Your neck is adorned with strings of jewels

—Song of Songs 1:10

R. Abahu was expounding and the audience was dozing. He said, “Perhaps I am not stringing together the words of Torah properly. For Rabbi Levi said: There are those who know how to string together Torah passages but do not know how to pierce to the core of the issue, and there are those who know how to pierce but do not know how to string . . .” (Midrash, Shir HaShirim)

The High Holidays are times that touch the soul, a season meant for reflection and supplication, a time to assess where we have been in the past year and to set our direction for the year to come. These are called “Days of Awe” for good reasons; we feel the magnitude of what it means to be part of a vast creation in which the role of each individual is reviewed before the heavenly court.

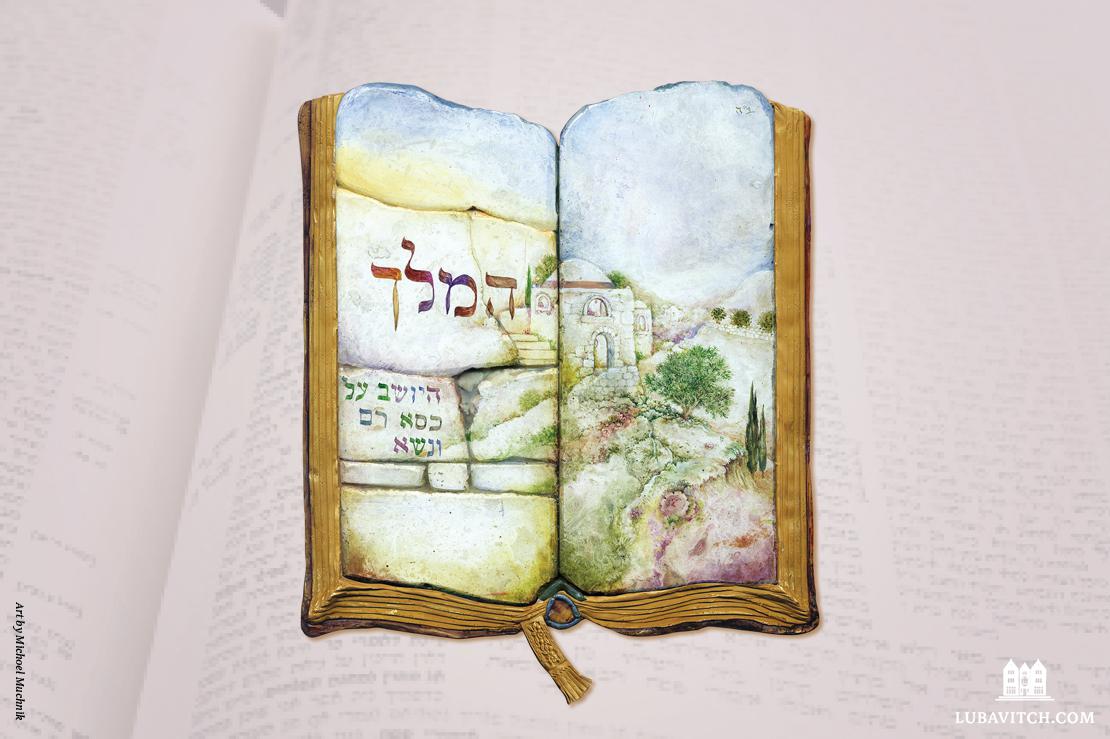

To address this on our own would be daunting. So sages and teachers arranged for us the text of the machzor, where the themes of the day are carefully strung and deftly arranged through our prayers. The text is beautiful, the themes on point. And yet, many of us may find ourselves, like Rabbi Abahu’s students, dozing through the service.

But where words fail us, the shofar comes forward. Many have the custom of blowing it during Elul, the month preceding Rosh Hashanah, as a way to rouse us to the holiday season. On Rosh Hashanah itself, it is the primary mitzvah of the day. And the shofar blast is also heard at the conclusion of Yom Kippur, marking a memorable end of the fast.

The tenor of the shofar sounds shifts over those forty days. In the month of Elul, it is like the first twittering of the birds in the morning, awakening us to the new season, reminding us of what is to come. On Rosh Hashanah, it is at turns a rallying call and a piercing cry, rousing us where words cannot. And in the final moments of Neilah, it captures the desperate desire to penetrate the heavens. Quite simply, it pierces our souls with its reverberations . . . it takes the pieces of our hearts and our lives and binds them with meaning.

Neilah means locking. It is perhaps only natural then, that as the sun goes down at the end of Yom Kippur, when the gates are about to be “locked,” we want to know that our prayers were heard, and that they will be answered. We wish, desperately, to be certain that the trials and tribulations of the past year are behind us. And perhaps our deepest desire in those final moments of Neilah is to know that we have not been “locked out”—that no matter what awaits us in the coming year, we are not alone.

Where words fail us, the shofar comes forward. It pierces our souls and the very heavens with the reverberations of its sound. It takes the pieces of our hearts and our lives and binds them with meaning.

Of that, we can be certain. The midrash, in Shir Hashirim Rabbah, speaks subversively to this feeling:

R. Elazar Hamodai said, “In the future, the celestial angels representing the nations will come to accuse the Jewish people before G-d, saying “Master of the Universe—the nations have worshiped idols, but the Jewish people have worshiped idols too; the nations acted promiscuously, but the Jewish people have acted promiscuously as well; the nations have shed blood, but the Jewish people have also shed blood. If the nations descend to hell for their actions, should the Jewish people not also descend to hell?”

G-d shall respond, saying, “If so, let all the nations descend with their G-d to Gehinnom, and I will descend there with the Jewish people…”

Rabbi Reuven said, “Were the matter not explicitly written, it would be (sacrilegious? no–) impossible to say . . . This is what King David meant when he wrote . . . ‘Though I walk in the valley overshadowed by death, I will not fear evil, for You are with me’ [Psalms 23:4].”

The Chasidic masters pick up on this theme. Although all of us face disappointment and disillusionment—sometimes with the world outside us, and sometimes within ourselves—the lost pearls of our soul are gathered and pierced in one moment of longing and loving. No matter how far we are, no matter the challenges that we may encounter, through it all, we are locked in together with our Beloved.

Nathan Law

Amazing