Rabbi Dov Drizin never imagined that his Chabad House would become the centerpiece of a federal lawsuit. Arriving in suburban Pascack Valley, New Jersey, in 2000, he and his wife, Hindy, found “an incredibly welcoming and gracious community” that was very receptive to the social and spiritual vitality Chabad would introduce.

The Drizins invited locals to study and pray in their home, situated on more than an acre of land, bordering the Garden State Parkway. They introduced educational programs for children and adults, outreach services for the elderly, and a host of other activities, which offered Woodcliff Lake residents—40 percent of whom are Jewish—a richer Jewish experience.

Before the Drizins arrived, Jeffrey Eilender, an attorney, became disaffected by his synagogue experience and stopped participating. But when Chabad came to town, he made his way to services, bringing his daughter Alexandra, who has developmental disabilities. To his delight, Rabbi Yossi Orenstein, director of youth activities at Valley Chabad, invited her to join their group. “Alexandra had no friends. So Chabad means so much to us,” says Eilender.

Laura A. Klein, a breast surgical oncologist and medical director of the Valley Hospital Breast Center, reports that on Sunday mornings, her three children, ages twelve, ten and eight, wake up and get dressed faster than they do on any other morning. That’s because the Chabad Hebrew school meets on Sunday mornings.

By 2006, Valley Chabad had grown from a handful of children at Hebrew school and a small group of adults at Shabbat services to a thriving community. Like Eilender, Klein, and their respective children, many Jewish people in the immediate and wider Pascack Valley area found a spiritual home at Valley Chabad. In fact, people of all faiths were touched by Valley Chabad.

Peter Molyneux, an Irish Catholic neighbor, got to know Rabbi Drizin and spent time at Chabad. Several years later, when Peter learned that the Drizens were searching for larger facilities, he was thrilled to offer them his property at Galaxy Gardens, a local landscaping center.

The terms were agreed upon and Valley Chabad felt they’d finally found their place.

But it was not to be.

Rabbi Dov Drizin with community members at Chabad of Woodcliff Lake

Rabbi Dov Drizin with community members at Chabad of Woodcliff Lake

Three Strikes, Still Not Out

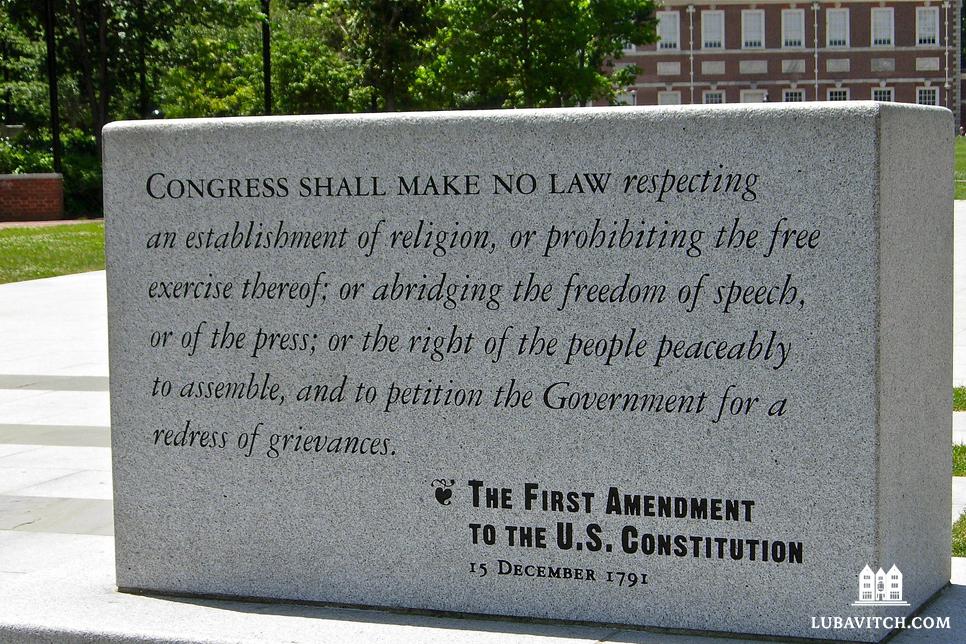

“It saddens us,” says Rabbi Drizin, “that we have a situation here that would prompt a federal case.” In The United States of America vs. Borough of Woodcliff Lake and Woodcliff Lake Zoning Board of Adjustment, the government is suing the town zoning board for violating Valley Chabad’s civil rights by denying its repeated attempts to acquire a site for its religious activities.

