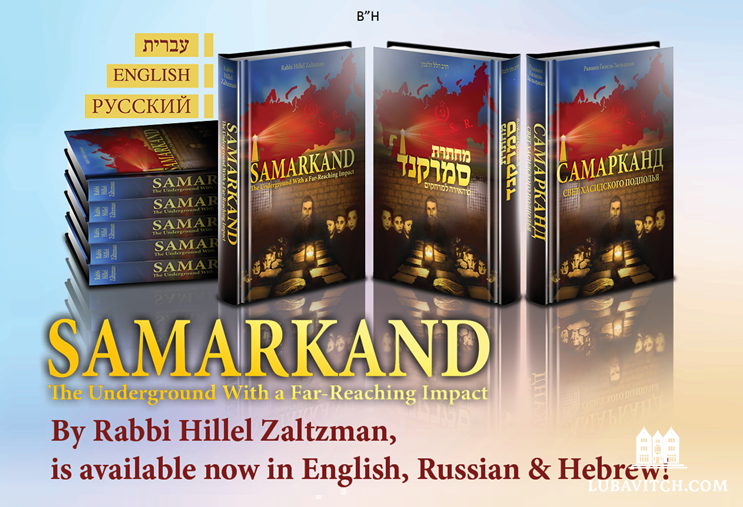

Samarkand: The Underground With a Far-Reaching Impact

By: Rabbi Hillel Zaltzman

Chamah Publications|732 pp.|Available on Kehot.com

In the 1964 Presidential election, Republican candidate Barry Goldwater is famously remembered as quoting the Roman orator, Cicero, in the following bold assertion: “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice! Moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue!” The resonance of this statement with our current sensibilities, despite the fact that it has its origins many centuries prior, only attests to its capturing a cardinal truth of the human endeavor. That, while avoiding fanaticism and extremism is generally a good practice,when faced with tyranny, such an attitude is both cowardly and self-destructive.

And quite rightly, in human history, those who were willing to stand up against oppressive governments in the name of minority rights are lauded as heroes and their causes now integrated into the fabric of modern life. The American founding fathers, the leaders of the Civil Rights movement, the righteous gentiles who hid Jews during the Holocaust—all of these were political dissidents, acting, at the time, with what you might call fanaticism. But they are properly understood to be heroes.

Interestingly, those who stood up against the oppressive Soviet Communists are not the first to come to minds of modern Americans in such a discussion of heroic figures. In fact, Communism itself is often not thought of (or taught) as quite such a tyrannical evil. And shockingly, in a recent poll, nearly 25% of Americans either think Communism is morally superior to our current form of government or are “not sure” whether or not it is. For a political system that murdered 20 million of its own citizens when implemented in Russia, and millions more in China and elsewhere, that’s an astonishingly high approval rating.

The result of this sympathy with Communist ideals translates into a lack of understanding of and sympathy for those who were willing to stand up against it. You don’t see the faces of Soviet dissidents painted on the “Heroes Wall” at public elementary schools. You don’t hear whispered concerns over the fact that soon those who suffered under Soviet Communism will all die and there will be no one to transmit their story. In fact, you don’t hear much about them at all.

And so, Rabbi Hillel Zaltzman’s recently translated memoir, Samarkand: The Underground with a Far-Reaching Impact, that chronicles his life under the oppressive, totalitarian regime of Soviet Russia and the steps he and others took to ensure the survival of their religious ideals and practices, is a precious rarity. It shares the story of how, in a tiny corner of the Soviet Union, Samarkand, Uzbekistan, a small group of dedicated Chabad-Lubavitch families inspired and encouraged by the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn and subsequently, the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, managed to create an underground network that would ultimately succeed in bringing the teachings of Torah to over 1,500 young Jews under the radar of the ever-present KGB. Samarkand offers a window into the unique experience of those who managed to keep Judaism not just alive, but flourishing, under Communism. It shows the extreme oppression of totalitarianism, which unlike authoritarianism or other dictatorial governments, attempts to suppress all minority views.

The result of which is, in the period of a few generations, the near destruction of any shared communal belief system other than the mandated government ideology. So, in a world where the Chinese Communist government casually prohibited married couples from having children leading to the elimination of unwanted female babies, European countries are enthusiastically banning Jewish practices of circumcision and ritual slaughtering, and America’s academics are cowed into silence lest they teach something deemed “triggering,” such a story is not just of interest, it speaks to a moral imperative.

Unlike much of the literature of the present era, replete with overwrought prose and tired imagery, Samarkand wastes no time in telling its story: the story of people. These were people who, despite the great physical and psychological struggles of living under Communism, displayed courage and determination of Maccabean caliber. While in much of Russia survival under communist totalitarianism turned men into small craven animals, in Samarkand, giants seemed to walk the earth.

