As is true of every close-knit cultural group that enjoys a history, traditions and habits particular and peculiar to it, conversations among Chabad Chasidim are typically peppered with terms that have meanings particular and peculiar to it.

For the eavesdropper, this sometimes results in a comical rendering of the conversation, leaving him or her mistaken or altogether clueless.

Tracing the Chasidic terms to its origins in early periods and places, we look at how the word evolved in the course of the travels and travails of the Jewish diaspora, to its current usage, opening a window to the rich lingo and cultural nuances of Chabad Chasidim.

Shtus D’kedusha

Kids can be very unpredictable. With no filter between what they think and what they say, thoughts that pop into their little heads tumble right out of their mouths a moment later. They’ll tell the man that he is fat or ask the woman in the wheelchair why her legs look funny. Maybe they’ll start doing a jig to the music playing in the local supermarket without a care about who is looking.

But their candor is also their saving grace. Unfiltered comments that might otherwise be hurtful, or spontaneous responses to stimuli that would be inappropriate for an adult, make us smile: how refreshing the naiveté and innocence of the loveable imps we are proud to call our own.

The Hebrew word shtus represents this switch-hitting sense of candor and brazenness. When adapted for the right purposes, it puts you ahead of the crowd and empowers you to do what others wish they could but fear they cannot. And if it’s adapted for nefarious purposes, then you end up with the adult version of children but with none of the redeeming parts.

But shtus isn’t limited to the freedom to say what you think. More broadly, it’s the freedom to buck social norms and expectations, to think what you want, to say what you want, to do what you want. Much of our daily behavior is shaped by what we feel is expected of us, by what is simply “done” and “not done.” Those expectations form normative behavior, and any deviation is called shtus (and indeed, that is the most literal meaning of the word).

Deviant behavior is almost always equated with improper behavior, much like abnormal is invariably used to describe something undesirable. But deviation from the norm can also be what enables us to achieve greater and better things. Doing things differently than everyone else is largely responsible for the success of every great inventor, artist and thinker.

This noble kind of shtus we call shtus d’kedusha.

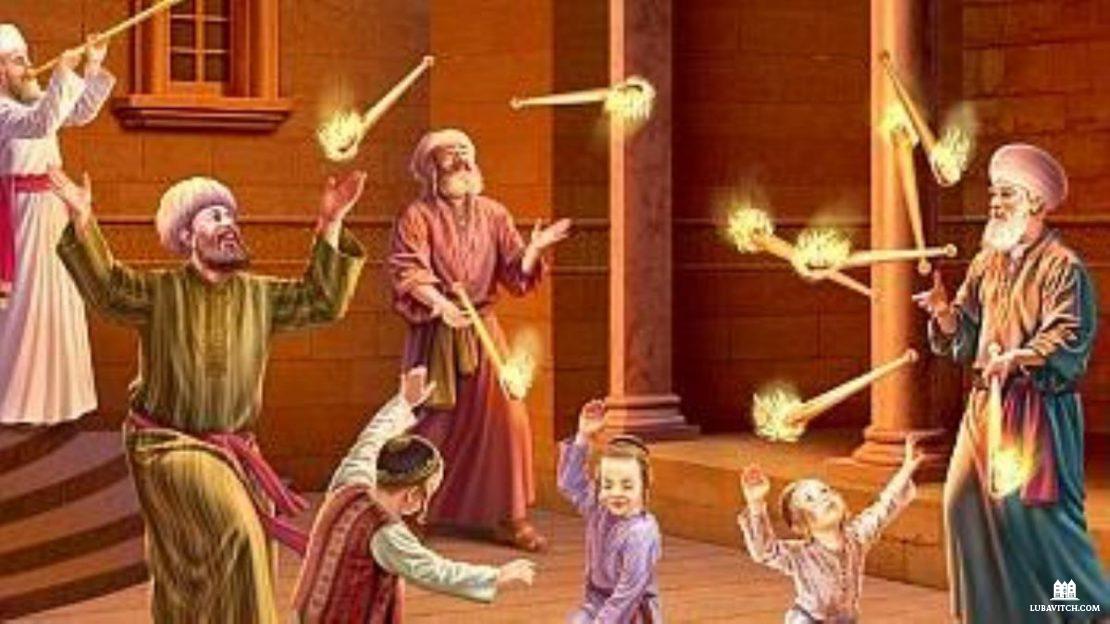

The fine line between shtus d’kedusha and reckless abandon (or even anarchy) isn’t always easy to find. When the Talmudic Sage, Rav Shmuel bar Rav Yitzchak took to the dancefloor at a wedding juggling three willow branches as he danced in front of the bride, his colleagues were aghast. “He is embarrassing us!” they said, shamed by the breach of propriety and protocol as he fulfilled the mitzvah of rejoicing “before a bride.”

But they were wrong. When Rav Shmuel died, a pillar of fire descended from heaven to escort this holy man on his final journey. By now, the Sages knew why. “His shtus helped him,” they said in awe. His unconventional outburst of joy was in fact the mark of a man whose behavior was constrained by nothing and no one but G-d.

Such has always been the Jewish way. When the Holy Ark finally returned to Jewish hands from enemy captivity, King David was “hopping and dancing before the L-rd.” Michal, his wife, looked with revulsion at this display, out of character for the royal king, but David was not ashamed. He loved G-d with unrestrained passion, not calculated reason.

Shtus d’kedusha—the holy unorthodoxy—is the bunker-buster bomb in a chasid’s arsenal. Sometimes, things can be done the usual way. Fill out the forms in triplicate, wait in line, submit them. Put knives on the left, forks on the right. Ironically, though, the G-d-human dynamic often defies convention, strays from the narrative. Our relationship with the Divine is an unusual relationship, so things can’t be done in the usual way. It is based not on what we think and what we think we should think, but on unfiltered love, unbounded joy.

Sometimes, like Rav Shmuel and King David and like the innocent kids we once were, we’ve got to dance like nobody’s watching.

Be the first to write a comment.