In Chaim Potok’s classic novel My Name Is Asher Lev, a young Chasidic boy tries to integrate his religious faith with his prodigious artistic talent. In school he scribbles on the margins of his sacred books. On weekends he takes clandestine trips to view Renaissance art at the Brooklyn Museum. Throughout the novel he grapples with the question: Is art something that brings us closer to G-d and to the Jewish people, or does it operate on another plane entirely?

Asher Lev is a member of the Ladover sect, a thinly disguised stand-in for Chabad-Lubavitch, and the beloved Ladover Rebbe gently explains that it makes no difference whether a man is a shoemaker or a lawyer or a painter; rather, “a life is measured by how it is lived for the sake of Heaven.” Yet, despite the Rebbe’s encouragement, ultimately Potok’s book insists that the chasm between the life of a Chasid and that of an artist is impossible to fully bridge.

The role of visual art in the religious Jewish worldview has always been somewhat tenuous. This may be rooted in the Torah itself: the second of the Ten Commandments prohibits the creation of graven images and the “likeness of any thing that is in the heavens above, that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.” But it may also be an accidental byproduct of history: the destruction of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem in all its aesthetic glory, the exclusion of Jews from artistic guilds, and the overwhelming dominance of Christian iconography in the history of Western art. While Jewish decorative arts abound—micrography, illuminated manuscripts, silver Judaica items—Jewish representation in the fine arts, at least prior to the modern era, is decidedly less pronounced. And while Jewish individuals have achieved prominence as modern artists, they tend toward secularism and individualism in both worldview and artistic language. We have yet to see a uniquely Jewish artistic idiom arise—that is, a path forward for an artist who wishes to tie him- or herself to a Jewish tradition in visual art.

In the twentieth century, however, two Jewish leaders articulated an important role for visual art in religious life.

Upon visiting the National Gallery of London, Rabbi Abraham Isaac HaKohen Kook, the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine, once famously reflected that Rembrandt was among the few “great men” privileged to perceive the spiritual reality of the universe: “The light in his paintings is that light which G-d created on Genesis day,” he wrote. Throughout his tenure he championed the work of Jewish artists and writers, and supported the founding of the Bezalel Art Academy in pre-state Israel.

In America, the Lubavitcher Rebbe strongly supported the development of a Jewish artistic culture in both theory and practice. He encouraged the opening of the Chassidic Art Institute in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, in 1977, urging the gallery owners to keep going even when the public showed little interest and offering them financial assistance out of his own pocket. In a 1962 letter to the cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, with whom he had a long correspondence, the Rebbe wrote that artistic talent is “the ability to transform to a certain extent the material into spiritual, even where the creation is in still life, and certainly where the artistic work has to do with living creatures and humans.” The Rebbe added that the highest form of art is when it is used “to advance ideas, especially reflecting Torah and mitzvahs.”

The potential of people to enhance and not only contaminate the world is a theme in Halberstadt’s art—it is the story of Judaism, and it is embodied in the artistic process itself.

Great art that elevates our religious conscience exists in one sphere, but the Rebbe’s point about the greatness of art which engages with Jewish ideas, “with Torah and mitzvahs,” occupies another. One is not likely to find this art in the National Gallery of London or the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but rather nestled well within the Jewish community, in small galleries or tucked-away home studios. These sorts of artists are not churned out by prestigious art schools. In fact, they probably have a conflicted relationship with them altogether. The Chasid-artist, by his or her nature, lives torn among various commitments—to faith, to family, to an artistic vision that may at times be difficult to fulfill in its purity. But rather than dilute one’s art, the Rebbe suggests that these allegiances actually make it greater.

Translating Torah Into Visual Terms

In a practical, postmodern world, the conflicts described in Potok’s 1972 novel may feel like relics of another era. But the Asher Lev conundrum was recently revived by the hit Israeli television series Shtisel, centering on the life of Akiva Shtisel, a young Haredi man with immense artistic talent. Behind some of Akiva’s paintings that appear on the show is a real-life Israeli artist—an Orthodox illustrator named Menahem Halberstadt—with a wide-ranging oeuvre.

