Most of the millions of people who cross the Brooklyn Bridge every year have seen the Ari Halberstam Memorial Ramp signs, but many may not know who Ari Halberstam was, or why Mayor Rudolph Guiliani installed those signs in 1995.

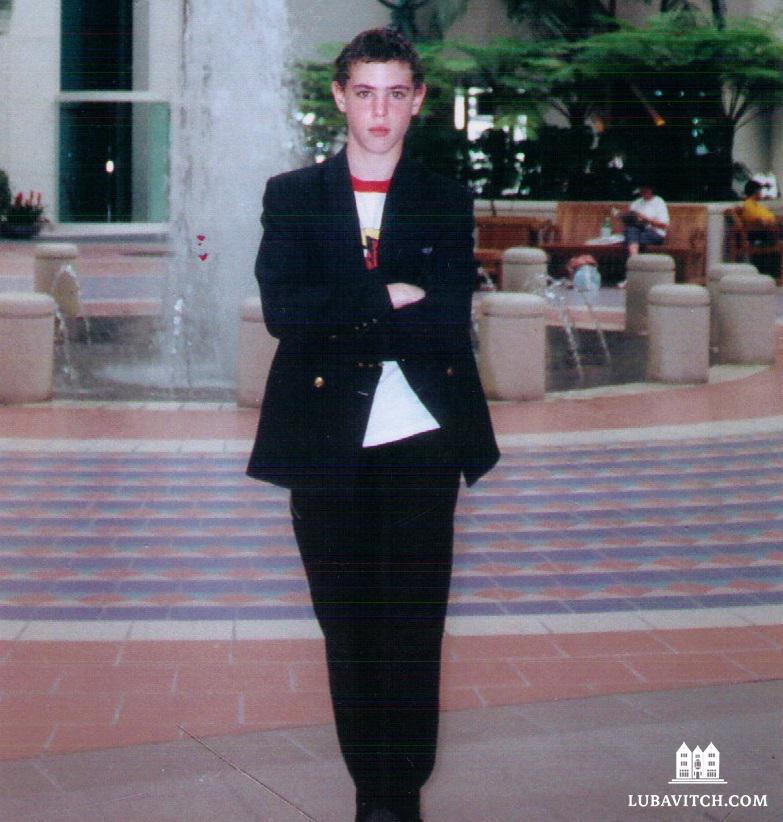

Twenty years ago, Ari was the 16 year-old yeshiva student who was shot in the head by a Muslim terrorist. Within the Jewish community, especially the Chabad community, Ari is well remembered not only because he was the one—out of a vanload of 15 students returning from a prayer vigil for the Lubavitcher Rebbe—who took the deadly bullet from a spray of gunfire, but because of the unusual relationship he had with the Rebbe.

Like thousands of others, Ari was following developments in the Rebbe’s health since his stroke two years earlier. But the condition of the spiritual leader who had captured the imagination and reverence of world Jewry was a more personal matter to the aspiring rabbinical student. Ari was the child who sat in his lap and played at his feet—the closest semblance of a grandson that the Rebbe would ever have.

To Ari’s mother, Devorah Halberstam, buried in the details of her son’s life and its untimely end is a story that is one part a failure by authorities to read the clues, and one part the mystery of a bond that has tied her son to the Rebbe in life and afterlife. Twenty years later, she continues to unpack lessons from Ari’s murder, keeping authorities on their toes, and seeking solace in the spiritual crevices of his life.

When they were little, Ari and his siblings often accompanied their father to his work at the Rebbe’s house. The Rebbe and the Rebbetzin doted over the Halberstam children. “Sometimes, the Rebbetzin would call me and ask me to send the children—who called her “Doda” [auntie]—over after school. That’s how close she felt to them.”

But they were especially fond of Ari, the eldest. As a three year old, he played often in the Rebbe’s house. On one of those occasions he saw the Rebbe coming in at the end of the day and ran gleefully towards him. The Rebbe scooped him up and kissed him on the forehead.

On the morning of March 1, 1994, Ari left his home at 5:30 joining a van of yeshiva students. The Rebbe was scheduled for cataract surgery that morning, and many of his Chasidim wanted to be at the Eye and Ear Infirmary in Manhattan where they would pray for him during his surgery. The night before, members of law enforcement had visited the Chabad-Lubavitch community with instructions that no cars follow the same route that the Rebbe’s would be taking. Presumably, they had received tips of an attempt on the Rebbe’s life, and security around him was tight.

One Woman’s Activism

1994 was well before the age of terrorism as we know it. The first World Trade Center bombing happened a year earlier, but it wasn’t until 9/11 that terrorism surfaced as the threat of the 21st century. Yet Devorah refused to accept police reports that her son’s murder was a crime of road rage. Driven by inconsolable grief, a keen sense that something major had been overlooked, and a burning need to see justice done, she launched into a solitary grassroots campaign speaking truth to power at every level of government.

