Translated by Ruth Wisse

Published by The Tikvah Fund and Toby Press

The year is 1948. Two Holocaust survivors run into each other on a Paris subway. Though each had assumed the other was killed in the Holocaust, they waste little time exchanging questions about wartime experiences or polite inquiries about the well-being of family and friends. Instead, the two fall back into an argument they had begun many years before, in the period preceding World War II. Both are graduates of the Novardok yeshiva in Lithuania, and their argument is intellectual, philosophical, and also deeply personal. They debate the question of how a Jew should relate to the world around them. One believes the world outside of Judaism is rich with insight and enlightenment. The other maintains that the Torah is the only source of meaning in this life, and all other endeavors amount to nothing but vanity and self-destruction.

Chaim Vilner, a left-leaning Yiddish writer, admires secular humanist attempts to reform and improve the world. When he was younger, he was a student of Mussar, a Jewish movement that pursues spiritual and ethical perfection. He studied at Novardok, an extreme outpost of the Mussar movement where students would willingly engage in seemingly humiliating, self-abnegating behavior in order to break free from the physical world. Nearly all of the world of Novardok was wiped out during the Holocaust, with few surviving adherents. Hersh Rasseyner, Vilner’s interlocutor, is one of them.

For Rasseyener, the only path towards moral improvement is through actions—the fulfillment of mitzvahs—and not through lofty philosophical abstraction. In Rasseyner’s view, all of the wisdom of Western Civilization amounts to very little. After all, it did nothing to forestall the horrors of the first half of the twentieth century. As he tells Vilner: “You thought the world was striving to become better, but you discovered that is was striving for our blood.”

