Why would anyone choose to send their child to a yeshiva? As traditional Jewish schooling has recently come under fierce attack, this is one question that is rarely asked. Missing entirely from the discussion is an examination of what the yeshiva offers. As a parent of young children, it is a question I cannot afford to ignore.

Sitting somewhere on my children’s bookshelf is a clever picture book with an important point. It’s titled This Is How We Do It, and in thirty or so pages of charmingly rendered illustrations, the book showcases the lives of seven real-life children from around the world, from Peru to Uganda to Russia. Step by step, it proceeds through almost every part of a typical day: we find out where they live, meet their families, see what they wear to school, how they learn, what they eat. Ribaldo from Peru lives in a house built by his father in the Amazon rainforest and wears a “lion-buckle belt” to school; Kei of Japan wears indoor slippers in her classroom, studies “ethics” as a subject, and sleeps on a futon at night. In some ways, we discover, kids from Russia and Nigeria aren’t all that different; in other ways they are. And more crucially: We have our way of doing things, but there are other ways, too.

From time to time, in a desperate attempt to get my children to eat something different for a change, I’ll take the book down from the shelf, and wave it about. “Did you know they have miso soup and grilled cod for breakfast in Japan? And in India, paneer paratha with chutney?” I implore them, as they refuse to eat a tomato. Do I know what paneer paratha is? No, of course not. Still, I carry on undeterred, hoping that the point will get across. (It doesn’t.)

This book came to mind again not too long ago, and not just because I was trying to get the kids to help out with the vacuuming (like in Russia) or the laundry (India). Instead, I was thinking about some of the recent, and increasingly heated debate about yeshiva education.

In the classical sense, a yeshiva is an institution for the advanced study of Talmud and Jewish thought—the Jewish equivalent of a liberal arts college. However, the term is widely used outside the context of higher education to refer to a Jewish school, elementary or secondary, focused predominantly on religious studies.

Within this broad category of Torah-focused education, not all yeshivas are alike. Instruction might be in English or in Yiddish. Some will focus more on Talmud, others on Chasidic texts. In most cases, yeshivas include some level of general studies—subjects like language arts, math, and science. But the common denominator of all traditional yeshivas—indeed, what makes a school a yeshiva—is that the main focus is Torah study, traditional Jewish values, and the initiation into religious life.

But many may wonder why parents would choose a yeshiva for their children. How will such an education prepare children for life? Perhaps, I imagined, the debate could be elevated by the kind of pluralistic attitude gently sketched out in the pages of This Is How We Do It. The yeshiva differs from conventional schooling in some ways, but not in others. If the mindset espoused by the book might (one day) move my kids to tolerate the thought of fish for breakfast, maybe it could help make the case for a different, but equally legitimate, set of educational priorities.

There is another thought, a more reflexive one, that I have when I flip through the pages of This Is How How Do It. Encountering other educational alternatives makes us examine our own choices: Over the years, I have been fortunate enough to benefit from a yeshiva education myself. But it’s worth reflecting on what exactly it gave me. What has faded away, and what still remains? And now, blessed to make these same choices for my own children, I need to think hard about just what it is I hope to give them.

Not Just Knowledge

Professor Moshe Krakowski, the director of doctoral studies at Yeshiva University’s Azrieli Graduate School of Jewish Education, has been an essential voice in recent debates about religious education, putting out several deeply learned, long-form essays on the subject in the pages of the legacy Jewish magazine Commentary, the popular online heterodox publication Quillette, and elsewhere. In large part, as he told me over the phone, his work is one of translation—translating the values and priorities of yeshiva schooling into a language legible to the outside world.

For all its shortcomings and insularity, it is what I want for my children. I want to transmit to them a magnificent tradition, not only as an object of study or a family relic, but as a vital and life-giving experience. I want them to feel how it lives, and to know how beautiful it is when it breathes within them.