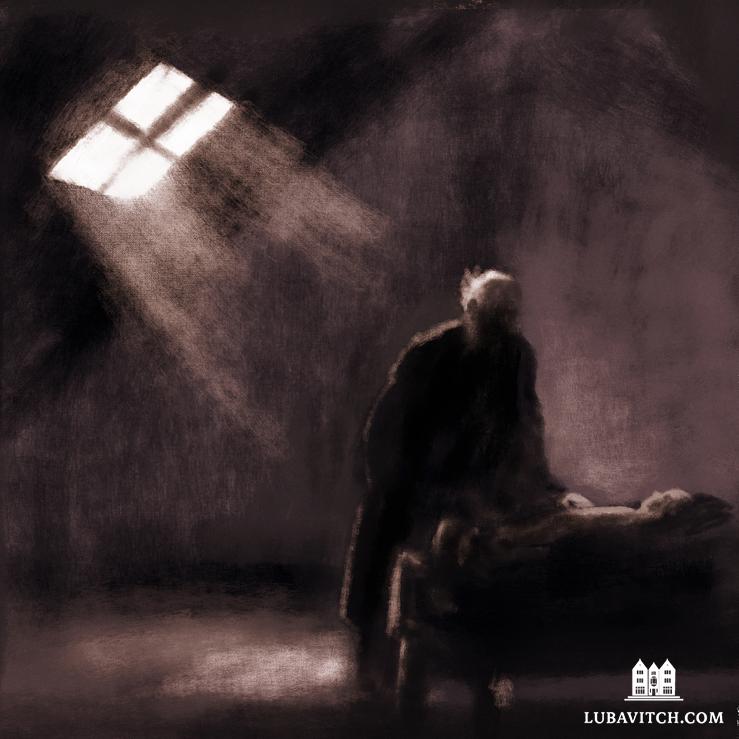

A father of five who lives and works in Tekoa, Israel, Halberstadt attempts to translate some of the Torah’s most profound narrative moments into visual terms. One image, a digital painting published in the Shabbat insert of the Hebrew newspaper Makor Rishon, depicts a scene from the book of Kings II: the prophet Elisha bends over the body of the son of the Shunamite woman, the child he once prophesied would be born to her. The light streaming in from the window on the upper left may not exactly be the light of Rembrandt, yet it too is a heavenly light. While nothing could be more dramatic than the miracle of bringing someone back to life, Halberstadt conveys a quiet and intimate scene. Prophet and child are cloaked in the soft, healing light of a G-d who both creates life and takes it away. In this work and others, Halberstadt is restrained and suggestive, capturing the complexity of the human response to revelation, without reducing or even attempting to depict the revelation itself.

It was only in Halberstadt’s mid-twenties that he began his formal art education, waking up early each morning before yeshiva to study art in Jerusalem with the prominent Moldavian-Israeli artist Leonid Balaklav. Balaklav initiated Halberstadt into the world of Western art. Eventually he studied illustration for a year at the prestigious Bezalel Academy. Halberstadt acknowledges that some tensions did arise during this time in his development as an artist. “I see, for example, among secular artists that I greatly admire, that their connection with art is a kind of deep covenant (he used the word brit), where art comes before everything,” he says. But a religious artist is one for whom “art is not the supreme value.”

The conflict between individualism and commitment to a greater cause is not the only challenge faced by a religious artist. Halberstadt explains, “One of the challenges for a contemporary Jewish artist is that we don’t have an artistic tradition. We once had the decorative art of the Beit HaMikdash and the Mishkan, but it’s been lost to us, and all we have left is the sefer Torah and the holy books.” Regarding his vision of Jewish religious art, he says: “We need to create something new, or to recover this artistic past. It’s essentially a journey into an unknown land.”

Halberstadt has engaged with this theme directly. Some of his paintings feature Biblical figures—Abraham, Moses, Hagar and Ishmael, and the Israelites—entering vast, barren landscapes. The contrast of small human figures dwarfed by sweeping natural panoramas is familiar from Western art: Thomas Cole and other members of the American Hudson River movement famously explored humans’ limited attempts to conquer and settle the natural world. But Halberstadt’s biblical paintings shift this equilibrium, as we see in these small individual figures the grandeur of their future potential. The natural world here is not the main story, but something that awaits transformation and redemption. The potential of people to enhance, and not only contaminate, the world is a theme in Halberstadt’s art—it is the story of Judaism, and it is embodied in the artistic process itself.

Giving Letters New Life

While Asher Lev’s specific brand of artistic and religious angst may not quite apply to Halberstadt sitting in his home studio in the Judean Hills, a more suitable heir might be found on his own home turf of Brooklyn. Hendel Futerfas is a Jewish artist and father of a young family who grew up in Crown Heights and is named after his great-great uncle Hendel Lieberman, a legendary Chabad artist who had a close relationship with the Lubavitcher Rebbe. Futerfas describes reading My Name Is Asher Lev as a child and being delighted by the many allusions to his family. (Aspects of Potok’s Asher Lev are arguably based on Lieberman, and other relatives of Futerfas’s, such as his grandfather Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, appear in the book in fictionalized form.) Yet while some parallels are there, Futerfas’s career as an artist would take another trajectory entirely, integrating his artistic passion and Chasidic spirituality in a fluid and organic manner, almost echoing the organic forms in which he works.

Futerfas, who now lives in Melbourne, Australia, describes a childhood surrounded by art, and Lieberman’s paintings in particular. His parents sensed an artistic inclination early and brought him for lessons with the prominent Chasidic folk artist Michoel Muchnik starting at nine years old. Muchnik kicked off a creative process for Futerfas that would include formal study at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology. On considering his status as a “religious artist,” Futerfas reflects: “My art always operated from a place that was in tune with spiritually. Whatever I’m philosophizing in my head, concepts of G-d that I’m trying to wrestle with, I’ve always tried to incorporate in my art.”