Ironically, observes Drizin, it was the town that urged Chabad to find a more suitable location in the first place. As the growth of Valley Chabad’s Hebrew School, adult education, and other social activities brought a steady stream of locals to the Drizin’s home, the town began pressuring Chabad to relocate a more suitable property.

When attendance at High Holiday services swelled, Valley Chabad took to renting spaces in hotels that could accommodate its numbers. But relocating for services and bar mitzvahs meant moving the Torah scrolls, prayer books, and other equipment each time. It was an expensive, cumbersome ordeal. Plus, all that instability was deterring prospective participants. Clearly, the time had come to move.

The first property identified that fit the zoning code was a picturesque site on a main thoroughfare in Woodcliff Lake, adjacent to tennis courts and a ballfield. After Valley Chabad was already in contract, the town government intervened: they said that they they wanted to acquire that particular property in order to extend their recreational facilities. Woodcliff Lake exercised its eminent domain rights and expropriated the private property for public use. To date, they’ve done nothing with it. The property, now owned by the town, sits undeveloped and unused.

Valley Chabad went into contract on another property. When the town became aware of Chabad’s intent to buy the property, they objected, saying that they wanted tax ratable townhouses to be built there. The town met privately with a developer who sought to acquire the property for townhome development, and then passed an ordinance creating an overlay zone permitting townhomes to be constructed there. At this point, the owner terminated his contract with Chabad.

In 2011, after getting the green light from town officials, Valley Chabad went to contract on a third property next door to a church: Galaxy Gardens. Rabbi Drizin established a good rapport with the priest, who welcomed the idea of having a synagogue nearby and spoke warmly to his congregation about Valley Chabad becoming a neighbor. But in short order, Chabad once again found itself barred from completing the purchase.

Detractors of Valley Chabad’s expansion often alarm residents with visions of a highly developed enclave, pointing to the large observant Jewish communities in nearby Rockland County, NY, and Lakewood, NJ. They launched a website, promoting Jewish stereotypes with the misleading headline, “Jewish Regional Hub in Woodcliff Lake.”

The hostility hurt.

Kenneth Pasternak, a financial executive and entrepreneur, has supported Valley Chabad since its inception (see interview). The son of Holocaust survivors, he is not coy about calling out the problem as he sees it. “To obstruct what Valley Chabad wants to do programmatically is anti-Semitism,” he says. “Chabad doesn’t judge. It has created meaningful interactions and provided the community with resources and assets it was lacking.”

Eilender says he is embarrassed by the turn of events. “The Jewish community here should be grateful for the services Chabad brings. I cannot believe this is happening in the twenty-first century.”

The newly-elected mayor invoked eminent domain and took the Galaxy Gardens property to be developed as park land for the town.

Boys enjoy a youth program at Chabad of Woodcliff Lake, NJ.

Boys enjoy a youth program at Chabad of Woodcliff Lake, NJ.

You Can Go Home Again

In baseball, you’re out after three strikes. But Valley Chabad wasn’t giving up. “This is our home,” Drizin says. “We are not outsiders.” So after eight years and three rejected attempts, he decided to “go home.” He began working with an architect to see if his family’s home could be adapted to expand their activities.

Valley Chabad spent two years tweaking architectural plans that would comply with the town’s relentless requests for modifications. Over the course of eighteen meetings, Valley Chabad reduced the size of the planned structure from 20,000 sq. ft. to 13,000, and continued to make compromises in an effort to gain approval.

The only Woodcliff Lake resident who actually lives adjacent to the Valley Chabad property, the owner of a horse farm immediately to the south, had no objection to Valley Chabad’s proposed construction or to the proposed retaining wall that would border his property. “In fact,” says Drizin, “he has been very supportive of our plans to enlarge.”

Home Base

Nevertheless, in August 2016, the zoning board unanimously voted to deny Valley Chabad’s variance application. It cited aesthetic concerns, the adverse impact on the “residential character of the neighborhood,” and safety issues that, according to the Justice Department, were undermined by the testimony of the zoning board’s experts

“Because there are no compliant lots available for this use, they need a variance, which takes years and years,” said Valley Chabad’s attorney, Roman Storzer. “It’s a terrible process to put a religious organization through. Valley Chabad was denied for reasons that don’t hold any water.”