In this task, his own personal background no doubt plays a role. As a child, he studied at traditional religious yeshivas from across the gamut of contemporary Orthodoxy (including, a Yiddish-speaking Lubavitch cheder in Chicago) before going on to earn a Ph.D. at Northwestern University. Even within Yeshiva University, an institution that straddles the benches of the beit midrash and the groves of academe, Krakowski is something of an outsider, comfortable with questioning conventional wisdom about education.

Some of these shibboleths concern the most basic understanding of what schools are for and what they do. When asked what a school is, most people would suggest that it is a place for acquiring useful knowledge. But even this generalization, broad to the point of banality, does not get the whole picture.

Certainly schools transmit knowledge, and much of it is useful, but that can’t be the entire story. Krakowski points to numerous studies that have found that adults retain precious little of what they learn in school. The more relevant function performed by our schools, Professor Krakoswki suggests, lies in the various “non-cognitive skills” they impart to students—resilience, communication, discipline—and in preparing children for membership in society, or “socialization.” Yeshivas have their own way of doing that.

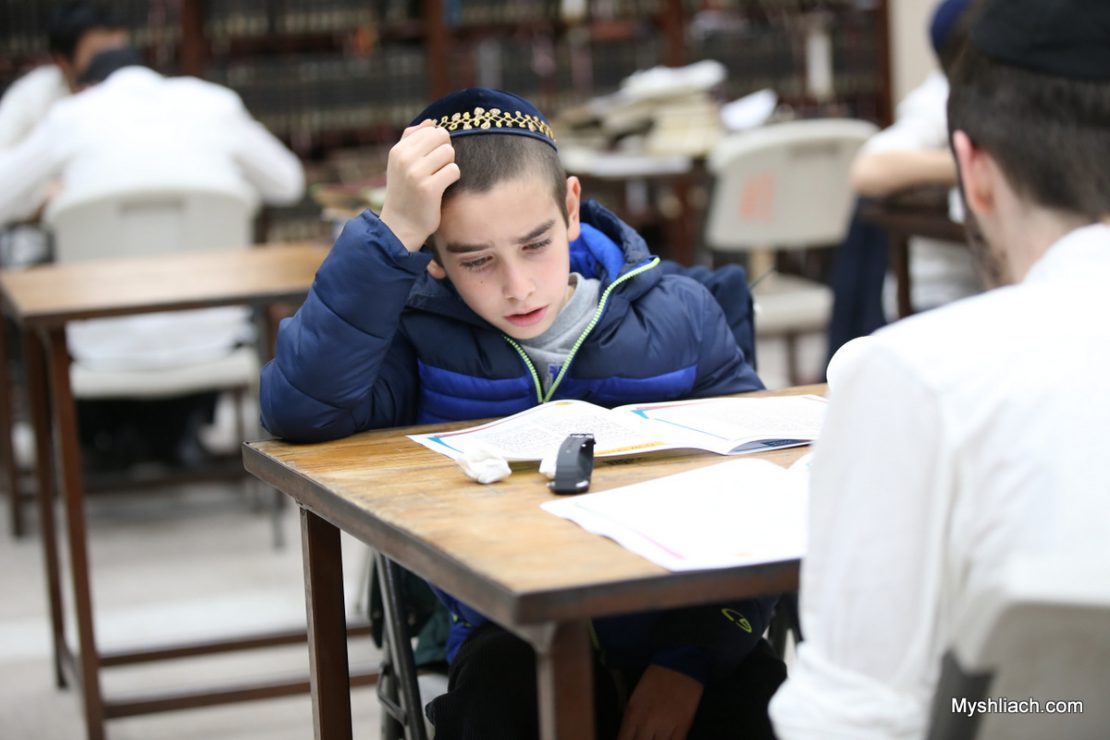

Baby in the Study Hall

In the classic Ethics of Our Fathers, the sage Yochanan ben Zakkai praises his disciple Yehoshua ben Chananya with an unusual turn of phrase: “Happy is the woman who gave birth to him.” Yochanan goes on to laud his other star students to the heavens, but nobody else’s parents come up. Now, we can only surmise that Yehoshua’s colleagues’ mothers were also very, very proud of their sons’ exceptional scholarly accomplishments. Why don’t they get a shout-out?

