Wherefore I perceived that there is nothing better, than that a man should rejoice in his works; for that is his mission . . . (Ecclesiastes 3:22)

“The Rebbe created a culture,” a friend recently remarked in fascination. We were in synagogue on Shavuot, and young mothers had come pouring in with their children to hear the reading of the Ten Commandments. My friend recalled that this was not part of our childhood experience.

I almost forgot. In 1980, when we were just starting our own families, the Rebbe called on us to ensure that our children be present in shul during the Shavuot Torah reading, so that “the words of Torah will be engraved in the hearts and minds of the children.”

The Rebbe’s shluchim (emissaries) ran with the idea, organizing ice cream parties and other child-friendly events around the Torah reading schedule to induce kids to come to shul. From Brooklyn to Brisbane, an obscure holiday that many Jews had never even heard of soon became popular.

Myriad other ideas introduced by the Rebbe are today part of the culture he created. Just as he cleared the path for Jewish children to become dynamic players in the Jewish experience, he sparked a universal revival that brought Jews out of hiding, and Judaism out of the shadows.

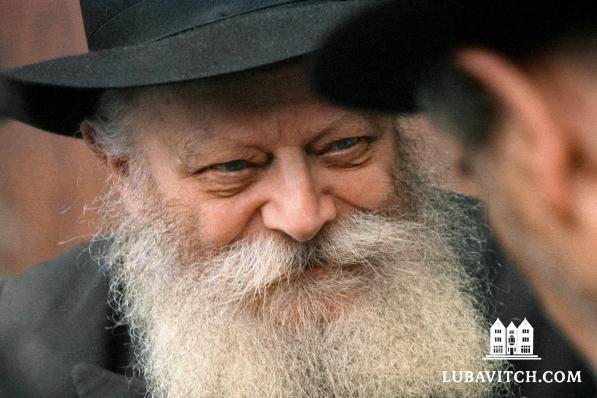

That we often forget the cultural shifts stimulated by the Rebbe is testament to how successfully and seamlessly they’ve been adopted. Now, on the 27th anniversary of his passing (this year it falls on June 13), we remind ourselves that what we take as givens were not always part of the landscape. And we are right to wonder, how did he do it? Or better, how did he get his shluchim to do it?

Reflections on the Rebbe usually elicit anecdotes about his all-embracing love and unconditional acceptance. This was so widely experienced, we needn’t belabor the point. But the work that his emissaries do indicate that love and acceptance, activating as they are, do not alone account for the transformation that the Rebbe triggered. There was more.

In his introductory discourse in 1951, when he finally agreed to succeed his father-in-law as leader of Chabad-Lubavitch, the Rebbe spoke of the difference between Chabad and other Chasidic schools. The latter invest their rebbes with full responsibility.

“We of Chabad, however, all have to do our own work alone, with all the 248 organs and 365 sinews of the body and with all the 248 organs and 365 sinews of the soul.” Transformation— the work of perfecting the world—said the Rebbe, ultimately depends on the efforts of the individual.

His inimitable talent for seeing the reflection of G-d’s image in the individual inspired not only the Rebbe’s love for each person, but also a confidence in his or her agency. He believed that each one of us is divinely endowed with transcendent potential, and he expected us to own the privilege and answer to the calling.

It is easier, of course, to stay within our safe spheres. So we speak mostly of the Rebbe’s love and acceptance. But that doesn’t convey the experience of the Rebbe honestly. We need only look at how he responded to people who sought his advice, to see that he always pushed the boundaries, relentlessly goading them out of their comfort zones.

To a woman recovering from cancer who wrote to the Rebbe that she is overwhelmed by sadness because of what she’d been through, he wrote, “You have neighbors who need you. Make time every day to visit them and help them.”

To someone who complained that he didn’t feel comfortable reaching out to other Jews, the Rebbe said, “Don’t make this about yourself. Go with the knowledge that you are riding on the shoulders of giants and your discomfort won’t get in the way.”

When a student began to say that the circumstances he finds himself in would dictate his decisions, the Rebbe interjected: “You don’t find yourself in circumstances. You create your circumstances.” How enlarging! The rabbinical student would later become the chief rabbi of the United Kingdom.

Today, we refer to the Rebbe’s responsa and his talks for guidance when grappling with practical, moral or spiritual dilemmas. Even as he advised people in the throes of great turmoil, deep suffering, or existential crisis, the Rebbe’s empathy was genuine, but never condescending. He took their pain personally, but he never coddled them in their helplessness.

On the Rebbe’s yahrzeit we visit his resting place and bask in the nostalgia of his love and embrace. Salve to the sorrows of this world, balm to our wounds, the memory nudges us forward, higher, to do, as the Rebbe said in his inaugural discourse, “the hard work of fulfilling a mission uniquely our own.”

Judy Keeler

I love the Rebbe. I share his English birthday and I was born the year he became Rebbe.