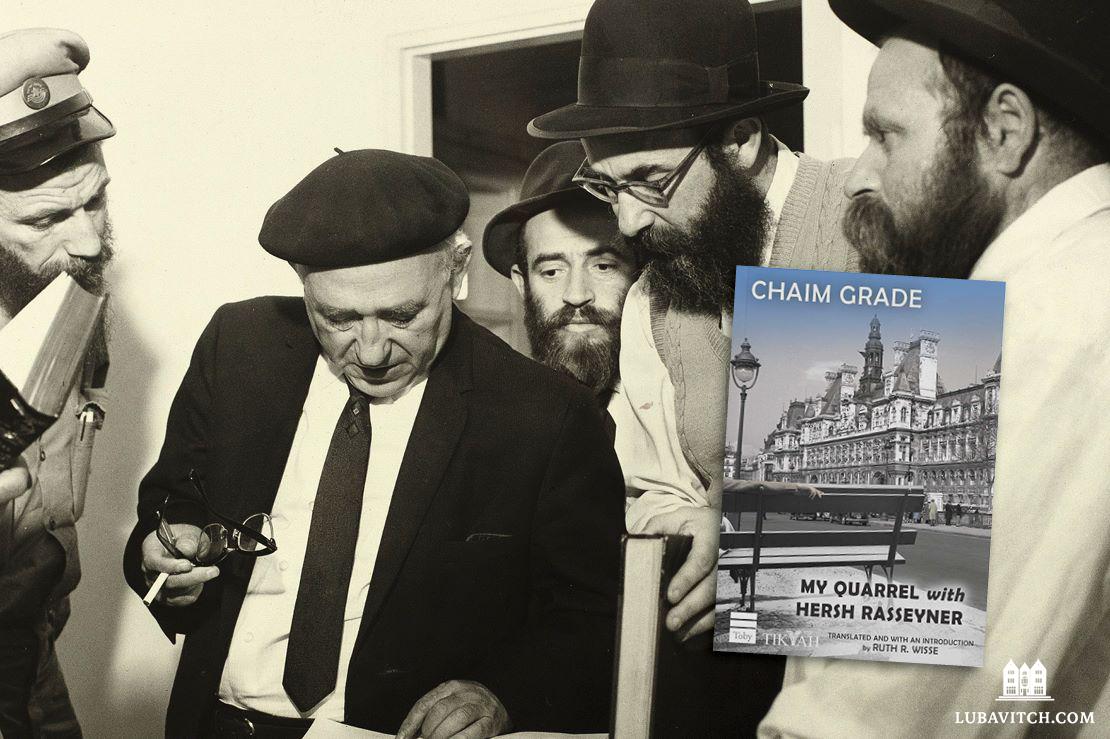

The substance of this argument forms the bulk of the iconic Yiddish story, “My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner,” first published by the Yiddish writer Chaim Grade (pronounced: grah-deh) in 1951. “My Quarrel” is a classic of Yiddish literature, due in large part to an early English translation by Milton Himmelfarb. This translation drew attention when it first appeared in Commentary Magazine in 1953. It was also canonized in Irving Howe’s famous anthology of Yiddish stories. Yet Himmelfarb’s elegant translation, accessible for an audience with minimal Jewish background, takes liberties with the original, downplaying many of Grade’s rabbinic or Jewish expressions, and even deleting some parts of the story entirely.

Enter Ruth Wisse, a scholar of Yiddish and Jewish literature, whose new translation of “The Quarrel” restores the Jewish texture of the debate while presenting a more complete version of the story. Wisse’s translation includes heretofore excluded passages, and also quotes many rabbinic phrases in their original Hebrew. The new edition, published by a partnership between Toby Press and the Tikvah Fund, even includes Grade’s original Yiddish text alongside the English. In doing so, this version highlights dimensions of Grade’s own Jewish identity that may have been less apparent in the story’s previous English incarnation.

Grade himself, in his biography and chosen profession, strongly resembles the maskil (enlightened) Vilner. He too spent time studying in Novardok and then abandoned the yeshiva, along with much of his religious observance—at least for a period of time. There are hints that the character Rasseyner is also based on a real acquaintance of Grade’s. Yet the story itself is remarkably even-handed, and one almost feels that, through Rasseyner, Grade allows himself to articulate certain truths that would have been unacceptable for him to express in his urbane literary milieu. This, in fact, is what makes the story so powerful and spiritual.

Rasseyner argues that the horrific experiences of anti-semitism during the Holocaust and throughout Jewish history prove that Jewish assimilation is doomed to fail. Even mild attempts at secularization, or moderation, of “lightening the burden” of Jewish tradition, are futile in Rasseyner’s view. As he says, “a half truth is no truth.” In keeping with Novardok’s tradition of strident rebuke, Rasseyner does not hesitate to attack Vilner’s sensibilities, his career, or even his personhood: “Instead of looking for solace in the Master of the World and in the Community of Israel,” Rasseyner says, “you’re looking for the glass splinters of your shattered dreams. And as little as you’ll have of the world to come, you have even less of this world.”