“It was so clear to me that this was terrorism,” she says. But while the pieces of the puzzle fell into place rather quickly for her, it would take many years, a good measure of chutzpah and relentless activism to get others to see what she saw: a terrorist conspiracy to target the Lubavitcher Rebbe in retaliation for the Baruch Goldstein massacre in Hebron a week earlier.

Over the years, Devorah worked closely with authorities, showing them how she connected the dots that they apparently missed. George Venizelos, FBI Assistant Director In Charge of the New York Field Office, has worked with Devorah: “She’s done an incredible job raising awareness of terrorism that affected her personally and the community that she lives in, so that no one experiences what she did.

“She has a close relationship with the FBI, and speaks to new agents and helps keep them focused on the effects of terrorism.”

In late 2000, six years after Devorah began her activism and shortly before 9/11, the FBI reclassified the case of Ari Halberstam as a terror crime. Although the murderer would not be retried because he had already received a sentence that would put him behind bars for life, Devorah’s work would prove significant to the Jewish community and beyond.

Michael Miller, Executive Vice President and CEO of the Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC) in New York City, cooperated with Devorah from the very beginning. “Devorah has, in great part, ensured the safety of the Jewish community, not only in New York, but beyond. She just doesn’t want to see anyone suffer what she suffered,” he said.

As a result of her work, Miller told lubavitch.com, “authorities have become much more alert and sensitive to the realities of our vulnerability, providing funding to non-profit organizations to bolster security, none of which would be a reality had it not been for Devorah’s heroic activities.”

Rashid Baz, who is serving 141 years, trailed the Rebbe’s car until he got to the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. But authorities closed the Tunnel after the Rebbe’s car passed. So Baz turned his vehicle around and made his way up the Brooklyn Bridge ramp. Spotting the yeshiva students as they were heading up to the BB, he unloaded his cache of ammunition into their van, killing Ari and wounding three other students.

A Rare Bond

In her kitchen, Devorah has a black and white photo mosaic of Ari. As she looks at her son’s face, she speaks of the love he had for the Rebbe and the Rebbetzin, and how they reciprocated. When Ari was away at summer camp, he would get calls and care packages from the Rebbetzin. When he was older, he began going to farbrengens, joining the thousands who would pass by the Rebbe when he distributed kos shel bracha (blessings). The following morning, the Rebbetzin would share the regards she got from her husband about Ari.

“The Rebbe would comment on Ari’s mood, his appearance and other such things, which his wife would then share with Ari’s father,” Devorah recalls.

Then there are curious details. On the Jewish calendar, the month of Adar is supposed to be the most joyous month of the year. But for Devorah, Adar is an especially difficult month; it was in Adar that Ari was shot and five days later, in Adar, that he died of his injuries. The Lubavitcher Rebbe suffered a stroke twice, two years apart, both times in the month of Adar.

It was in Adar, the first Purim after the Rebbe’s wife had passed away, following the megillah reading in 770, that the Rebbe turned to Ari’s father and quoted the last line of the megillah, hinting that the Rebbetzin’s memory will be carried on by the Halberstam children.

“I will never understand what happened here—spiritually speaking. But I know there’s more than meets the eye,” says Devorah, whose son’s resting place, she points out, is only a few feet away from the Rebbe’s.

Understanding Instead of Hate

Shortly after Ari was murdered, Devorah was asked to become involved in the creation of the Jewish Children’s Museum. Desperate for a way to educate people, especially children, about Judaism, and the Jewish life that Ari lived and loved, Devorah raised millions to establish the Museum. “This would be open to children of all faiths, ethnicities, denominations, who can come here to learn about our culture, our history, our traditions.

“If people learn and understand, prejudices fall away. And what better way to do this—to prevent another generation of people growing up with hatred—than by teaching the children?”

In Jewish tradition, someone who is killed because they are Jewish is accorded the status of a martyr. “Ari was only 16 when he was killed. He lived a simple, pure life, centered around home, yeshiva, shul and the Rebbe. We lived on the corner of Eastern Parkway down the block from 770. Tefillin was very important to Ari—he was very dedicated to sharing the mitzvah with others. “

When Devorah received Ari’s belongings, his tefillin were unraveled. He had just taken them off as the van was leaving the hospital, so he didn’t have a chance to roll them up. It was the last thing Ari did in his life—the mitzvah of tefillin.

“To me, this is what my son lived and died for—his Jewish identity.”

Joseph Paul Cimino

G-D Bless you and your family.

The world is such a blessing yet such heart wrenching things happen with terrorists so horribly hurting family members.

Thank you for sharing this.

Saul Asnis

I was on the bridge not too far behind the van and got Outland walked by them still bloody but I never knew it wasn’t considered a terrorist attack. I was there about 30 seconds afterwards and I had no doubt from moment one it was a terrorist attack