A passage in the Jerusalem Talmud helps us understand the unusual attention paid to Yehoshua’s mother. “I remember,” declares the venerable Dosa ben Hyrcanus, “that his mother brought his crib to the synagogue…”

The Italian commentator Ovadiah of Bartenura connects the dots: “It was she who made him a sage.” During her pregnancy, Yehoshua’s mother would go around to all the study halls in her city, soliciting blessings for her unborn child. Then, “from the day he was born, she did not take his crib out of the study hall, so that only the words of Torah would enter his ears.”

Thus the yeshiva emerges as so much more than just a place of learning. It represents the nexus of home, school, and communal life . . .

The metaphor of a small child, too young to study, too young to understand, absorbing the holy atmosphere of the study hall is a helpful illustration of Krakowski’s insight about the function of education. It suggests that Torah education is more than the mere transmission of knowledge. There is something else in the air of the study hall, in the sing-song of Talmud study, in the whiff of turning pages.

Of course, the study of Torah is the raison d’être of any yeshiva. It is a mitzvah, precious in its own right, not simply because of its utility later on in life. Basic competence in Hebrew, the ability to parse a mishnah or a page of Talmud, and some familiarity with Judaism’s great texts, are simply part of what it means to be a literate Jew.

There are also a range of second-order, indirect benefits to Torah study. The great value placed on scholarship means that high academic demands are made of the yeshiva student. Talmudic study demands facility in multiple languages, a high level of reading comprehension, and a capacity for analytical reasoning—all skills which are readily transferable to other fields. Students have to engage with and evaluate a kaleidoscope of opinions and views, swirling about on the same page of the Talmud, and then—especially for older students tackling a text together with a study partner, or chavruta—communicate their understanding to a classmate, who may have his own perspective on the matter. Just as important are the non-cognitive skills, like initiative, self-efficacy, perseverance, and grit, that get promoted in any kind of demanding, self-directed learning—no matter the subject matter.

But what really distinguishes the yeshiva is the context for all of this. Parents who send their children to a yeshiva desire an environment that respects and supports the beliefs and values of their home.

As a private school, a yeshiva’s only prerogative is to represent the families and communities it serves. Children learn about the holidays their families celebrate and the traditions they hold dear. On Fridays, they bring home some ideas from the weekly Torah reading to discuss with their family around the Shabbat table. Weekly parent-child learning programs are a regular feature of Jewish schools across the globe, designed to bolster the bond between parents and children. Indeed, in many religious communities, parents send their children to the same schools they attended. They, too, learned the very same passage of the Mishnah, or of Chumash, in their own time, perhaps with their parents before them, and on and on it goes.

The yeshiva’s curriculum is designed to support students in the development of their middot, or positive character traits, and the idea of duty towards each other and G-d. Professor Krakowski points out that much of the ethics instruction that takes place in such institutions is embedded in the regular curriculum. Talmudic law, for example, is filled with details about returning lost property or respecting the right to privacy. And more than just teaching virtues, a religious education aims to give the student a sense of purpose and place, an understanding of who they are and what life is all about.

Community

This takes us to the other major function of the religious school. The yeshiva plays a critical role by introducing its students into Jewish communal life, and in creating that community in the first place. In truth, this is hardly unique to religious schools. Every society seeks to reproduce itself, and to maintain the conditions for its survival, by raising up the next generation with the values and ideals it holds most dear—not least through its education system. Since the religious lifestyle is so distinct, and community is so central to it, this socialization process is that much more important.