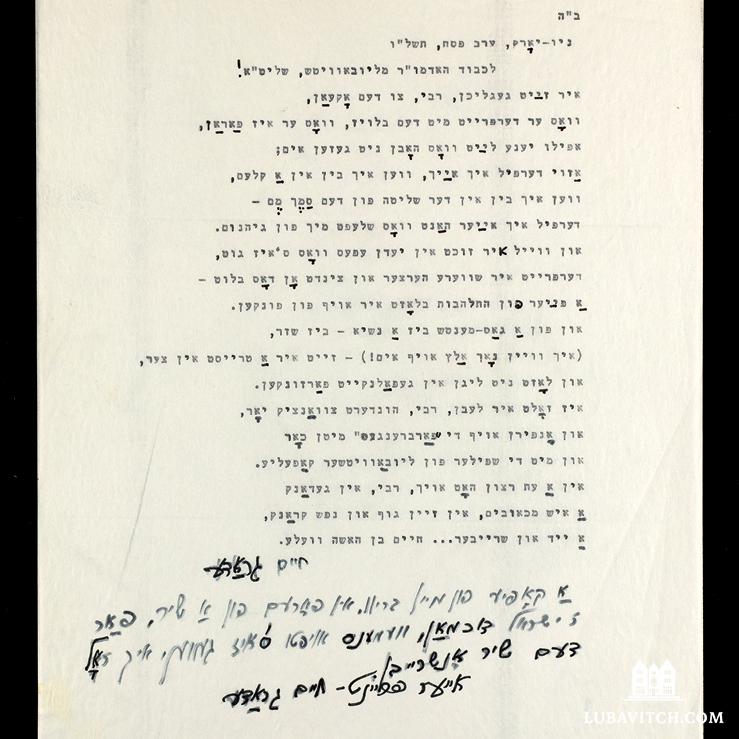

Written in Yiddish rhyme, Grade is effusive in his praise of the Rebbe for—among other things—his impact on the Jewish people, and personally, “for drawing him [Grade] out of dark places.” He wishes the Rebbe long life at the helm of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement.

One particularly illustrative section, which was excluded from the Himmelfarb translation and is restored by Wisse, involves the only additional character in the story—a student of Rasseyner’s named Yehoshua who happens to come upon Vilner and Rasseyner in the middle of their debate. Rasseyner saved Yehoshua in the concentration camps and nourished him back to life physically and also spiritually, through Torah learning. Though he’s initially respectful, Yehoshua turns critical and angry at the bareheaded Vilner for his life choices. In her introduction, Wisse suggests that Grade wrote Yehoshua as a critique of the ultra-Orthodox, especially when they lack maturity and perspective. Yet Yehoshua’s fiery presence in the story also reflects a different light on Rasseyner himself, who appears more gentle and mature by contrast.

Through Yehoshua’s moving account of how Rasseyner saved his life in a concentration camp, we see Rasseyner’s ideals in action. We are allowed to experience, and not just intellectually absorb, how for Rasseyner, religious fervor and human empathy go hand in hand. At one point in their conversation, Vilner asks Rasseyner if he remembered to daven Mincha, the afternoon prayer, that day. Rasseyner tells him that, even if he had not, “I wouldn’t have left you.” Rasseyner may be critical and even harsh, but he is as uncompromising in his concern for Vilner as he is in his religious principles.

Still, while Wisse’s translation makes Rasseyner’s arguments more sympathetic than ever, Vilner continues to voice his part. He does not refute Rasseyner point by point, but rather appeals to the logic of those same arguments to make his own case for tolerance and inclusiveness. Vilner counters that Rasseyner’s dismissal of secular, enlightened Jews is wrongheaded. Many of these ordinary assimilated Jews worked hard, tried to provide for and protect their families, and suffered in the catastrophes of the era just the same. Then Vilner extends a similar defense to the non-Jewish world, not the great artists and thinkers—who, he seems to implicitly cede to Rasseyner, did not do much to avert moral catastrophe—but two righteous gentiles, an elderly Pole and a Lithuanian, who quietly risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. “Where in your world,” Vilner asks Rasseyner, “is there a corner for these two old people?”

In the end, Vilner concludes that despite all the theological doubt and confusion wrought by the Holocaust and Communism, his love for his fellow Jews has become “more anxious and deeper.” While his quarrel with Rasseyner allows Vilner to clarify and outline everything that he objects to about religious Judaism, in the process of arguing he discovers that his affection for his fellow Jews has only strengthened despite, or perhaps as a result, of this extended debate. Vilner turns toward Rasseyner much in the way that Rasseyner turns toward him, and says, “I love you with all my soul.” Before they part, the supposedly secular Vilner tells Rasseyner, “I say to you as the Almighty said to the Jews assembled in Jerusalem on the Holy Days: ‘I want to be with you one day more, it is hard for me to part from you.’”

“My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner” reads less like a “war” and more like an attempt at integration. While the fiercely logical debate takes place between two Lithuanian yeshiva graduates with a high-level Talmudic background, there is something distinctly romantic, and one could also say Chasidic, about the holistic mode that the story and the arguers embrace at the end.

