Tamim

[ta-meem]

noun: whole, pure, innocent

In Warsaw in the 1930s, just before the war silenced the sounds of Jewish learning, a yeshivah published a journal titled HaTamim. The title borrowed from the name of the Chabad-Lubavitch yeshivah, Tomchei Temimim. The yeshivah was founded in Lubavitch, Belarus back in 1897, but moved to Poland when the Rebbe relocated there in the 1930s, never to return. HaTamim was an extraordinary publication, combining high-brow expositions of Torah thought with rich descriptions of Chasidic life.

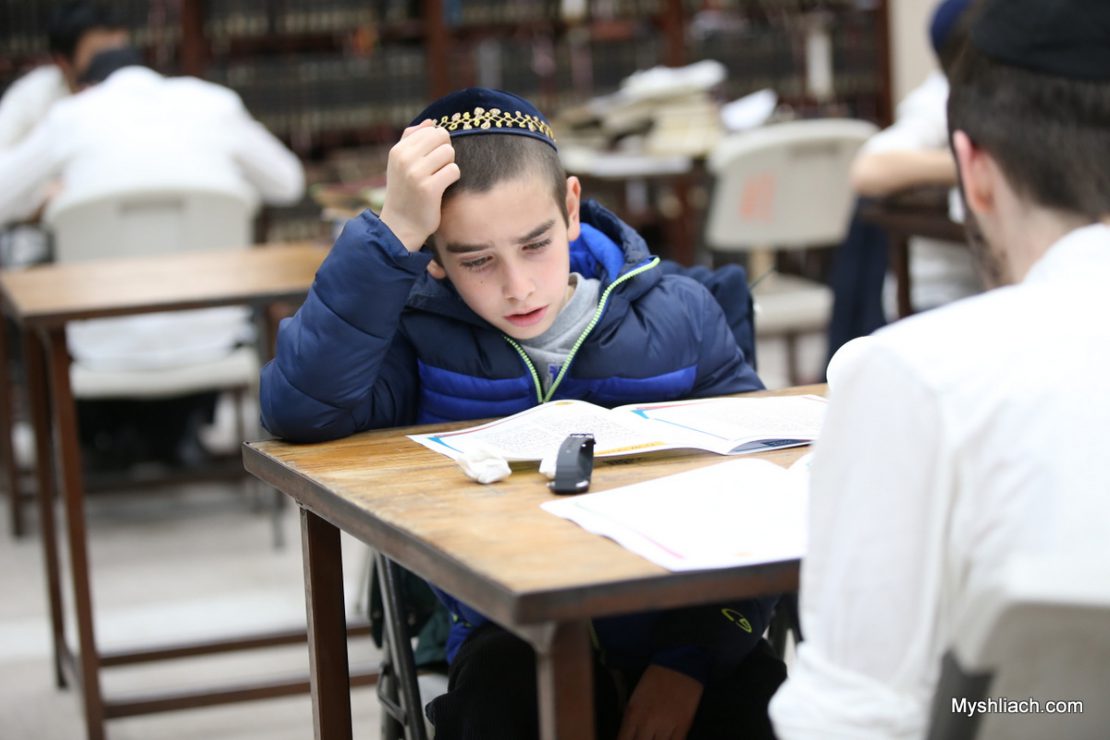

The journal had a short run, just the eight volumes, but its few issues are still cited and quoted today. But what never died was the title it took for itself: HaTamim (lit: the innocent one). Every Chabad yeshivah student today, no matter where on the globe he sets down his Talmud, exults in the title HaTamim, a proud member of the worldwide network of Tomchei Temimim yeshivahs.

But just how did this term become a byword for “Chabad yeshivah student,” the yeshivah equivalent of the lawyer’s “esquire?” What hope was there in the hearts of Chasidim of years gone by when they aspired to temimut, when they declared it better to be a tamim from the simple folk in the town of Nevel than an intellectual from the sophisticated city of Kremenchuk?

The word tamim is not a recent addition to the Jewish vocabulary. We are told in Deuteronomy that we are to “Be tamim with Hashem your G-d.” Tamim is variously translated as innocent, blameless, and wholehearted. Leaning towards that last translation, the foremost Torah commentator, Rashi, understands the verse to be a directive that mankind needs to hear more than ever: Do not be complicated, do not overthink, do not pretend to be what you are not. Be authentic and wholesome.

Since its Biblical appearance, the word tamim seems to have developed along two lines—lines that appear to run separately but which cross eventually.

The first line sees a tamim as a wholesome person, a model of integrity and honesty. Ernstkeit, the Yiddish word for temimut, is earnestness, a “sincere conviction,” and is quite similar to the English equivalent. We see here a shift in temimut’s meaning, from simplicity to sincerity. This sincerity is described as being the same person on the outside as you are on the inside. The very first sentence in the Baal Shem Tov’s classic manual of Chasidic living is: be a tamim in the way you serve G-d. Be sincere, be earnest. A word that comes up a lot is “artless,” meaning without guile or deception.

Who wouldn’t want to be a tamim? And how presumptuous of Chabad students to call themselves such!

But elsewhere in Chassidic literature, temimut has a pejorative hue. Here, tamim means simple in the simple-minded sense. Words like naivete, unsophisticated and gullible come to mind. Not that this is all bad. The Jew wishes he could believe in G-d with the unquestioning simplicity of the tamim; even the scholar aspires to the “prost [Yiddish for simple] temimut” of the simple Jew. “Prost” is Yiddish for common, vulgar. The tamim here is not a model of integrity, but a plebeian.

The two meanings of temimut are fused by the fifth Rebbe in his treatise, B’sha’ah Shehikdimu 5752. Across five pages of complex analysis, Rabbi Shalom DovBer paints a tamim as someone who is unflappable. He does not sway with the winds of change, nor bend to meet the expectations of others. He is a simple and straightforward person. What you see is what you get. He does not think too much, not because he is anti-intellectual, but because not for him is intellectual posturing with no purpose. What emerges is a picture of a person who is a tamim in both senses of the word. He is honest because he is transparent, with no veneer obscuring the truth. He is earnestly committed to his religion because he is not cynical or a second-guesser. He lives comfortably in the moment because he does not obsess about the past or worry for the future.

So the yeshivah student who unabashedly calls himself a tamim is saying two things, a backhanded compliment of sorts. I am uncomplicated and simple. Sorry, what you see is all that there is to me. Then there is the underlying aspirational statement: Because I am a tamim, I hope to be perfect, to be wholesome, to be a tamim today in the Western world like a tamim in 1897 Belarus or 1930s Warsaw.

Sources:1

B’sha’a She’hkdimu 5772 chapter 82.

Hayom Yom 5 Tevet; 3 adarII; 24 Iyar; 4 Tishrei; 14 kislev.

Be the first to write a comment.