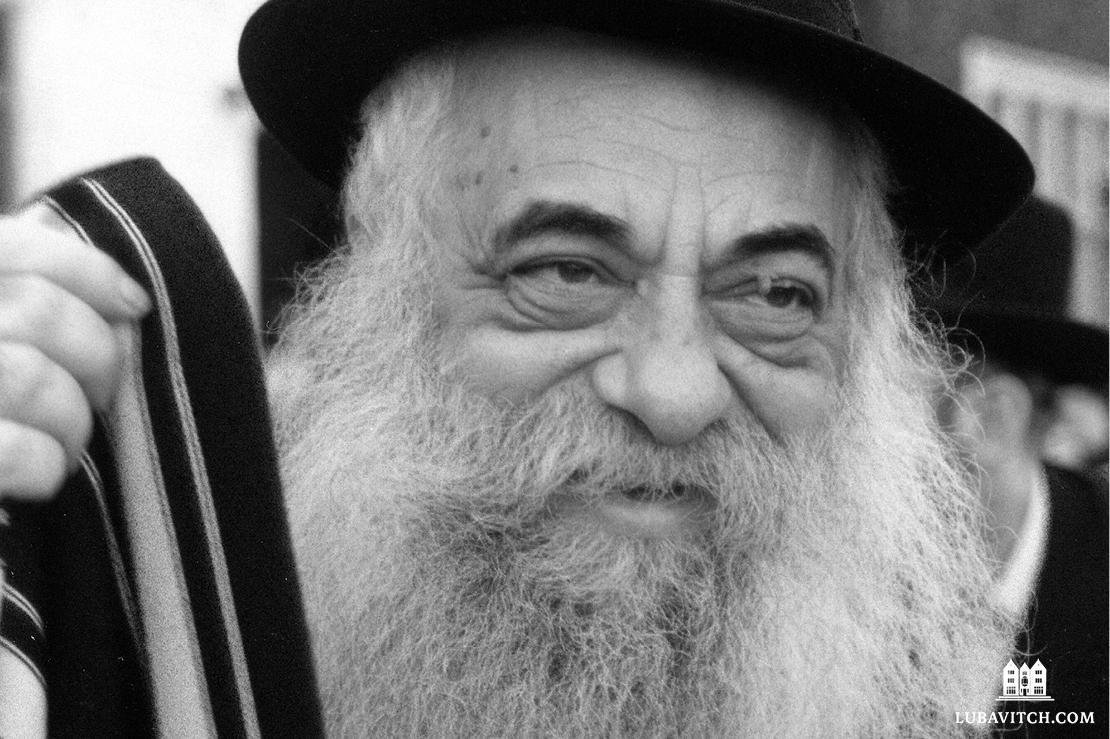

Rabbi Yoel Kahn, who passed away this past July (6 Av) at age 91, was the wise man of Chabad Chasidism. The master redactor and interpreter of Chasidic texts and deeply devoted to the teachings of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, he shaped the contours of Chabad scholarship over the course of seventy years, introducing a new way of approaching a discipline that had theretofore been beyond the grasp of most.

Rabbi Kahn was born in Soviet Russia in 1930 to Refoel Nachman and Rivkah Kahn, members of the underground network of Chabad Chasidim who worked to sustain Judaism behind the Iron Curtain. When he was five years old, his family emigrated to Israel, which was then under the British Mandate.

His lifelong career began in the twilight year between the passing of the sixth Chabad Rebbe and the ascendancy of his successor, the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson. The star yeshiva student came in 1950 from Tel Aviv to New York, where his brilliant intellectual gifts and prodigious memory were quickly noted. He became the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s exponent, eventually leading teams of scholars in the transcription and redaction of the Rebbe’s talks.

Applying his extraordinary analytical mind, Reb Yoel, as he was known, uncovered unifying principles in doctrines such as G-d’s oneness and the divine soul. With his precise use of language and his exquisite attention to nuance, he distilled and concretized theoretical ideas, organizing them in a consistent and logical system. His teaching of Chabad’s primary text, the Tanya, opened a gateway for students to make meaning of the esoteric world of Chabad.

Reb Yoel had an uncanny sense of his audience. The consummate teacher, he took the questions of a young student as seriously as those of a learned scholar, communicating difficult content to each at their level with great patience, often through parables and stories. Men and women grappling with Chabad’s perspective on theological issues turned to him for clarity, coming away with a sense of a universal truth that moved them to think and to live differently. “He believed that we are capable of reaching a higher state of being, and he wanted to share that with others,” one of his students said.

Quintessentially unassuming and notably inattentive to mundane matters, Reb Yoel lived on a spiritual plane “five times removed from the average person,” said another of his students. His brilliance was intimidating, but his deep humility and sense of humor made him approachable and beloved. He also had a finely attuned ear for music and melody, and was a repository of old Chabad nigunim. Students vied for a place in his classes or a spot at his legendary Shabbos table. Although he was known to sometimes respond with a sharp retort to insincerity, he generally preferred the longer route of an indirect takedown, patiently telling a story so that its message would land with gentle impact.

Reb Yoel edited over a hundred volumes of the Rebbe’s talks. In the late 1950s, the Rebbe assigned him the monumental task of compiling an encyclopedia of Chabad Chasidic thought. To date, eight volumes of Sefer Ha’Arachim-Chabad were completed, with entries such as the mystical meaning of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet; love of G-d; the infinite light of the Divine; the kabbalistic sefirot; and the oneness and unity of G-d.

***

When Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai died, the sages said wisdom ceased. When Rabbi Yehoshua died, they said the gift of council and deliberate thought ceased. With the passing of ben Zoma, they said that the exegetists ceased. Of Reb Yoel, the man who nurtured the golden age of Chabad scholarship, they may have said all of the above.

But the mashpia (Chasidic mentor) who brushed up against the very edges of knowledge would have said that the purpose of it all is to arrive at that self-effacing precipice where human knowledge ends, and the bond with G-d becomes possible. Perhaps then, the epitaph the sages would choose for Reb Yoel would be the words of the early poet: Tachlit hayediah shelo neda-acha, “The ultimate knowledge is the unknowability of the Divine.”

This article appeared in the Fall 2021 issue of the Lubavitch International magazine. To download the full magazine and to gain access to previous issues please click here.

Be the first to write a comment.