In her wonderful introduction to the story, Wisse recounts a debate over the translation of the story’s title, “Mein Krig Mit Hersh Rasseyner.” Should “Krig” be translated as the technically-correct “War” or the gentler “Quarrel?” Ultimately, the story reads less like a “war” and more like an attempt at integration. While the book’s fiercely logical debate takes place between two Lithuanian yeshiva graduates with Talmudic backgrounds, there is something distinctly romantic, and one could also say Chasidic, about the holistic mode that the story and the arguers embrace at the end.

Interestingly, this pivot is anticipated elsewhere in the story in a short, infrequently cited exchange that is left out of the Himmelfarb translation, but which Wisse thankfully includes. Even before they begin to quarrel, Vilner notices that something has changed about Rasseyner’s once-harsh mannerisms. “Reb Hersh,” he tells him, “you’re not speaking like a student of Novardok, but more like a Chasid of Lubavitch who is studying the Tanya.”

Rasseyner answers that, for skeptics like Vilner, Chasidism and Mussar may seem like opposing points of view. But, on a deeper level, “they are one and the same…when I feel overpowered in the struggle of life, I study Mussar. And when Mussar leads me too far into gloom and seclusion and tears me away from the community of Israel and love for my fellow Jews—then I turn to Chasidism.”

This passage is interesting because it broadens Rasseyner’s worldview beyond the confines of the Novardok yeshiva and positions him as a representative of the diversity of religious Jewry. Perhaps the fact that Chasidism now features more prominently in his worldview is part of what ultimately allows Rasseyner and Vilner to relate to one another in a manner that they were unable to before.

In fact Grade himself, despite his complicated religious identity, and his Lithuanian yeshiva background (he was also close with Rabbi Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz, the Chazon Ish) seems to have harbored a warm spot for Chabad Chasidut. After Grade’s passing, his close friend, the late Chasid, Yisroel Duchman, wrote a remarkable obituary for Grade in the Algemeiner Journal that detailed some of this Lubavitch connection. Duchman spoke to Grade’s time in Kfar Chabad after the war, as well as to his unique relationship with the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

Wisse’s translation includes heretofore excluded passages, and also quotes many rabbinic phrases in their original Hebrew. The new edition, published by a partnership between Toby Press and the Tikvah Fund, even includes Grade’s original Yiddish text alongside the English. In doing so, this version highlights dimensions of Grade’s own Jewish identity that may have been less apparent in the story’s previous English incarnation.

Like his characters Rasseyner and Vilner, Grade endured many difficulties during the Shoah. His wife and mother were murdered by the Germans, and his childhood community of Vilna was decimated. Even after having survived, Grade also encountered coldness from former friends and acquaintances from his Novardok yeshiva past, precisely when he needed warmth. Duchman quoted Grade as having said, “in Kfar Chabad I was warmed.”

In reflecting upon his relationship with Grade, Duchman made the following observation, which could easily be applied to “My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner” as well: “When we met we used to talk about Jews and Judaism and about the world at large. We didn’t always agree with one another and oftentimes we argued, but our differences of opinions never detracted from our friendship, and until his very last day, Grade remained a close and loyal friend.” In addition to raising many fascinating theological issues and debates, “My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner” explores the way in which two mens’ religious sensibilities (or lack thereof) are inextricably bound up with their feelings toward one another.

“My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner” ends at a kind of impasse, with neither side a clear victor. Chaim Grade’s own life, however, ended with his instructions to be buried in the beautiful woolen tallit with which he prayed each day—a final hint as to which side his heart and soul ultimately belonged.

This article appeared in the Spring-Summer 2023 issue of the Lubavitch International magazine. To download the full magazine and to gain access to previous issues please click here.

Debra S Michels

Baruch haShem for Ruth Wisse, and to Chaim Grade for the strength and hard work it took, to write this story. And thanks to you for letting us know about this new translation!!