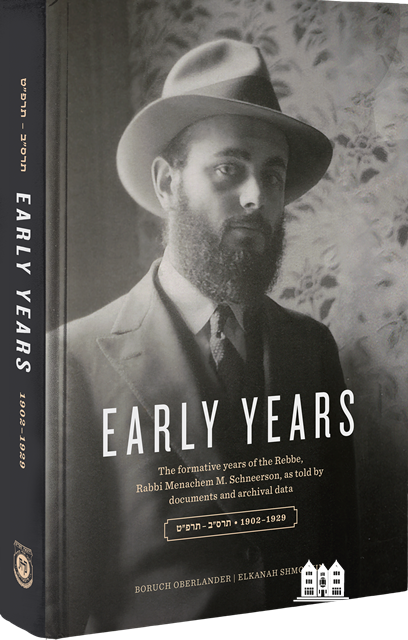

Early Years: The Formative Years of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson

Boruch Oberlander & Elkanah Shmotkin

564 pages

Kehot Publication Society & Jewish Educational Media

Genealogy is a popular hobby. Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of people who are fascinated by genealogy. The first kind of person is motivated by the challenge of completeness, of documenting facts and filling gaps. It often takes ingenuity to figure out how to find a particular piece of information—and to ascertain that it is true.

Based on the introduction to the book, compilers Boruch Oberlander and Elkanah Shmotkin fall squarely in this camp: “What was the Rebbe’s childhood like? Who were his contemporaries? What kind of schooling did he receive? Who were his mentors and teachers? What role did he play in the efforts to preserve Judaism under Soviet oppression? When did he first meet his father-in-law and predecessor, how did the meeting come about, and what was the relationship between them like? What did he do during the years 1928 to 1941, when he was living in virtual anonymity in Berlin and Paris? . . . These questions and others about the Rebbe’s early life have never been answered comprehensively.” (p. vi)

Their goal was to locate every document they could find on the Rebbe’s early life, and the book contains nearly 400 reproductions of their many finds. Shmotkin and Oberlander find great satisfaction in their successes, and also frustration at the documentation that they have been unable to track down. One has the sense of a pair of eager explorers seeking to find buried treasure.

As one notes the detailed maps and photos of Nikolayev and Yekaterinoslav, marking locations of note in the Rebbe’s childhood; copies of the Rebbe’s handwritten letters to various relatives; even the listing of the Rebbe’s name as one of the children submitting the correct solution to a puzzle in a Jewish children’s magazine, one gets a sense of the vast net the authors cast in order to uncover and document as much of the Rebbe’s early life as possible.

It takes a certain kind of mind and discipline to engage in this kind of research—great patience, thoroughness, organizational ability, and attention to detail.

But there is a second kind of person likely to be fascinated by genealogy. This kind of person, frankly, finds the collection process tedious and is frustrated by the dead ends. The hook for this person is the emotional connection—for the present turns to be an echo of the past, and the ripples we see today were set into motion years ago.

I confess to being squarely in the second camp. I blipped through most of the hand-written reproductions of letters (whose text appears within the body of the book itself). I glanced only briefly at the copies of official documents. Those of us who would not voluntarily spend a sunny afternoon sifting through crumbling pieces of paper in a dusty library will find it challenging to sift through the “raw data” of this book of more than 500 pages.

And yet, so often when I was ready to put the book down, I encountered a treasure that made it all worthwhile.

After a parent or grandparent has passed on, many of us have the experience of regretting all the things we never asked them. While they were alive, there was never the right time, the right moment. Often, we had never even thought to ask the question. And then, we encounter an old friend who shares an anecdote, or we find a diary that gives us a new perspective into the past. If we are fortunate, we find a new closeness, a new depth to the relationship, despite the fact that we thought we had reached the end of a “chapter.”

Growing up in Crown Heights in the 70s and early 80s, the Rebbe was a figure that loomed larger than life for my generation. We were constantly swept into the excitement of the moment, the farbrengens, the regular launch of new mitzvah campaigns, Shabbat and holidays with the Rebbe. I don’t think there was time to think of the Rebbe as a child, as a teenager, as a young adult. And as the years since the Rebbe’s passing grew, it seemed that what we did not yet know would forever remain a mystery.

Reading this account provides an opportunity to connect with the Rebbe in a very different way, and to deepen our appreciation and understanding of what he gave to us.

I was entranced when reading about the Rebbe’s parents—Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s strength of resolve and ability to win the hearts of those who initially opposed him; Rebbetzin Chana’s tireless sacrifice on behalf the Jewish refugees in Yekatrinislav.

In many ways, like the Rebbe, they loom larger than life. But excerpts from the Rebbetzin Chana’s diary, reframed in the context of the Rebbe’s early life, also give a glimpse of the warmth and closeness of the family.

In this context, I found the account of the Rebbe’s mother asking her sister-in-law, Rebbetzin Rachel Schneerson, to send her a copy of the pre-upsherenish photo of her son, surprisingly moving:

“I have a request, if it’s not too difficult. Make a copy of the picture you have of my son at three years old and send it to me, because I don’t have even one photo.” (p. 24).

Likewise, her account of the last Simchat Torah before the Rebbe left home:

“No one besides my husband and I was aware that he was about to set out on his long journey. That Simchat Torah, we spent so much time together, dancing constantly. In order to hide our true feelings that holiday, we tried with all our might to be more joyous and cheerful than usual. There was a Kotzker Chasid on our city at that time. He danced joyfully, singing a song which burned us like a salt on a wound. As he sang, we each tried to hide our pain from one another: ‘Yankel sets out on a long journey. On a long journey, without a penny. Yankel returns home from his long journey with full pockets!’

That Simchat Torah, our son danced in the same circle as that Kotzker Chasid many times. Each time my son danced past the place I was standing, he looked at me with eyes that told me how pained he was that he had to leave us. But they were also telling me, “Mother, don’t worry.” (p. 213)

As an educator, I was fascinated by the collection of statements gleaned from the many sichos (talks) in which the Rebbe recounts cheder memories. In the original context of the talks in which they were mentioned, these memories were an “aside”—but taken together, they offer an authentic slice of cheder life . . . and the Rebbe’s childhood perspective, a time when one attempts to make sense of the world despite limited experience: . . . “I studied Talmud Tractate Kiddushin before I had ever seen a bear, and I assumed that when I would see one it would look exactly as the Talmud describes it . . .”(p. 80)

It is tempting to think of the value of this book as the ultimate historical documentation of the Rebbe’s early years. But in fact, it contributes something far greater to the corpus of publications about the Rebbe’s life. Readers of this book are sure to encounter some new facts about the Rebbe; but more importantly, in these primary source documents, they will likely find some new points of connection.

Be the first to write a comment.