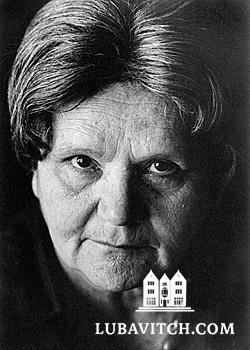

Among the poets in Israel’s literary circles, many quietly remembered Zelda Schneurson Mishkovsky on Tuesday (April 18) 27 Nissan. That Zelda, as she was simply called, died (in 1984) on the same day designated by the state of Israel as Holocaust Remembrance day, is in itself poetic; her poetry, for which she received the Bialik and Brenner Prizes in literature, speaks of death and darkness but also of renewal and transcendence.

Born in Ukraine in 1914, Zelda was the daughter Rabbi Sholom Shlomo and Rachel Schneurson. Her father was a brother of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, father of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, making Zelda first cousins with the Rebbe.

Zelda’s mother Rachel, was the daughter of a distinguished Chasid, Rabbi Dovid Tzvi Chen, who also descended from a long line of Chabad rabbis. In 1928, she immigrated with her family to Israel. Her father died shortly afterwards. In 1950, at age 36, she married Chayim Aryeh Mishkovsky.

Zelda’s students, translators and critics of her work discerned influences of her Chasidic background in her poetry. Indeed, one reviewer described her work as “a poetic expression of the tenets of Chabad, to which the poet was linked by family ties and spiritual leanings.”

Her poems, all in Hebrew and now widely translated in numerous languages, are filtered through a uniquely Chabad spiritual perspective that manages to startle readers—no matter their orientation. Contemplative as they are, they shatter fixed ideas yet find their footing at the kitchen table, making her—poet, woman, Chasidic Jew–an anomaly both within and outside of the literary world.

In her introduction to The Spectacular Difference (HUC PRESS), Marcia Falk, author and translator of Zelda’s poems recalls her first visit to the author’s Jerusalem home in the 1970s:

“I showed up at her doorstep in a knee-length skirt and a sleeveless blouse, a kerchief on my head. I had debated with myself about the skirt and blouse, knowing that the very religious do not approve of women revealing bare arms or legs; but the heat was oppressive that day and I had heard that Zelda was tolerant by nature. I didn’t give a thought about the kerchief, which looked, I later realized like the traditional tikhl worn by some Orthodox married women to cover their hair in public. I had worn it only as protection from the beating sun.

When Zelda opened her door to me, a bemused smile spread across her face. “You have a secular body,” she commented wryly, “but a religious head.” Her poems had not prepared me for her sense of humor. . . Little about Zelda turned out to be predictable. In that first visit I found her to be soft spoken, unassuming and even shy. But more than anything else, she was utterly original. I’d never heard anyone speak quite they way she did, and I was almost in awe of her for this . . .”

Amos Oz, Zelda’s student in second grade, recalled his teacher fondly in one of his recent books:

“Teacher Zelda also revealed a Hebrew language to me that I had never encountered before … a strange, anarchic Hebrew, the Hebrew of stories of saints, Hasidic tales, folk sayings, Hebrew leavened with Yiddish . . . But what vitality those tales had! … As though the writer had dipped the pen in wine: the words reeled and staggered in your mouth.”

Imagery and concepts from Jewish traditional and mystical sources abound in Zelda’s work, prompting readers to linger over her lyrical allusions to the infinite, the supernal, the otherworldly, as in this excerpt from A Sabbath Candle, translated by Varda Koch Ocker:

The candle’s sparks are palaces,

and in the midst of the palaces

mothers sing to the heavens

to endless generations.

And she wanders in their midst

toward God, with a barefoot baby

and with the murdered.

Hurrah!

The soft of heart comes in dance

in the golden Holy of Holies, inside a spark.

In one poem, named My Mother’s Room Was Lit, Zelda mentions the distinguished Chabad scholar, Rabbi Shlomo Yosef Zevin, who was editor-in-chief of the Talmudic Encyclopedia and a prolific author of many works, among them the classic Sippurei Chasidim.

And on the table, through the tales of the righteous, the golden

tales,

(that Rabbi Zevin gathered, collected),

a mountain breeze leafs slowly slowly,

mixing snowy landscapes with an arid landscape.

My mother is praying–on her head, silken checkers.

An only child, and childless herself, Zelda was broken by her husband’s death, and would continue to grieve for him for the rest of her life. She kept up a long correspondence with her cousin, the Lubavitcher Rebbe. Some of his letters to her have been published in various volumes of his Igrot Kodesh. Though her letters to the Rebbe remain unpublished, it is possible to infer some of what she must have written by his responses to her.

In one particular letter to Zelda following the death of her husband, in the summer of 1970, the discussion turns to coping with loss, the ascent of the soul and the imperative upon the survivors for life. The Rebbe urges his cousin not to become resigned to loneliness, and insists that the experience of the death of a loved one should rather stir a desire to live more intensely in a social environment.

Perhaps responding to one of her thoughts on the metaphysical, the Rebbe rejects the notion that physical illness affects the soul and its eternity:

“The change [in death] is only in terms of the connection between the soul and the body which restricts the soul, and when that association ends [with death] so do the constraints upon the soul, and the positive actions [in this world, by survivors of the deceased] are immediately known to the soul, as it is no longer confined.”

The Rebbe addressed his letters “To my cousin Shaina Zelda,” and concludes this one with a postscript:

“Obviously, I hope you will let me know how you are faring, especially with respect to your finances, and I trust that you will tell me things as they are—being that we are family, and especially as only very few remain among our surviving relatives.”

Appreciating her artistic achievements which no doubt derived largely from her identity with darkness, the Rebbe was nevertheless was pained by her angst, and often implored his cousin to turn her focus to the brighter side of life. In one letter, dated 1974, he chides her good naturedly, saying, “From the spirit of your letters, I get the impression that though I keep writing you to take a more joyful perspective . . . my words have made no mark . . . But I will persist, and repeat myself even 100 times, and you will forgive me . . .”

Maybe, the Rebbe’s words did leave their mark on his cousin’s poetry. That same year, Zelda published this poem—one of the few in her volume, Be Not Far (in the collection translated by Marcia Falk) that ends on a brighter note:

Enchanted Bird

When the feeble body

is about to fall

and reveals its fear of death

to the soul

the lowly tree of routine,

devoured by dust,

suddenly sprouts green leaves.

For out of the scent of Nothingness—

the tree blossoms—

glorious, beautiful.

and in its crown—

an enchanted bird.

Eleanor Bedar

On erev Yom Kippur, I am first hearing about Zelda Schneerson M. since her poem “Each of Us Has a Name” is included in my High Holy Day prayer book.Wondering if she was in any was related to THE Rabbi Schneerson, I did some research. After reading some articles and tearing up a bit, I determined that I will find a book or two of hers and very much look forward to enjoying her poetry.