Finally, seeing that they had no recourse, Valley Chabad resorted to legal means to achieve their goals, suing the town in a federal court. Storzer brought the case to the attorney general’s office, which pursues only a select number of cases. Last year, the Justice Department began to investigate the Valley Chabad case.

In May 2018, the attorney general’s office notified the Borough of Woodcliff Lake that they had one month to settle with Valley Chabad before the government would open their own lawsuit.

“Valley Chabad has been trying for more than a decade to have a place to worship, and getting bounced from one property to another, only to be repeatedly turned away. That is extremely burdensome from a legal perspective,” said Storzer.

Valley Chabad Suit First in New Federal Initiative Promoting Freedom of Worship

The town did not agree to settle with Chabad. In June, the attorney general’s office called Rabbi Drizin with the news that the Justice Department had filed a lawsuit to win Valley Chabad the right to enlarge its facility and better serve its community: The United States of America v. Borough of Woodcliff Lake and Woodcliff Lake Zoning Board of Adjustment. This lawsuit was the first under a newly announced “Place of Worship Initiative.” Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions introduced the initiative this past June in order to protect existing rules on zoning discrimination against religious organizations. He said the Place to Worship Initiative will raise awareness of RLUIPA, the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, which was created in 2000 to “protect individuals, houses of worship, and other religious institutions from discrimination in zoning and landmarking laws.”

The seventy-two-page federal lawsuit marks the latest and possibly final chapter in a lengthy saga for Valley Chabad that began in 2006. The Justice Department alleges that, “the defendants imposed a substantial burden on Valley Chabad’s religious freedom by repeatedly meddling in its attempts to purchase property in the area over an eight-year period and by citing subjective and misleading reasons to justify denying its zoning application.”

The case has implications for other religious assemblies besides Chabad. The suit alleges that the town’s land use regulations effectively preclude and unreasonably limit any new house of worship in the locale. “Such regulations also treat various nonreligious assembly and institutional land uses more favorably than houses of worship in violation of constitutional and statutory protections of religious exercise,” the suit says.

Women pose during a Mega Challa Bake at Chabad of Woodcliff Lake, NJ

Women pose during a Mega Challa Bake at Chabad of Woodcliff Lake, NJ

A Valuable Community Asset

Dr. Mikey Golub, a recent graduate of Tufts University Dental School with a specialty in orthodontics, travels to poor communities around the world to volunteer his services. He says he learned this deep sense of civic responsibility as a teenager, when he signed up to make weekly visits to autistic children with Valley Chabad Friendship Circle.

“My experience at Friendship Circle made such an impact on me that now I am involved in efforts to provide dental care in impoverished communities around the world,” he says. “I first learned about civic engagement at Valley Chabad Friendship Circle.” The orthodontist will be returning to Woodcliff Lake when he completes his residency.

That’s the kind of inspiration that Valley Chabad works to bring to Woodcliff Lake, and the rabbi laments that this property ordeal has deprived his community of time and resources that could have been dedicated to that work. “I am very grateful the Justice Department has taken on this cause on our behalf and for the benefit of all houses of worship,” he says. “We hope to come to a quick and amicable resolution and continue our good work serving this community with educational outreach for people from all walks of life.”

Speaking frankly of the opposition to Valley Chabad’s expansion, Pasternak said, “There is an unwarranted fear that expanding Chabad will dramatically change the nature of the community, whereas in realty, 99 percent of participants just want a Jewish experience. To fully engage the community and provide these programs, they need the real estate. It’s a pathway to greatest engagement.”

Eilender concurs: “Valley Chabad adds to the community; it doesn’t supplant. Chabad has improved the quality of my Jewish life and life generally in the Pascack Valley.”

Pointing to nearby communities that have comfortable facilities for their Chabad centers, Dr. Klein is emphatic about the need for Valley Chabad to establish its own community center. “Rabbi Dov and Hindy have been my guiding light,” she says. “Their community outreach extends far beyond the families in the Hebrew School or the people who attend Shabbat services. They are a really valuable asset to our community.”

Be the first to write a comment.