One of the most compelling characters is that of Rabbi Mendel Futerfas, famed Chabad-Lubavitch mentor and activist who clandestinely worked on behalf of Russian Jewry, and whose presence in the town of Samarkand, though brief, had a deep impact on those he dealt with. The story of Reb Mendel, as he is affectionately referred to by the author, and the great personal sacrifice he undertook to save the lives of his fellow Jews, epitomized the unfailing faith and dedication to the Jewish people chronicled in Samarkand.

At the end of World War II, when the Russian government allowed Polish citizens to exit the country, Reb Mendel saw an opportunity to rescue his fellow Jews from the grips of Communism by producing false Polish passports. At a certain point it became clear to him that the KGB was aware of his work, yet he refused to cease his activism. This would ultimately mean that he would be arrested, tortured and sentenced to death by the KGB. He would later describe to the author the KGB’s brutal and twisted method of interrogation:

He recalled how the door of the interrogation room would open, and a detainee would be summoned by his last name. The man would stand up, wailing and crying, not knowing what fate awaited him in the next room. Frequently, after incessant screams and sobbing from the interrogation room, a gunshot would be heard, followed by total silence.

In the case of Reb Mendel, however, the interrogation took a decidedly different turn. When they discovered that they could not break his spirit with beatings and torture, they tried psychological means to get his cooperation:

“You’re sentenced to death, you know. But if you were to cooperate, we could save you by giving you a prison sentence instead…”

Reb Mendel was unmoved:

“You know that I believe in G-d. I have no doubt that if He wants me to die, even if you were to release me now, I could be run over and killed by a car as I leave here. But if He wants me to live, you will never succeed in killing me.”

And it seems that G-d wanted Reb Mendel to live, because shortly after his death sentence was issued, a telegram arrived from Stalin with instructions to commute unfulfilled death sentences to twenty-five years in prison. Indeed, in 1953 when Stalin died and Khrushchev took over, Reb Mendel was one of the many political prisoners who was released. Though it would still be more than a decade before he would be able to leave Russia and reunite with his family, Reb Mendel was a “free man” and would eventually make his way to Samarkand to help the author and his compatriots.

When the author first met Reb Mendel he asked him a question that had been plaguing him and his peers. Was it possible, they wondered, to dedicate oneself to the needs of the community before one had spent sufficient time in one’s personal spiritual growth? And despite the fact that such dedication to the needs of his fellow Jews had condemned Reb Mendel to brutal torture, back-breaking labor, and ultimately decades long separation from his family, his reply was unwavering:

“If the prophet Eliyahu [Hanavi] himself comes to you and says that there’s no need to involve yourself with your fellow Jew, tell him, ‘You might be Eliyahu Hanovi, but we’re still not listening to you,’ and continue to assist others.”

Such was the “extremism” of the Samarkand underground.

Samarkand shares hundreds of unique and heroic stories about Chabad-Lubavitch life in the Soviet Union. But in some sense, this book isn’t about heroes at all. Rather, it is about the heroic abilities that exist within ordinary people.

Rabbi Zaltzman relates that when he arrived in the United States in 1971, together with a group of emigrants from Samarkand, he was invited to meet with the great Torah scholar and halachic arbiter, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein. Upon describing the extreme measures they went to in order to maintain a Jewish life in the Soviet Union, Rabbi Feinstein asked them:

“How could you survive under these conditions?!”

“Did we have a choice?” they answered.

And interestingly, in the entire 700-plus pages of Samarkand, the issue of “choice” never comes up. Because it was clear to the Jews of Samarkand that to choose avoidance of hardship, to choose to follow the modern trends of their time, to choose to pursue a life of success to the extent possible in the Soviet Union, would have absolutely precluded a choice to remain Jewish.

In our present era, when the ability to choose anything is asserted like a G-d given right, but yet the responsibility for such choices are shirked without thought, such a perspective is refreshing. It confirms the truth that is becoming increasingly uncomfortable in today’s society:that our lives must be lived as a whole, that the choices we make today determine the peoplewe will be tomorrow, and that it is those seemingly small, but incredibly difficult choices that we make on a daily basis that shape the content of our character.

When Reb Mendel Futerfas first arrived in Samarkand, dejected at the thought of continuing to remain under watchful and stifling Communist government, the author shared the following thought with his guest: “Just by being in Samarkand,” he related enthusiastically, “one is uplifted.” And though Reb Mendel was doubtful then, upon departing from Samarkand he confirmed, “Now I see there’s some truth in your words.”

As we look forward to a world that seems to hold no future, it is Samarkand’s message of extreme faith and dedication, the message that succeeded in bringing Judaism out of darkest Russia, that has the power to lift us and carry us forward.

Be the first to write a comment.