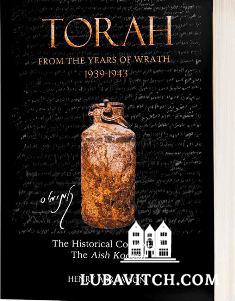

Torah From the Years of Wrath 1939-1943:

The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh

By Dr. Henry Abramson

CreateSpace, 2017

Reviewed by Chana Silberstein PhD

By virtue of the circumstances of its survival, one feels morally compelled to read the work of the Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapiro, more popularly known by the title of his book, Aish Kodesh (Holy Fire). Written in the Warsaw Ghetto from 1939-1943 under unspeakably harsh circumstances, the manuscript was part of a buried archive of Hebrew, Yiddish, and Polish writings intended to document the suffering of those years. The cache was discovered in December, 1950 by a Polish construction worker who, while clearing the rubble of war, unearthed two metal milk cans sunk in the foundation of a house. Rabbi Kalonymus Shapiro’s writings included a note asking the finder of his manuscript to bring it to publication. We, the readers, then, are the fulfillment of a mission that drove him through those terrible years: the desire to ensure that his insights in Torah would endure and speak to future generations.

We live in an age in which faith is approached critically, as if it were a scientific equation to be proved and demonstrated—as if logic were its measuring stick and argument could brace it and make it stronger. It is not that faith contradicts logic so much as that the critical, distant objective ruler of logic is the wrong tool for the job—like using the speedometer to gauge whether your car’s engine is overheating.

Faith is not an argument. It is a conversation, in which we listen, accept the premises of the interaction, make active choices and contributions, shift our direction as necessary based on the cues we hear, and most importantly, keep the conversation alive and active, in an attempt to achieve a “synergy”—a kind of “group mind” in which we are one with our Partner. Abramson’s work allows us to eavesdrop on one of the most powerful conversations of faith ever recorded.

“How can I recite the kaddish prayer,” asked the recently orphaned three-year-old Kalonymus Kalmish, “when I clearly see my father sitting before me in his chair?” (p. 26). In many ways, this apocryphal childhood incident frames the themes of Rabbi Shapiro’s life. No matter how dramatically his life would be upended, the crucial conversations would continue.

The most well-known of Rabbi Shapiro’s works to survive is a work called The Obligation of Students. Rabbi Shapiro sees the throngs of Jewish youth who have abandoned traditional observances and directs his words directly at the pre-adolescent, offering practical advice for spiritual growth while expressing compassion and understanding for the child’s love of freedom and adventure.

This delicate balance of spiritual sensitivity coupled with humane insight is evident in his collection of weekly sermons delivered between 1939-1943, recorded and edited by Rabbi Shapiro as the war unfolded. Torah from the Years of Wrath primarily deals with this work. Abramson bases his work on a new critical transcription of the manuscript that records both Rabbi Shapiro’s initial draft of the lectures as well as his personal edits of the text. Abramson gives context and nuance to the writings of Rabbi Shapiro by analyzing the content of various sermons through the lens of concurrent historical events.

On Rosh Hashanah of 1939, as the German army camped outside Warsaw, Rabbi Shapiro addressed the feeling of fear as a sign of spiritual health, rooted in the fear of the holiness and greatness of G-d and the awareness of his proximity:

“A parable: A prince is held captive among wanton people who torment him, when suddenly he senses that the king is close by. He begins to shriek bitterly, save me, my father! Save me, my king!” He cries because he senses that the king is near . . .” (p. 75)

Less than two weeks later, in the bombing shortly after Yom Kippur of 1939, Rabbi Shapiro lost his only son, his daughter-in-law, and a sister-in-law. He writes, more than a month later, during the week of Parashat Chayei Sarah:

“A covenant is made with salt, and a covenant is made with afflictions. Just as salt makes meat palatable, so too, afflictions purify the individual of sin. [But] just as one cannot derive pleasure from meat that has been excessively salted, rather only if it was properly salted, so too afflictions should be meted out only in such measure that they can be tolerated and with an admixture of mercy.” (p. 80)

Rabbi Shapiro illustrates this theme by pointing to a comment of the commentator Rashi that “the death of Sarah was juxtaposed to the binding of Isaac . . . in order to advocate for us, indicating what results from excessive afflictions, Heaven forbid—her soul burst forth. Furthermore, if this was the case with the tremendously righteous Sarah . . . how much show this is so for us.”

Whereas at the beginning the war, Rabbi Shapiro sees events as an impetus to arouse the people to come closer to G-d, as the war proceeds, he no longer attempts to find explanation for the cruel events unfolding. His tone instead is one of humble resignation, yet continued closeness to G-d.

Abramson relays the great risk Shapiro takes in order to immerse in a mikvah before Yom Kippur of 5701. The year was a harsh one, marked by forced conscription of Jews for Nazi labor, horrendous food shortages, and the widespread outbreak of typhus. As 5701 draws to a close, Rabbi Shapiro writes: “Be pure with G-d . . . even if you are broken and crushed, nevertheless be pure and whole and strengthen yourself with G-d . . . for you know that G-d . . . is with you in suffering. Therefore do not search in the future to say “I do not see the end of the darkness” rather accept all with purity . . . because of this itself, your redemption will draw near.” (p. 180)

In 5702, Rabbi Shapiro seems to sense that he may not survive the war. He speaks often of the martyrdom of the Talmudist Rabbi Akiva, and tries to bolster faith by bringing to bear a historical perspective. “It is true that trials such as we are enduring now come only once every few centuries. In any case, how can they help us understand the current acts of G-d? . . .When one learns a verse, Talmud or Midrash, and hears of the suffering of Jews from earlier times, how did faith remain intact, yet nowadays faith is weakened? The people who say that trials such as these never existed in Jewish history are in error—what of the destruction of the Temple, and the fall of Betar?” (p. 211)

Yet by the end of that year, as news of the horrible extermination of the Jews in the concentration camps reaches him, Rabbi Shapiro no longer finds history a source of solace: “Only the suffering up to the end of 5702 had previously existed. The unusual suffering, the evil and grotesque murders that the wicked, twisted murderers innovated for us . . . from the end of 5702, in my opinion . . . there never was anything like them, and G-d should have mercy upon us and rescue us from their hands in the blink of an eye.” (p. 246).

Still, there are accounts of Rabbi Shapiro somehow baking matzahs for Passover of 1943 and arranging for the circumcision of a baby boy in the last months of his life.

Abramson allows us to appreciate the depth and poignancy of the rabbi’s lectures by filling in critical historical details. He traces the arc of the rabbi’s thought in a way that allows us to see how faith deepens even as the suffering defies all comprehension. Most important, Abramson resuscitates that once silenced voice, allowing it again to give solace and inspire.

Read more Book Reviews:

Studies in Rashi: From the Teachings of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem M. Schneerson

Kehot Publication Society

MyStory: Forty-one Individuals Share Their Personal Encounters With The Rebbe

Jewish Educational Media, 2017

Early Years: The Formative Years of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson

Boruch Oberlander & Elkanah Shmotkin. Kehot Publication Society & Jewish Educational Media

(Photo: American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives via JTA)

Be the first to write a comment.