The Upper East Side of Manhattan, one of the wealthiest ZIP codes in the United States, is known for its highly-regarded schools, and its sidewalks and playgrounds are filled with children. Mothers don’t always work full-time, and nannies and household help abound. Still, quiet assumptions related to childrearing govern life in this privileged enclave. One or two children per family is normal and expected, a third “status child” is not unheard of for some, and with four you are most likely a little weird, or a religious Jew (or both).

Chani Krasnianski is the director of Chabad of the Upper East Side and she’s rather confident that with nine children she has the largest family in the neighborhood. A Chabad family further south is a close second with eight children. Krasnianski acknowledges that it often feels like almost nothing in her community, including apartment sizes or tuition price tags, is designed for a family like her own.

In 2017, the birth rate in the United States dropped to an historic low average of 1.76 children for each woman in her childbearing years. The figure tends to fluctuate over time—but various studies estimate that current fertility rates are unlikely to return to a replacement ratio of two children anytime soon. This is an old story in Europe, where birth rates have been in decline for decades, and a rapidly aging population casts doubt on the future economic sustainability of the continent.

Historically, events such as war or famine may have been the primary causes for a dropping birth rate. However, the situation is rather different in the modern Western world. Ours is physically the healthiest and most affluent society that has ever existed, and, in some ways, raising children is also more convenient than it has ever been. Yet, children are increasingly perceived as a burden. Differences in the nature of modern life, changing expectations regarding marriage and gender roles, and perhaps some deeper social and religious trends are just some of the factors that are motivating many couples to opt out of having more than one or two children. And that’s if they have any at all. This, in turn, creates a kind of negative feedback loop in terms of the way that society views children, the amount of children one encounters in public spaces, and of course, on the average person’s motivation to organize their life around having them in the first place.

Among Chasidic or Orthodox Jews, families of seven or more children are not unique. But Chabad representatives like Chani largely do not live in sheltered religious enclaves, but rather in communities which harbor very different assumptions about having children. With this exposure comes an inevitable sense of disjunct, but also an opportunity. Large families which emphasize the joy, and the immense opportunity of bringing children into the world, may even present a kind of “counter culture” wherein commonly held truisms about the burdens of parenting might be re-evaluated or even overturned.

In his 2011 book How Civilizations Die, opinion writer David Goldman makes a powerful argument that links Western population decline with, among other matters, a crisis of faith. As Goldman has it, “If we do not see ourselves as continuing the lives of those who preceded us, nor preparing the lives of those who will follow us, then we are defined by our physical existence and nothing more. In that case we will seek to maximize our pleasure.” Economist Bryan Caplan, the author of Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids, takes a more pragmatic line. Western parents “over-parent” to such a degree, he argues, that is intimidating and financially draining for them to continue to expand their families even if they would like to do so.

In another 2012 book, The Case for Children, Chabad Rabbi Simcha Weinstein of Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute considers how Biblical wisdom regarding this matter is perhaps more relevant today than in the past, when fertility was hardly something one had much choice in:

Some might ask why G-d needs to command people to do something that not only guarantees the continued survival of the human race but also comes so naturally. However, I sometimes wonder if that long ago command to be fruitful and multiply was actually meant for us modern people, thousands of years in the future—a kind of message in a (baby) bottle that would wash ashore in our postmodern, post-parenting era. (p. 330)

Weinstein is a campus rabbi, and one major place where these questions inevitably play out is on the college campus. Indeed, in addition to its other functions, a university might be characterized as a place where individuals in their prime reproductive years put off starting a family. This is not a quirk of the university environment, rather it is a feature of it.

Miri Birk is the program director at the Chabad Center of Cornell University. Parenting, she says, tends to be far from the minds of the intelligent and idealistic students she encounters. When an undergraduate comes to college intending to become a doctor, he or she has a clear path: take certain courses, find relevant internships, apply by a certain time frame, etc. But for a student with distant dreams of starting a Jewish family, there is no path, no suggestions for when to date, whom to date, or places to consider career opportunities where such a goal might be more feasible. For an Ivy League undergraduate with hopes of changing the world, there may even be a sense that it is wrong—or selfish—to take children and family into account when dreaming big dreams.

Herself a mother of five, Birk tells students that the most concrete positive impact one can have on the world is through having children: “It’s worth it for you, for your family, and it’s worth it for the world. All major scientific and moral advances have come from human beings, and if you think you’re a good and moral person, you’re exactly the kind of person who should be having kids.”

To be sure, having more children can take a toll on one’s career—in most cases, the mother’s. And children are expensive. Estimates vary, but economists guess that children can cost parents anywhere from $200,000 to $1 million in expenses and lost income potential over a lifetime.

Yet despite the high upfront costs of having a child, proponents of larger families say that the long term benefits pay off over decades: in the long run, your children give much more to you than you give to them. Perhaps these sorts of calculations don’t even capture the fullness of it. In Birk’s words, “We all have the sense that to bring a child into the world is to touch infinity—is to touch G-d. You never have that chance in anything else you do.”

In The Case for Children, Weinstein addresses the limits of economic arguments against child rearing, even if he is rather skeptical that having children needs to cost as much as we think it does: “Let me play devil’s advocate: let’s agree that a baby does in fact cost you $1 million. Congratulations: you now have an asset worth $1 million. You’re a millionaire!” Weinstein makes the case for moving away from thinking of children as liabilities and instead seeing them as assets: “Yes, in purely material terms, children are expensive. Yet they’re also a priceless blessing and the best investment you can make in terms of your—and society’s—future.” What’s necessary, in other words, is to move away from the conception that children are burdens and move toward thinking of them as precious gifts.

