As is true of every close-knit cultural group that enjoys a history, traditions and habits particular and peculiar to it, conversations among Chabad Chasidim are typically peppered with terms that have meanings particular and peculiar to it.

For the eavesdropper, this sometimes results in a comical rendering of the conversation, leaving him or her mistaken or altogether clueless.

Tracing the Chasidic terms to its origins in early periods and places, we look at how the word evolved in the course of the travels and travails of the Jewish diaspora, to its current usage, opening a window to the rich lingo and cultural nuances of Chabad Chasidim.

Farbrengen [n.far-breng-in; v.far-breng]

Faint echoes of German can be heard in Yiddish. Translators and lexicographers struggling to capture the meaning of a Yiddish word can sometimes amplify those sounds until a rich and nuanced definition resonates from the German origins.

Farbrengen, one of the most treasured words in the Chabad vernacular but usually mistranslated as “gathering,” is a fine example of a Yiddish word whose loan from German was seamless and complete. Verbringen means to spend or pass time; for example, “Sie verbringen im Glück ihre Tage” (a random sentence I plucked from Die Jüdische Litteratur) means “they spend their days in happiness.” And that’s what a farbrengen is—spending time with each other. The other synonym for farbrengen that bubbled up from the Yiddish-German brew was “pastime,” and that too is accurate. If baseball is the American pastime, a farbrengen is the Chabad one.

The life of a Chasid can be a lonely one; the farbrengen reassures him he is not alone. The Chasid wishes to lead a life of piety, but it seems no one told wider society about this arrangement, and so arrayed against him are the glittering and gross temptations of a world so inhospitable to his lofty dreams. In 2016, he struggles to lead a lifestyle that others scoff as belonging to 1716. At the same time, his household bills, his health concerns and his relationship worries are all very much of the present. And thus life grinds on. He is desperate to crush a creeping sense of ennui, to flush out his lethargy and fears with soul-shaking jolts of energy, to again feel alive and not alone.

Through this fog cuts the words of the prophet Isaiah: Each one shall aid his fellow, and to his brother he shall say, “Strengthen yourself.” This is the siren call of the farbrengen. Gather together, men of the brotherhood. Sit together in peace, in harmony, in fraternity. Share your burdens. Cry with your fellow in his pain, laugh with him in his joy. Critique each other with love; urge one another to be a better person tomorrow than you are today. Strengthen yourself, and strengthen others. In a crude sense, a farbrengen is Chabad’s answer to the bonding activities of Greek fraternities (both known by their 3-letter names and with hundreds of international chapters), a time for its members to support each other and rededicate themselves to the movement’s goals.

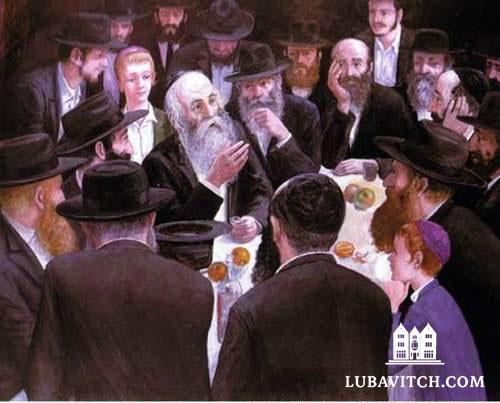

Practically, a farbrengen will most likely look like this. A group of men or a group of women will be sitting around a table, exchanging anecdotes, Torah thoughts, experiences and whatever is on their mind. It will be a relaxed atmosphere, with no rigid schedule, perhaps with some snacks and drinks. The group will periodically break out into Chasidic song, mulling over what they’ve just discussed as they hum the wordless melodies. Depending on how formal a farbrengen it is, there may be someone of Chasidic stature who leads the bulk of the discussion, dishing up nuggets of Chasidic inspiration in the form of tales from yesteryear or insights from the literature. It will almost always be nighttime, and for those few hours, a certain magic takes hold of the room as reality is suspended. The outside world disappears, and the group is no longer in New York and London. They have been transported to the farbrengens of old in the deep winter of Moscow and Lubavitch, the worries of today a world away.

But a farbrengen is no Woodstock-meet-Bialystock love-in, the strum of a guitar simply replaced by the strains of a niggun. The brotherly love fostered by a farbrengen is to be the fertile soil from which Chasidim grow their love for G-d. The word “brotherly” is apropos; the love that flourishes between Jews derives from the fact that they are children of their divine Father. And so the farbrengen is an important vehicle for religious growth and character development; much of the discussion will focus on where and how those present can implement change in their religious life. Where have we grown weak in our observance? How can we become better people? What attitudes need fixing? To achieve this, a farbrengen can occasionally be the scene of some of the rawest personal criticisms. But like a surgeon who wields a scalpel with utmost care, any criticism is motivated by deep concern and is received in the same spirit. It is this self-improvement dimension of farbrengens that has prompted more enterprising writers to brand it a form of “group therapy.” But such a designation ignores the core function of a farbrengen that indeed enables its therapeutic function: it is about spending time together in harmony and common pursuit of Chasidism’s goals.

To be sure, a farbrengen is not limited to intimate gatherings of close friends. All the Chabad Rebbes regularly led farbrengens with hundreds of their followers; the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s farbrengens, with thousands of Chasidim present, would occasionally be beamed to televisions across the globe. These farbrengens may not have had the same closeness and free exchange as “private” farbrengens, but they share the same crucial feature: verbringen, time spent, together as brothers and sisters of one Father.

Be the first to write a comment.