The Chasid-artist, by his or her nature, lives torn among various commitments—to faith, to family, to an artistic vision that may at times be difficult to fulfill in its purity.

Like Halberstadt, Futerfas works in a wide range of media. He has produced vividly realistic images of the Rebbe and other Jewish leaders, colorful abstract paintings that evoke specific mitzvahs and Jewish concepts, and more recently a series of unique sculptures that bend Australian timber into undulating forms. In much of his work, Futerfas displays a preoccupation with Hebrew letters, and this interest has expressed itself in his newest sculpture project, which involves carving out large-scale Hebrew letters and then casting them in metals like bronze and stainless steel. While in most cultures letters have meaning only in the context of words, in Judaism, Hebrew letters have inherent meaning and spiritual potential. The Kabbalah describes how G-d created the world with the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet; mystical teachings see the letters as the metaphorical building materials of the physical and spiritual worlds. In his sculptures, Futerfas seeks to imbue inanimate materials with some of this cosmic vitality. Though built out of heavy wood and metal, they suggest movement and dynamism, and even evoke humanesque forms. The idea, Futerfas explains, is to give the letters a bodily life (without actually being bodies).

In doing this, Futerfas indirectly engages with the prohibition of graven images, which rabbinic law sees as applying to sculptures of the human form. Here Futerfas proposes a new paradigm for Jewish sculpture that is based on a central component of Judaism—the written word.

Another Artistic Covenant

In considering the success with which both Halberstadt and Futerfas inhabit their religious and artistic identities, one wonders whether some of the intractable conflicts present in a book like My Name Is Asher Lev have been overstated. Or perhaps whether religious Jewish communities, in part due to the encouragement of certain visionary leaders, have moved toward transcending them. Growing up in Crown Heights, Futerfas was rarely discouraged from pursuing art as a vocation, and he is able to support his family through the sales of his artwork within the religious community and beyond. Halberstadt movingly describes the shell-shocked days following October 7 in Israel, when his neighbors and friends approached him and thanked him for creating art that brought to the surface emotions they had roiling within them. It’s true that sacrifices are made: The audience of a Chasid-artist is necessarily going to be limited. The choice to prioritize family life also necessitates many kinds of compromises. Yet the refusal of such an artist to cross religious red lines, to the extent they exist, does not make him an artistic “sellout.” Rather, it enables him to operate within a specific tradition, adding depth and meaning to its cultural tapestry.

At one point for the Lubavitcher Rebbe and Jacques Lipchitz, a real disagreement did arise. In 1960 Lipchitz was asked to donate some works for a new sculpture park that was being planned in the center of Jerusalem, a project that Lipchitz believed would contribute greatly to the flourishing of cultural life in Israel, and more broadly to the “emergence of Torah from Zion.” After reaching out to the Rebbe for his blessing, Lipchitz was taken aback by the vehemence of his response. The Rebbe felt that building a sculpture park in Jerusalem would be inconsistent with its nature as a holy city, especially knowing that many of the sculptures present (unlike those of Lipchitz) would transgress Biblical prohibitions. Certainly, the Rebbe valued Lipchitz as an artist— a sculpture gifted to him by Lipchitz remained among his possessions—yet for the Rebbe, the Torah is the source of holiness, and art that operates outside the bounds of Jewish law is unlikely to lead one to spiritual heights.

Such circumscription or censorship of great art on religious grounds is surely anathema to the Western mindset. Yet for the Chasid-artist it is a paradigm that enables an entire world of meaningful art and relationships. At a certain point in Potok’s novel, the Ladover Rebbe sends Asher Lev off to study with a famous Jewish artist named Jacob Kahn. Kahn, in fact, is loosely based on Lipchitz, although the real-life sculptor seemed to have much warmer attachments to traditional Judaism than his fictional stand-in. At one point, when considering the Talmudic statement that “all Jews are responsible one for the other,” Kahn turns to Lev rather harshly and says “Listen to me, Asher Lev. As an artist you are responsible to no one and to nothing, except to yourself and to the truth as you see it. Do you understand? An artist is responsible to his art. Anything else is propaganda. Anything else is what the Communists in Russia call art. I will teach you responsibility to art. Let your Ladover Hasidim teach you responsibility to Jews.”

There is something powerful about Kahn’s speech here in his call for the purity of art. Yet the speed with which Asher Lev gives up his responsibility to his family in subsequent pages is also disheartening—he displays certain paintings that humiliate his devout parents; he uses Christian iconography to depict his mother at a moment of great vulnerability, and places it on display. What’s remarkable about artists like Halberstadt and Futerfas, aside from their artistic talent, is how they choose another path. Perhaps there is a way in which commitments to family, faith, and the Jewish people may compromise the “purity” of art conceptualized as existing only for its own sake. But there’s another lens in which this purity is itself a compromise of the very values and commitments, the covenant that Halberstadt speaks about, which gives our life the sort of beauty and transcendent meaning that a Chasid-artist attempts to express through his work.

This article appears in the Fall/Winter 2024 issue of Lubavitch International, to subscribe to the magazine, click here.

Be the first to write a comment.