Oftentimes a couple will agree, in principle, that raising children represents a wonderful opportunity, but this agreement itself can influence their decision-making. The value a modern couple places on having children can also lead some to overthink parenting and its attendant responsibilities, concluding that having fewer children means that they can invest more in each one. This is a difficult matter, heavily influenced of course by one’s context and conception of what is normal. And there are always factors like fertility, health and fortune that are beyond our control. There is no right “number,” and every family’s situation is unique and comes with particular considerations. But is it possible from time to time to subtly encourage, or even merely suggest, that a family expand its sense of what is possible and ideal for them?

That’s what Rabbi Yitzchak Shochet, the rabbi of the Mill Hill Synagogue in London, tries to do in his own dynamic community. His remarkably young congregation counts more than 1,800 members and enjoys the distinction of having the largest proportion of children under the age of twenty of any individual community in the U.K. (and likely, by extension, in Europe). Rabbi Schochet attributes this in part to the opportunities he senses for children in the community, with two Jewish primary schools within walking distance of the residential district and to the cohesive community spirit.

Here too, financial concerns likely impede family growth. And so may increasing anxiety about anti-Semitism in England and uncertainty surrounding Jewish life in Europe. Nevertheless, Rabbi Shochet believes that it’s possible to challenge congregants to reconsider some of their assumptions about family size, whether individually or from the pulpit: “I have often made the argument to many a couple that however many children they have decided upon, they should go for one more.”

It’s unrealistic and unfair to ask your average Western family to start repopulating their society in a fashion that would put them at odds with their surrounding culture. But to ask a family to consider expanding their sense of what is possible for them just a little bit may be something they would be grateful for in the long run. It’s not uncommon for women and men just past their childbearing years to regret not having had more children. It’s practically unheard of for adults to regret the birth of a child who is now a treasured part of their family.

For Rabbi Schochet, the challenges that stand in the way of having more children are real, and in many ways, children are “a harder sell than ever before.” Rather than getting mired in pragmatic arguments, he suggests that “the key is to bypass reason and appeal to the heart in the hope that people will appreciate that kids are the most prized possession of all.”

Goldman’s Why Civilizations Die, echoes this sentiment, recognizing the limits of purely rational arguments: “When children become a cost rather than an asset, prospective parents must identify with something beyond their own needs in order to sustain child rearing.” Goldman writes, “there is no answer to the question ‘Why have children?’” Or at least, this answer is not something that scientists, philosophers, or the general culture is going to provide.

Ultimately, while the Western world has a very real and documented problem with population decline, within our own communities, this question should not come down to numbers. It should come down to our values and perspectives. Making a case for children means taking a religiously influenced stance on how we define human beings more broadly: as individuals with infinite worth and infinite potential. Pragmatic arguments have their place, but there are limits to them. What is needed more than anything is a shift in sensibility. This shift involves understanding that children are assets and not liabilities, and it involves expanding one’s sense of how much it’s possible for a parent to give, and how much love a human heart can hold. You can embrace these shifts whether you have twelve children or no children, and the result will be a more vibrant future for all of us.

When Krasnianski’s ninth child was born, she looked at her newborn daughter and understood that her world was about to change. Her daughter had Down syndrome, and while emotionally she was bursting with love for her baby, intellectually it was hard not to feel like this was something of a disaster. She was reminded of a talk the Lubavitcher Rebbe gave when she was in high school. In a series of talks that focused on family, the Rebbe spoke about the obstacles, particularly financial ones, that keep people from having more children. He reminded his audience that each child born into the world creates a new “channel of blessing,” be it material or otherwise.

As time passed, and Krasnianski began to see the blessings that her daughter Bracha (aptly named “blessing”) brought to her own life, that of her family, and their community around them, she began to appreciate the wisdom of the idea that she had heard the Rebbe speak about decades earlier. It has not always been an easy road, but for Krasnianski and her family, welcoming this additional child opened up new vistas of joy and spiritual awareness that they might not have perceived earlier.

In the poem “The Possibilities of Language” the poet Yehoshua November describes the disparaging attitude toward children displayed by a distinguished poet he once met in a hotel lobby: “She was a great writer,” she said, “until she had children.” He contrasts this perspective with that of his own teacher:

A child is infinity,

my Rabbi said when we met

in the worn-down yeshiva coat room

After my wife had given birth.

A child is infinity, he repeated,

Without explaining.

Sarah Rindner teaches English literature at Lander College for Women in New York. Her writing on Jewish and literary topics has appeared in the Jewish Review of Books, Mosaic Magazine and other publications.

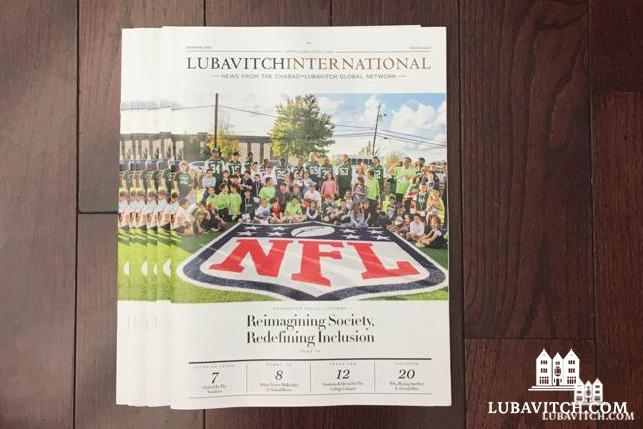

This article was featured in Lubavitch International, Summer 2019. To order your copy, visit www.lubavitch.com/subscription

Be the first to write a comment.