The yeshiva is an integral part of the broader community and often constitutes a very real community in its own right. The schools will often step in to help students in need of assistance, even in areas unrelated to their studies or schooling. It’s not unusual for teachers and administrators to pitch in to help boys celebrating their bar mitzvahs with trappings their families might not otherwise afford, or to fundraise for more quotidian expenses.

Ultimately, this investment in communal life is itself critical to individual flourishing. Over the past few decades, the breakdown in families, religious organizations, and other forms of civic engagement has created an epidemic of loneliness and instability, and despair. For most people, being part of a community provides a crucial source of purpose and belonging. Robust communal life is an essential ingredient in raising healthy individuals.

Thus the yeshiva emerges as so much more than just a place of learning. It represents the nexus of home, school, and communal life, initiating the child into a world of mutual responsibility, community and religious duty.

Sustained Identity

Still, critics of yeshiva education argue that an immersive Torah education handicaps its graduates, leaving them incapable of ever venturing out of their bubble. But many products of the most rigorous yeshivas who have in fact made their way successfully through Ivy League colleges and universities put that to the lie. Many go into law, the sciences, business, politics, and other fields. It is true that some may need to work hard to fill gaps in their general studies, but even here the discipline of a serious yeshiva training will serve them well in this endeavor. The challenge is ensuring that, whatever their field, the air they breathed in the study halls of Torah over the years of their yeshiva education continues to animate their life-choices, informing their ethics, shaping their humanity, keeping them anchored and inspired as they go on to serve their respective communities.

Some also become spiritual leaders, rabbis, teachers of Torah. In the 1960s, the Lubavitcher Rebbe decided to send a group of students on a two-year mission to Melbourne, Australia, to serve the Jewish community there. As the story is told, a list of students thought to be well-suited to the task was chosen, all of them articulate, well-spoken, intelligent young men. They scrubbed up well and would be able to put a shiny, modern face on Chabad’s old-school Russian roots. But, when presented to the Rebbe for his approval, the list was vetoed. Instead of choosing the most sophisticated students of the yeshiva, the Rebbe hand-picked the least worldly, and the most studious, devout, devoted young men he could find. For some of them, English was a second, or even a third language.

Parents who send their children to a yeshiva desire an environment that respects and supports the beliefs and values of their home.

And yet, these boys’ devotion to their studies and to the culture of the yeshiva would make them best suited to present a compelling vision of Torah life to others. Their proverbial ten thousand hours of study within the walls of the yeshiva had given them a certain mastery, not only of the subject matter, but of the wholesome integration of Torah into their lives. Thus fortified, they were more capable of negotiating life outside the yeshiva.

Any parent will be familiar with this basic dynamic. For the first few years of life, we nurture our children, surround them with love in a protective little bubble, a cocoon from which they will eventually emerge into the world, confident and self-assured. Every parent decides what they wish to give their children, how long to keep them close, and when to send them on their way. This is how we do it, writ large, in the yeshiva.

And it’s what I hope to do for my own children.

The Judaism that I absorbed has given me a source of identity, a set of core values, a means of connection, a way of understanding the world, an ideal I can aspire towards, although never fully reach. Such connection to a faith and heritage is difficult to transmit in two-hour Talmud workshops, or even a semester of Jewish Studies. To find an organizing principle for your life, you need something larger than life, or at least some idea that transcends life itself. For me, it was the immersion in the yeshiva where I witnessed the commitment of people I respected, studied with teachers devoted to the ideas they taught, and was inspired by their example to put what I could into practice myself.

The yeshiva is a rare survivor in the twenty-first century, and I cannot take it for granted. For all its shortcomings and insularity, the traditions and beliefs it nurtures are what I hope to give to my children. I want to transmit to them a magnificent tradition, not only as an object of study or a family relic, but as a vital and life-giving experience. I want them to feel how it lives, and to know how beautiful it is when it breathes within them.

This article appeared in the Spring-Summer 2023 issue of the Lubavitch International magazine. To download the full magazine and to gain access to previous issues please click here.

Be the first to write a comment.